Two Years in Service

by Ng Wei Kai | December 23, 2019

1. I met Zhipeng the first day I got to my battalion. We were bound together, both set to finish at the same time in April next year. Everybody else in the company would finish in March. Zhipeng spoke broken Mandarin and broken English. He spoke Chinese to me for a whole day before realising I couldn’t carry a conversation in it. Zhipeng was working with laser cutters on a cargo ship before he enlisted. That’s what he learned at school, the Institute of Technical Education. He would talk endlessly about his girlfriends (there were several, all slightly too young), his visits to prostitutes, his mother, his sister, his father. He bragged about how his father had supposedly killed a man. I listened and nodded. With my A-Levels and my Oxford place and my bag full of books, I hated him. I hated how uneducated he was. How simple, how crude, how unlike me. It is hard to say what I found offensive about him. It is hard to say because it is elitist in Singapore’s supposedly classless society. Mostly I found the things he did and said to be in bad taste. Taste is like class: relative, local, and slippery.

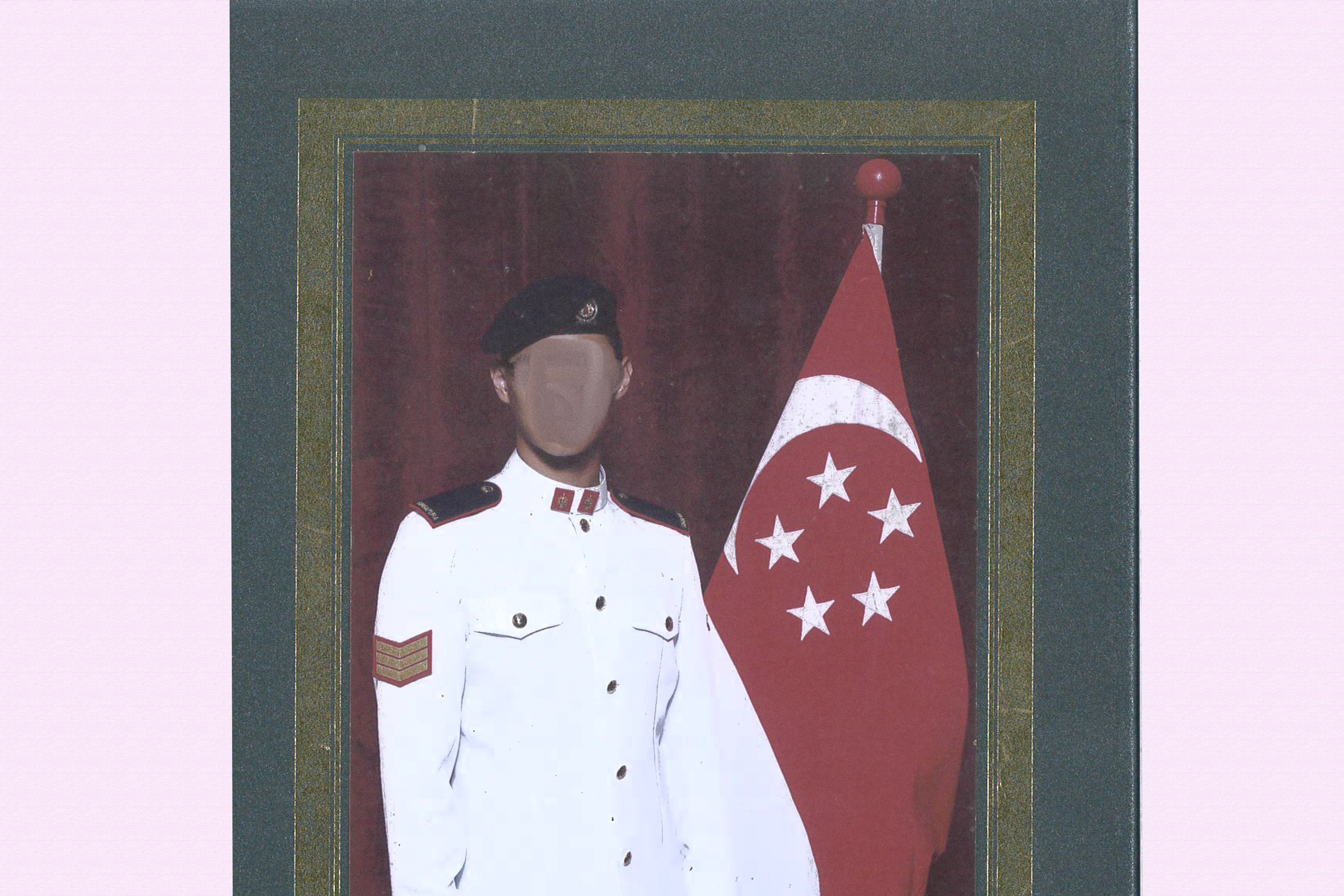

2. In Singapore, rising to the top of the military is a solid route into the political world and the ruling elite. Most of these boys are picked at eighteen, straight out of school. They are put through a rigorous selection exercise that ends with them going away all expenses paid to a prestigious university (sometimes Oxford, mostly Cambridge), then coming back and serving in the army where they quickly rise through the chain of command. Five out of nineteen of our current cabinet ministers, including the current Prime Minister, are former uniformed officers (four armed forces, one police force). So are the current heads of the national media, the trade unions, and the public transportation system. Aside from A-Level results, the selection process includes personality tests, extra-curricular achievements, and leadership displayed during Basic Military Training. They are usually groomed for these scholarships by their schools, starting at around age sixteen. I quickly discovered that I wasn’t going to be picked for one of these. These boys all seemed so efficient and organised, so industrious. And sincere. Still as I watched them troop up to teachers after classes in their cliques of neat haircuts and pressed uniforms, I felt an unshakable sense of being left out, of failing a test I didn’t know I was taking.

3. None of this was on Zhipeng’s mind when he enlisted. Born with a bad lazy eye, Zhipeng was assigned the lowest PES, or medical grade, in the army – E9L9. This meant that he was not allowed to run, jump, march, swim, carry a rifle, do push-ups, or go outfield. But he was allowed to waste his time. He spent a lot of time in a hi-vis jacket warding off cars while everybody else ran or marched on the roads around camp. He would constantly ask me if he could upgrade his medical status, or up-PES. He wanted to join in, to do the things everyone else was doing. I could never answer.

