Frozen In Time: A Classicist’s Portrait of Interwar Oxford

by Clementine Scott | March 29, 2022

In one of the more blatantly cliché moments of my life, I watched the 1981 TV adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s iconic Oxford interwar novel Brideshead Revisited. Notwithstanding the fact that Oxford only features in the first four episodes, it remains that for many of us, Brideshead played a part in shaping our perceptions of life at Oxford. Daisy Dunn, author, critic, and an Oxford Classics graduate (St. Hilda’s, 2005), counts herself within that number – “you think, ‘it’ll be so idyllic’” she tells me, “you think of the punting and the champagne and the parties, and I think in some ways that element is still alive.”

In her forthcoming non-fiction book, Not Far From Brideshead, Dunn recounts what she calls the ‘shadier underbelly’ of Oxford between the wars, telling the stories of those whom Waugh knew and from whom he drew his inspiration. Her book’s three protagonists, E.R. Dodds, Gilbert Murray, and Maurice Bowra are united by her and my curiously cultish degree, Classics. Dunn is still as passionate about the Oxford Classics degree as ever, and we spend several minutes at the start of the interview chatting about the minutiae of different Greats options. Notably, she expresses amusing shock when I tell her that a certain Greek literature paper is no longer compulsory.

Throughout our conversation, Dunn continues to remind me that every name printed on my reading lists had a full, varied life beyond their contributions to the field; some glimmers of personality behind the heavyweights of interwar studies in ancient literature emerge through their writing. Dodds was notoriously cantankerous in his dismissal of his undergraduates’ takes on Oedipus Rex, and Murray rendered Greek tragedy in a manner simultaneously cultured and accessible. Dunn, however, tells a much more rounded tale about them. The reputation of Dodds is one of an archetypal, strict Oxford don – the tweed and gown type – but this is rather dispelled when we understand that his ‘paradise years’, as he called them, took place during his brief sojourn teaching at the University of Birmingham, where his students included Louis MacNeice and W.H. Auden. Comparatively, Oxford was the alienating place that coercively rusticated him, an Irishman, in his final undergraduate year due to his support for the Easter Rising.

Maurice Bowra was a staple of Dunn’s tutorial reading lists when she studied at Oxford. In researching him she found that the scholarly veteran was not only Waugh’s inspiration for the obsequious Mr. Samgrass, but also an eccentric rake whose homosexuality was an open secret among his peers. Bowra’s story undermines Waugh’s seemingly progressive portrayal of Oxford’s proto-gay scene. Dunn recounts how Oxford rejected him for the position of Regius Professor of Greek – likely on account of his sexuality. The implication stood that, in a Victorian mode of morality, “being a ‘family man’ would help him be taken more seriously as an academic”. Dunn cites this as an example of the dichotomy between progressivism and tradition that existed in the 1920s, wherein “on one hand they wanted this joie de vivre which had been missing for so long, but at the same time there were all these rigorous traditions which held them back”.

“Life wasn’t that easy for everybody at university in the period,” Dunn explains, “and this goes for all kinds of different groups, especially women.” Five minutes earlier, I had been telling Dunn about an inspiring solo tutorial I’d just had on The Odyssey, but now she reminds me of the sobering fact that 1920s-me would have needed a chaperone for any one-on-one contact with male tutors, and that a quota limited the number of matriculating female students until 1927.

Nevertheless, this chapter in the history of Oxford’s Classics degree has its light-hearted moments too, and it can be comforting to remember how little the course’s idiosyncrasies have changed in the past hundred years. “From what I’ve read, I’ve seen that the texts haven’t changed. We still have to get through all of Homer and Virgil,” says Dunn in an observation which seems both reassuring and bleak in its reflection on how Classics as a discipline often seems to be frozen in time. “Their reactions [to their degree] don’t seem to be a million miles away from ours,” Dunn further reflects, as she tells me how Bowra too once went through that particularly traumatic experience of having his philosophy tutor “unpick every word in his answer that was wrong”. She leads into anecdotes about how the poet and one-time Classics undergrad Cecil Day-Lewis would “get himself worked up” and “found going to tutorials really quite difficult”. In one of the more unlikely episodes of our conversation, Dunn tells me about how Day-Lewis was initially allowed to skip Mods, the second year classicist’s rite of passage, and proceed straight to Greats, which then focussed on ancient history and philosophy. He then returned to Mods and found his passion for ancient literature.

