Notes to Shelves

by Charlie Taylor | August 26, 2021

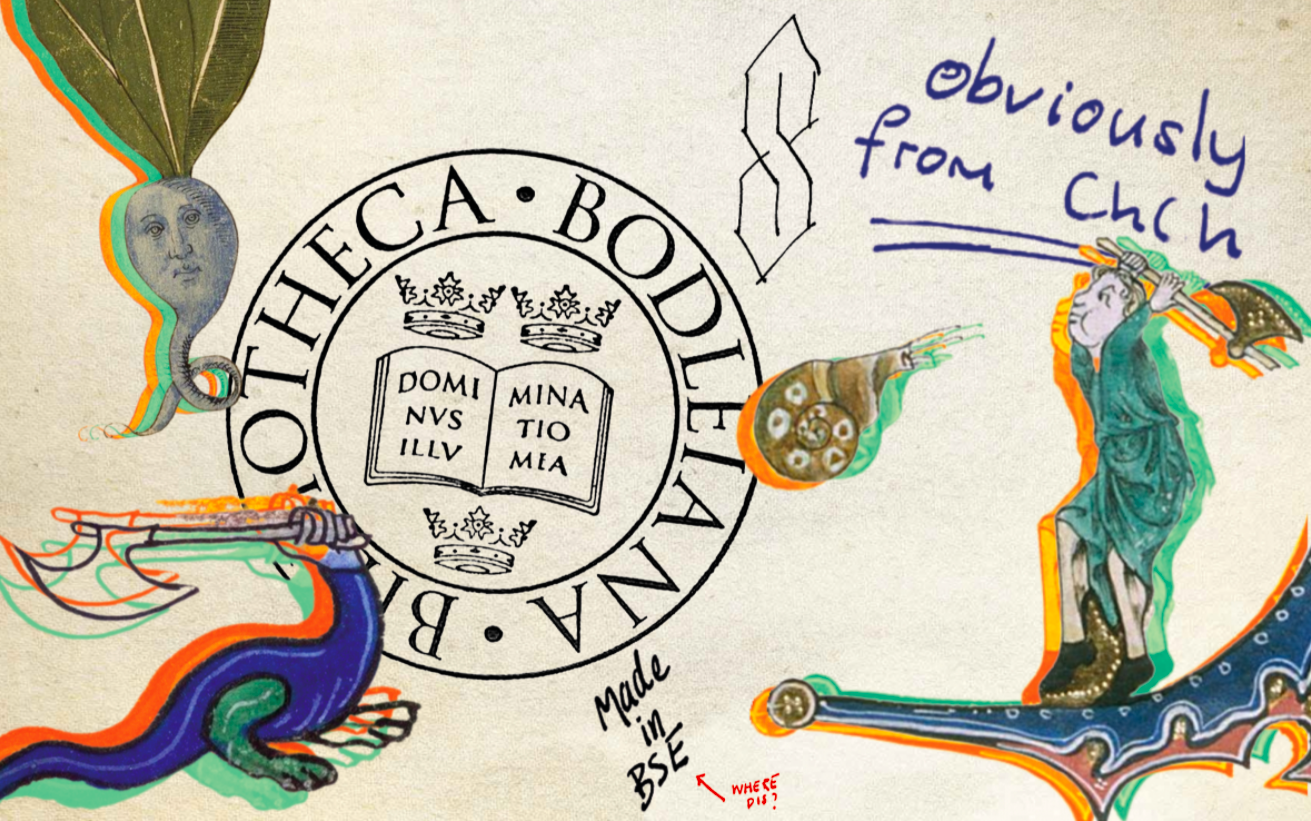

In a cold library – its silence occasionally disturbed by a lone cough or a floorboard creak – you turn over the last page of your book, only to be faced with an argument in the margins. According to one reader, the book is “shitty Marxist bollocks”, to which another has retorted “fuck you tory pigdog”. A mediator arises, telling them both to “calm down dears, its only history?”. Marginalia is by definition subversive, trying to (almost literally) provoke the reader to take notice of its imposition on pristine pages. In 1601, the Bodleian Reader’s Oath – a set of codified library rules – had to be sworn by all new readers of the Oxford University Library. A seventeenth century scholar could not under any circumstance “make erasures, deform, tear, cut, write notes in, interline, wilfully spoil, obliterate, defile” books.¹ Yet marginals cannot be held by these rules – they are the voice of an impromptu review, a lament at lengthy reading, sometimes attempting to induce a laugh, to scandalise, or more commonly, to simply procrastinate. Despite policies which ban marginals, they still thrive along the pages of books, continuing to stir their many readers.

The ‘Oxford University Marginalia’ page on Facebook, which has over 11,000 members, contains a collection of posts showing the hilarious and absurd manicules Bodleian readers have come across. In one book, the claim that Oxford academics failed to make “sufficient accommodation with the world outside the university” receives the cynical musing “what’s changed?” as well as a more appreciative “here here”. The mocking “you all so obviously went to Wadham” spells the end of the conversation. On the edges of a book critiquing Margaret Thatcher, a furious right-winger writes “yet another left-winger. Snore”. Penned in the same book using a reactive blue biro is “fuck the rich”, and further down, William Rees-Mogg is simply labelled a “twat” (and for good reason). The marginalia can range from cautionary notes on reading – “this essay is a pile of shite – don’t bother” – to the more puzzled comments: a reply to Wordsworth’s line from his 1805 Prelude “upon my right hand was a single sheep” takes the form of the taken aback “I am sorry?”. These posts contain a litany of comical absurdities, crass comments, and Oxford-centric lingo, begging the question: why is marginalia so popular?

