Progress in Positano

You might claim that anti-intellectualism is on the rise. You wouldn’t be the first. The assertion that intellectualism—that is, a preference for, and emphasis on, reason and intellect—is under threat has been made many times. Let me give just one example, upon which the above statement is based. Isaac Asimov, an American writer, wrote the following in the Newsweek magazine in 1980.

‘There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that “my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge”.’

Titled ‘A Cult of Ignorance’, the article primarily criticises America’s effective illiteracy. To that end, Asimov is certainly polemical—he claims that ‘hardly anyone can read’—yet somehow his argument seems even more contentious today. That is because modernity has conflated progress with intellectualism. For example, Joel Mokyr, an economic historian, recently won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for emphasising the intellectual underpinnings which led certain parts of Europe to industrialise first.

Indeed, a certain degree of intellectualism is required to achieve progress in the technological sense. But there is no guarantee that such progress will in turn produce the conditions conducive for expanding intellectualism, although ostensibly this may appear the case. Consider one example which particularly frustrated George Orwell in Books v. Cigarettes. Developed methods of production and publishing have meant that books are cheaper now than ever, relative to people’s income. Does that mean that more people are reading? No, they simply spend the money on a plethora of alternative things that have become equally accessible. In other words, progress has made it just as easy not to read as it has made it to read. And the same is equally true of the variety of other practices which have acted as the foundations of progress in the first place.

There is a name for this pattern. A ‘progress trap’ is any phenomenon which arises out of human innovation and development but becomes a problem which is potentially impossible to combat given the limits of our capacity as a species. Such traps tend to arise from technological change and are usually of a similar nature, taking form in our inventions and environment rather than ourselves. Climate change is one such example.

But what if technology has created a different type of trap—that of human stupidity? It’s hardly out of the question: we have words like brainrot and doomscrolling for a reason. Why read an entire book when you can just ask ChatGPT to summarise it for you?

In fact, ChatGPT could have written this whole article so far (and I won’t deny that it helped me in the process). But let me rebel against this trap. There is one thing I am quite sure ChatGPT wouldn’t do and that’s change the subject completely.

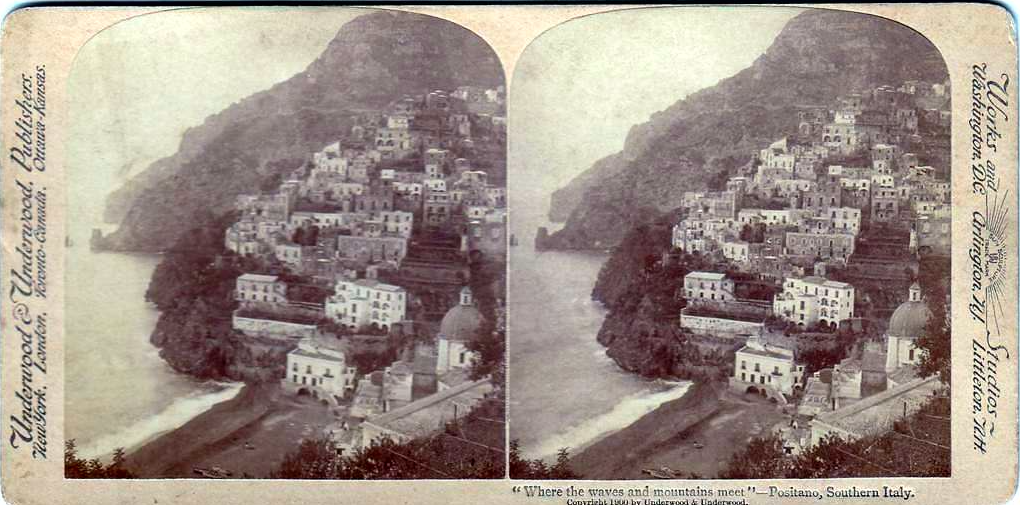

Positano is a small coastal Italian town in Campania, near Naples. My first encounter with it came in the form of John Steinbeck’s short essay of the same name. His account essentially speaks to the romanticism of the pre-modern. Here, that takes the form of the ‘unspoiled’ or ‘undiscovered’ location, even if Positano has been a holiday destination since the time of the Roman empire. In Steinbeck’s description the idyllic setting is particularly conducive to writing: ‘Nothing in the little town is designed to disturb your thoughts provided you have a thought.’

This highlights, I think, one dilemma. Today’s world is one designed to prevent the very conditions for, basically, reading, writing and thinking clearly—quietude, a slow pace, clarity of mind—as algorithms compete for our attention. How can intellectualism, or any movement which brought about this modernity in the first place, emerge from such an environment?

Tellingly, Steinbeck was put onto Positano by Alberto Moravia, an Italian novelist and avid critic of many things, including modernity. For Moravia, the modern world is defined by irony and self-consciousness, hence it is entirely absent of authenticity. His characters are often empty, devoid of the desire to think for themselves; their intellectual inertia is a defence mechanism for a world in which so much changes so quickly.

And yet that is exactly what Steinbeck loves about Positano—its characters: ‘Maybe they aren’t marketable, but Positano has them above every community I have ever seen. There are the men who have lived in America and have come again to bask in the moral, physical, political and sartorial freedoms which flourish in their birth town.’

Steinbeck’s characters are fishermen, shoemakers, carpenters and truck drivers. How many of them could read? How many could be described as ‘intellectual’? Probably no more than a few. I wonder what Orwell or Asimov would do. Throw books at them all while sidestepping the various other features of modernity? Impossible! Instead, Positano got the worst of both worlds: overrun by mass tourism, it has become neither the idyllic pre-modern nor the educated modern.

So, nine years later, Steinbeck stayed put, in America, turning a country-wide trip into his 1962 travelogue, Travels with Charley: In Search of America. But the conclusion was the same. In Part Two of the book, he reaches Washington and observes the deforestation making way for the expansion of the city.

‘The hills looked shaved, with only a few ragged tufts standing where once there had been a great and living crown of trees. […] I could see the factories and mills that had chewed up the trees, and I could understand their necessity. But it didn’t change the feeling that something precious had been taken and lost forever. I wonder why progress looks so much like destruction.’

Perhaps those trees became cheap books, shipped around the world, to Positano, where a tourist on holiday reads the words of a writer who sat in their place 50 years earlier. Enjoy the scenery they might, but look and read carefully and one thought will cross their mind: where did all the characters go?

Words by Jack Stone. Image via Jack Stone.