4. Once we were put on duty together. Three people are put on duty at any one time to man the battalion’s emergency phone and keys: an officer, a sergeant, and a ‘man’ (a corporal or any rank below that). The officer usually left us alone. There isn’t much to do but talk when you’re stuck inside a 2×2 metre room with no phones and no internet for 24 hours. We’d take turns to leave. At night it was just the two of us. I was lying in bed with my boots off, trying to get to sleep as early as possible to make the time pass faster. Zhipeng was talking to me about lion dance, his hobby. A ‘lion’, in southern Chinese tradition, is made of two men moving in unison underneath an ornate cloth costume. The front man has to hold and control a large, expressive, puppet-like head, with eyes that move and flash. There are usually two lions in a performance, and a large, loud band made mostly of drums and cymbals. You can hear them from miles away. There are lion dance competitions every new year, where the lions between poles are set four to five meters in the air. He would spend hours of every precious weekend out of camp practising the intricate, highly coordinated dance. He told me he loved how the head of the lion moved and showed me using a cardboard box. I never knew if he got to perform or if he was a reserve.

5. My father spent twelve years in the armed forces. He was an airplane mechanic. When he was sixteen, my grandfather signed the contract. He wasn’t allowed to sign it himself, nor did he want to. He had just done his O-Levels. He hadn’t done well enough to carry on in education or badly enough to re-take them. My father only spoke to me once about being there. The only thing he ever told me was an anecdote about a man in his camp who hadn’t gone to school and couldn’t speak any language well. Once, my father looked in a notebook the man kept, and inside he found endless scribbles of nonsense, lines and lines of nothing filling up page after page. My father used this incident over and over again as some sort of horror story, a reason for my brother and I to do well in school, to speak well, to read, for fear of becoming this man. Only years later did I realise that the fear my father felt was not born out of disgust at the man but of sameness, of recognition. He was afraid that that was how we saw him, how we thought of him. I can only imagine how alone he must have felt, how locked out and left behind within the bounds of his own life.

6. A few months before we were set to finish our service, we caught Zhipeng stealing money from one of our bunkmates. He was sent to military prison for a few weeks. When he came back, he was defiant and emboldened, proud of his new notoriety. I wouldn’t speak to him. I avoided him. I sulked for weeks. Somehow, I felt as though he had failed me, or I’d failed him. Or some messy mix of the two. We were supposed to leave at the same time. I felt like he’d left me behind. Or forced me to leave him.∎

Words and art by Ng Wei Kai.