We look in the margins because we care what other people think. Part of explaining the marginal phenomena, therefore, naturally comes down to a love of reader-response. Every instance of marginalia is somewhat unexpected, a literary heckle drawing you in and confronting you with an annotation, doodle, or grammar point. While authors provide their own form of annotation in overlooked footnotes, our eyes are usually drawn to disparate scribbling instead. George Steiner defined an intellectual as a “human being who has a pencil in his or her hand when reading a book” – the uses of marginalia can provide scope for this intellectualisation. Steiner’s definition works for some annotations: Herman Melville’s underlining of sections of Paradise Lost shows where he found inspiration in his reading of John Milton for his characterisation of Captain Ahab in Moby Dick. Marginal annotation can function like an “original comments section”, evoking the thrill of seeing exactly what someone has thought about a specific paragraph, sentence, or image.² It is an immediate response which is mediated only by the reader. In this way, marginals can become souvenirs kept over time, reasserting themselves as fragments, thoughts, pictures, sentences in a self-replicating cyclical process, a confusing maze of response to response to response, an act of provocation for the next reader, if you will.

From neat handwriting to rushed lines, the margins provide a far subtler characterisation of readers than online comments do. Billy Collins’ poem Marginalia shows how past readers personified their annotations: there are the intellectuals “raging along the border of every page” who want to grasp every part of an argument, wishing they “could just get [their] hands on you / Kierkegaard,” compared to “more modest” student voices who nervously leave their “footprints / along the shore of the page”. Collins suggests that there is more to annotation than simply defacing a library book. It’s often the personal, absurd, and subversive nature of marginals that takes center stage: Mark Twain’s own comments in an annotated copy of Melville’s book calling the work “the drooling of an idiot” seem emblematic. Whether simple underlining, brief comments (why?), or even just punctuation connoting excitement (!), or most commonly of all, confusion (?), this type of response revels in the commenter’s personality, and this subtlety is part of marginalia’s charm, constructing a lengthy paper trail between past and present readers.

Marginals as a form of provocation have existed since the beginning of the book – they were and continue to be a space for the absurd and jocund. St Boniface in the year 745 complained to his brothers that the “ornaments shaped like worms, teeming on the borders” of books speak to a “lechery, depravity, shameful deeds, and disgust for study and prayer”.³ However, the flyleaves of medieval texts saw an even grander display of the margin’s potential for provocative witticisms. In a world where paper was scarce, margins became a place for scatological poetry, oral folklore, or even draft letters. Humorous nonsense poetry called ‘fatrasies’ (meaning trash or rubbish) litter medieval manuscripts, indulging in their own ridiculousness, as one example shows:

“From the foot of a mite a fart hung himself

The better to hide behind a goblin”.⁴

The Romanesque illuminator Master Hugo, by contrast, incorporates these absurd marginals within his illustrations of the gospel of Jerome in the grand 12th century Bury Bible. The letter F, for example, becomes a centaur with a wooden leg shaving a hare with scissors, accompanied by fish-tailed sirens.⁵ This tradition of integrating illustration into annotation continued well into the Renaissance – in an early manuscript of Aesop’s fables (the Esopo Volgarizzato) used for teaching young scholars Latin, one finds a catalogue of such marginal drawings. These wavering illustrations include wonky castles, mice, and lions, all in faded ink, while a doodled donkey has been given a large penis and testicles. Evidently, through the incorporation of these images by both master illuminators and teenage Latin scholars, the margins become a space beyond reality where beasts, landscapes, stories, and people roam free in carnivalesque splendour down the flyleaves.

Much like in the Bodleian Facebook group, personal polemics take place on medieval pages. In a fifteenth century copy of John Hardying’s English Chronicle, an angry reader inveighs: “Henry Medlton is a shyt and lousy knav I dar bowth say and swer”. As readers, we can sympathise with poor Henry on the receiving end, with the insult made all the worse given the scarcity of writing material.⁶ From within the scriptoriums of medieval scribes come a series of complaints about their work: “the work is written master, give me a drink. Let the right hand of the scribe be free from the oppressiveness of pain”.⁷ Instead of scribes being oppressively pious, the nature of reading in cold damp circumstances with poor lighting and lack of will reassures the modern reader that their circumstances are not so different to those in previous generations. The scribe’s wish to be free from oppressive work is eerily similar to what I say to my tutor following one too many essays a term.

Marginalia’s history is a cacophony of absurdities, a provocative prodding of the solaced reader, all done through the medium of coarse handwriting and vulgar images. The popularity of the Bodleian’s marginalia group testifies to the interest we have with older readers’ responses, eager to come across pencil scribbles in old or second-hand books. In his essay Unpacking My Library, Walter Benjamin suggested that the sphere of reading itself is as much one of “images, memories” as it is of words.⁸ Marginal comments reinforce an idea of reading made up of small souvenirs, thoughts, images, and memories which make us take notice. In the middle of a library, we are temporarily taken out of our scholarly engrossment to ponder, chuckle, or look closely to decipher some small scribbles. As we gaze upon these old books and their margins, we are left thinking that not very much has changed.■

¹ Original Bodleian Library Oath

² Oxford’s Marginalia Obsession, The New Yorker 2014

³ Image on the Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art.

⁴ Ibid.

⁵ Ibid.

⁶ See Daniel_J_Daveis’ Twitter: link to a collection in the Yale Library (particular version was in Sarah Peverely’s A Good Exampell to Avoid Diane)

⁷ https://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/the-humorous-and-absurd-world-of-medieval-marginalia

⁸ The Art of Unpacking a Library, Alberto Manguel, The Paris Review, 1st February 2018

Words by Charlie Taylor. Art by Joseph Dobbyn.