Words and photographs by S. Parke.

A Love Letter to the Glaswegian Dialect

by S. Parke | March 27, 2021

“DJ Fucking Badboy here

Steamin as Shite

Am ’boot ti tell you a story

’Boot ma Friday nite…”

This is how DJ Badboy’s ‘Friday Nite’ opens – a track well-familiar to anyone who spent their teens at sweaty Glaswegian house parties. I once made the error of writing about ‘Friday Nite’ for one of my university essays, resulting in a tutorial where my highly respected Oxford professor asked me with deadpan sincerity to explain what it means to be “steamin as shite”. How was I supposed to convey the sheer culture imbued within these lines to anyone who hadn’t grown up in Glasgow? That these lines were as well-worn into the psyche of the modern Glaswegian teenager as the works of Shakespeare: to be, or not to be steamin as shite, that is the question… After I gave an abridged explanation (“It means getting wankered, Professor”), it left me thinking: how do you explain the love affair that Glaswegians have with their own dialect?

After all, it’s a dialect near unintelligible to the outsider. Urban Glasgow English (GE), characterised by a thick regional accent spoken at rapid pace, is primarily composed of slang and dialectic phrases, and is densely expletive. Particularly fond of expletive infixation, Glaswegians effortlessly cleave their lexis to insert “fuck” at every opportunity, creating words like “de-fuckin-stress”, “abso-fuckin-lutely” or “fan-fuckin-tastic”.[1] Yet, for all its incomprehensibility, GE is beloved by those who use it. There are entire books written in GE, and a Glaswegian section of Twitter where tweets are written using spelling that mirrors regional pronunciation, such as “ahm”, “baws” and “shite”. A brief foray into Glaswegian Tinder confirmed that there’s Tinder in GE as well, with a few particularly memorable bios including the lyrical: “Am the specky cunt, no looking for a relationship the now, just want ma hole” and “Who’s wantin pumped?”.[2]

In fact, much of the appeal of GE for Glaswegians is precisely just how difficult it is to understand. GE acts as a linguistic tariff on Glaswegian identity since only the privileged few who can comprehend it are able to fully participate in the inner workings of Glaswegian culture. As someone who grew up abroad but went to high school in Glasgow, I’ve experienced being both a linguistic outsider and insider. At first, GE appears to be an entirely new language rather than a dialect, with translations required for everyday objects such as a stairwell (a “close”), groceries (“messages”), graffiti (“menties”) and tobacco (“snout”). Some pieces of vernacular even have long lists of alternative translations, as I soon discovered when trying to learn the many different words that Glaswegians have for getting drunk, also known as, “getting mad wi’ it”, “muntered”, “reekin”, “rubbered”, “blootered”, “pished”, “goosed”, “oot yer tree”, “steaming”, and “ratarsed”… an impressive linguistic plethora which shines a spotlight on what Glaswegians are most passionate about.[3] Or, as my weary dad who works in Glasgow’s A&E department would drily add, one could say the same for the multiple words meaning ‘stab’.[4]