Amongst these charmingly relatable anecdotes, however, you get the distinct feeling that perhaps not enough has changed in Classics. Dunn argues that “being tested on a solid foundation which I knew I would need” helped her “feel more secure in myself as a classicist”, and while I do in part agree with her, I also wonder whether students in any other degree would be so accepting of an introductory syllabus that has hardly changed in a century. There may well be a need to think beyond the necessity for a ‘foundation’ in Homer and Virgil. Though of great comfort to Day-Lewis, this foundation is sometimes regarded by Classics students now as an unwieldy obstacle to get over and done with before Greats.

There are yet more worrying parallels to be found between the world of Not Far From Brideshead and the Oxford student experience in the 2020s. I ask Dunn about whether the notion of Oxford as a ‘bubble’ existed in the 1920s, with (somewhat) progressive attitudes being more readily found in the city than outside of it. She responds with an all too familiar narrative of some students “remaining closed off, without taking much interest in national politics” while others would “think this is obnoxious and want to engage with the wider world”. Much of this tension between the desire to enjoy Oxford and the awareness of the world beyond the city came to a head during the General Strike in 1926, when millions walked-out in protest at proposed wage reductions for coal miners. While some students had not even heard of the strike – to the dismay of MacNiece, a student of Dodds – others, though possessing social privileges that prevented them from experiencing the material reality, protested alongside the workers in London. One Cherwell leader described the workers’ conditions as “one of the greatest travesties ever to have occurred”.

The Cherwell’s treatment of the event as a disaster of this scale can partly be attributed to the liminality of the period, caught between the tragedies of the past and tragedies yet to come. The polarisation of Oxford students sometimes seems like a microcosm of a nation on the brink — the Oxford Union famously voted in 1933 that it would not “under any circumstances fight for King and Country”. One cannot help but draw parallels with present day ‘culture war’ narratives, in the light of the intense news coverage of the debate at the time, Churchill’s designation of it as a turning point in international attitudes to the British, and the intriguing glimpse of a wavering and traumatised nation it gives to those of us with hindsight. Whether it’s a portrait of the Queen in the Magdalen MCR or societies refusing to invite certain speakers, there is still a worrying tendency for the opinions and decisions of Oxford students to be taken as some kind of Litmus test of the state of the nation. Only time will tell how historically relevant these moments will prove to be, but the unwarranted clout held by student decision-makers in Oxford on an international scale is, unfortunately, nothing new.

There are reasons to be hopeful, however. Dunn is perhaps at her most enthusiastic when discussing intellectual history and how the ideas proposed by her three protagonists reflected the times in which they lived. “Bowra’s experiences as a war veteran really informed the way he wrote about war in literature, and Gilbert Murray drew some really striking parallels between the Peloponnesian War and the First World War,” she says, since both conflicts represented a new, more splintered experience of warfare without a clear enemy. These aren’t parallels you can make without first-hand experience, and they loom large in their interpretations of ancient texts. So, too, do rather more esoteric preoccupations: Dodds not only reassessed Euripides’ Phaedra and her ‘hysteria’, traditionally dismissed by Victorian tradition, but also employed his own fascination with fashionable practices. He used hypnotism, seances, and telepathy to inform his readings of such mysterious ancient experiences as the consulting of the Pythia at Delphi in his 1951 classic, The Greeks and the Irrational. “He applied his own interests to scholarship in order to look at the ancient world in a different way,” explains Dunn.

One wonders what new lenses we can use to examine the Classics in 2022. “I wish I could produce some really ground-breaking scholarship! But maybe the new lens is the fact that we spend so much time communicating [in a way that is] not face-to-face,” postulates Dunn. We go on to discuss how the interpretation of physical space in the ancient world and the role of communication via messenger contrast with our age of increased communication and minimal long-distance travel. Like Bowra, Dodds, and Murray, we live in a time of uncertainty, stark social divides, and technology which changes how we look at the world, but perhaps intellectual historians of the future will reflect not on our worst pitfalls, but on how our ideas responded to our experiences of them. Dunn’s description of Brideshead-era Oxford may seem like a liminal, idyllic space that never really existed, but there are nevertheless lessons to be learnt. Through the examples of Bowra, Murray, and Dodds, may we remember that we are not merely scholars of the ancient world, but reflections of the unique times in which we live.∎

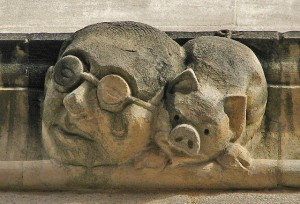

Words by Clementine Scott. Art by Natalie Hytiroglou.