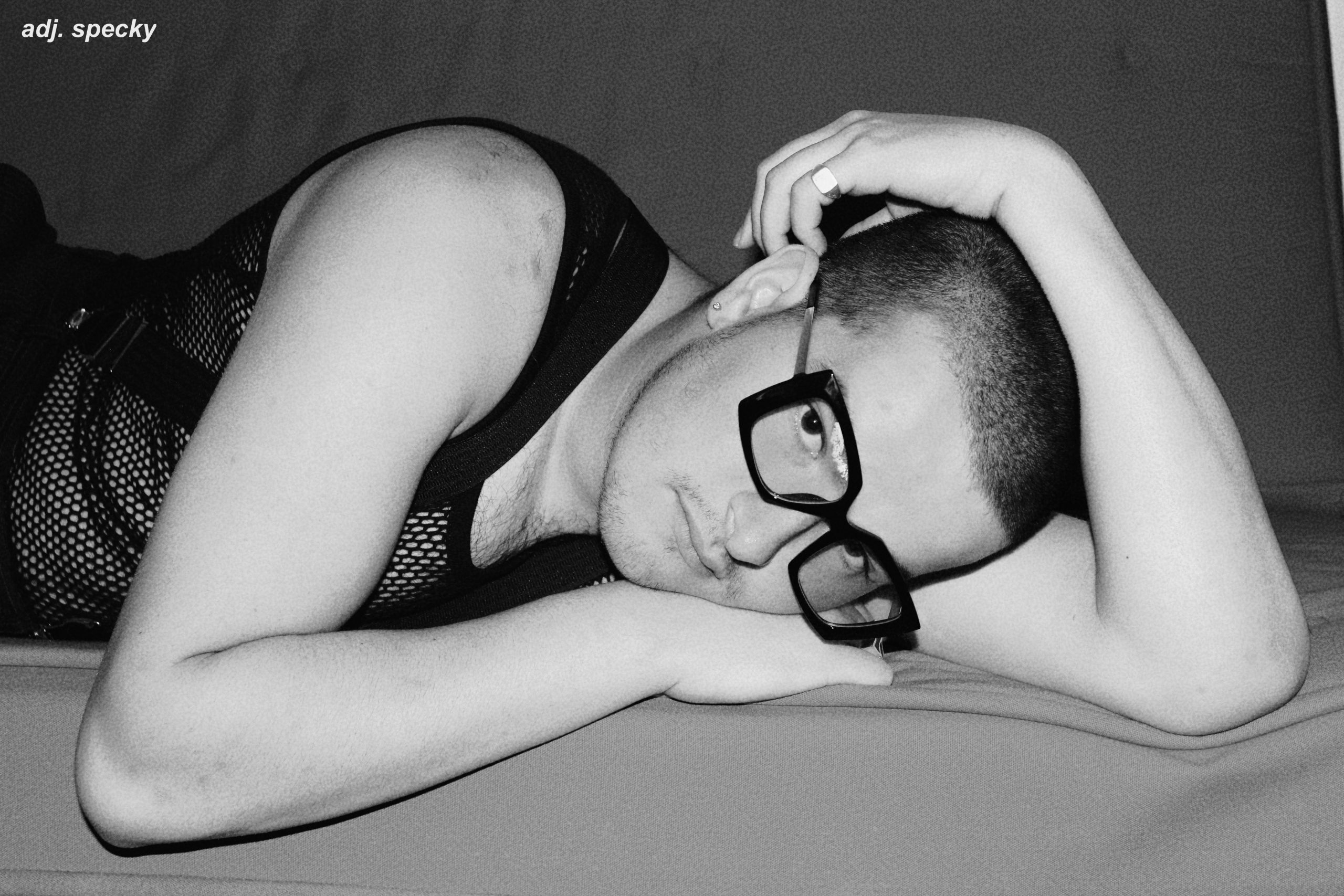

However, once you familiarise yourself with the dialect, the door to Glaswegian culture swings wide open. You enter a world of extremes, where everything is “top class” or “fucking pish”, and everyone is either “absolutely buzzing” or “totally raging”. You break situations down to their bare essentials (“Covid? Shitemare”). After memorising key chants such as “here we, here we, here we fuckin’ go”, you learn that a concert can never truly begin until thousands of you have yelled it till your voices are hoarse. You recognise cultural movements such as “Taps Aff” where one removes one’s shirt “most often in the event of warm weather” but occasionally for reasons of “simple antagonism” (as defined by Urban Dictionary). You learn about important anthropological phenomena unique to Glasgow, such as the attribution of “specky” to an individual – one of the last places in the world where it’s still considered a legitimate insult. What is more fascinating is that you don’t even have to wear glasses to be considered “specky”, as it has more to do with having a “Specky Aura” than whether you are visually impaired or not.

All jokes aside, the maintenance of GE forms an important resistance against Standard English (SE). If Glaswegians were to wake up tomorrow and begin speaking SE, we would lose so much of the culture, history, and humour that identifies Glasgow. Hang onto your local slang – it holds the key to your city. I’ve come to realise this more and more during my time at Oxford, a university renowned for its wanky old-school propriety. In protest, I find myself using more Glaswegian dialect at Oxford than I used when I actually lived in Glasgow. Full to the brim with hometown pride, it brings me great pleasure to holler down the corridors: “Let’s get steaming the night!” – albeit in a slightly Kiwi accent.

This is my love letter to the Glaswegian dialect: I love you, and when I am away, I miss your constant effing and blinding, your directness and your enthusiasm. I hope that it won’t be too long until I’m back in a grotty nightclub with my pals and hear a familiar distant rumble… it will start quietly, and then it will grow louder, and louder, until it’s unmistakeable… Here we… Here we… Here we fucking go…

[1] Expletive infixation is regarded as a part of polite conversation and is therefore appropriate for professional contexts such as school and the office, or during medical consultations and job interviews.

[2] These examples were selected as they displayed the highest degrees of sentimental value. Other Tinder bios such as ‘If you’ve got rona you can fuck off, am no wanting yer germs’ were considered somewhat less romantic.

[3] For readers interested in the means by which Glaswegians reach a ‘ratarsed’ state, one could do some research into Buckfast Tonic Wine, also known by locals as ‘Wreck The Hoose Juice’.

[4] In 2005, the W.H.O. named Glasgow the murder capital of Europe. We have since lost our title, but it would appear that we are doing our best to reclaim it.