Secularism isn’t ready for He Jiankui

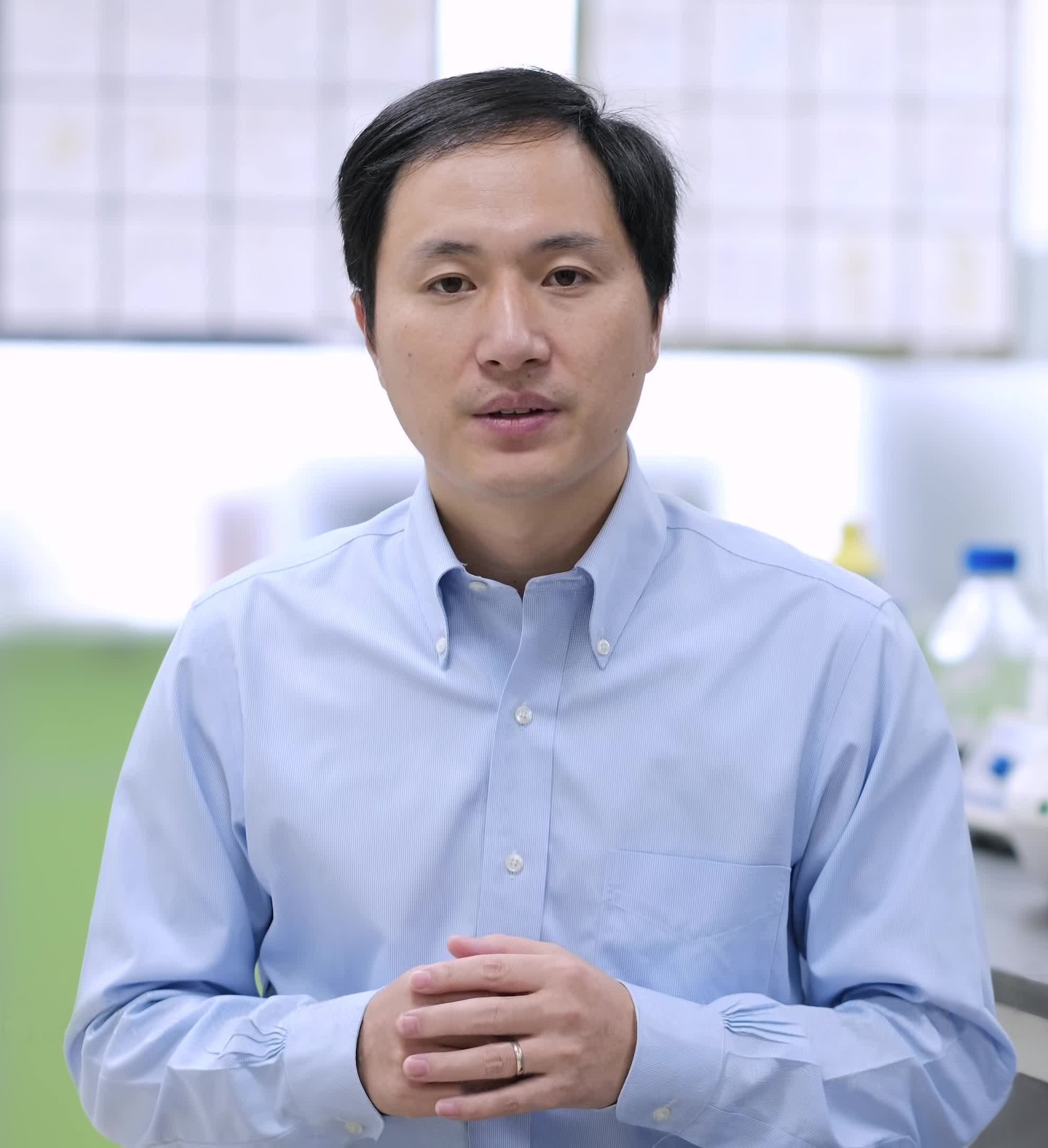

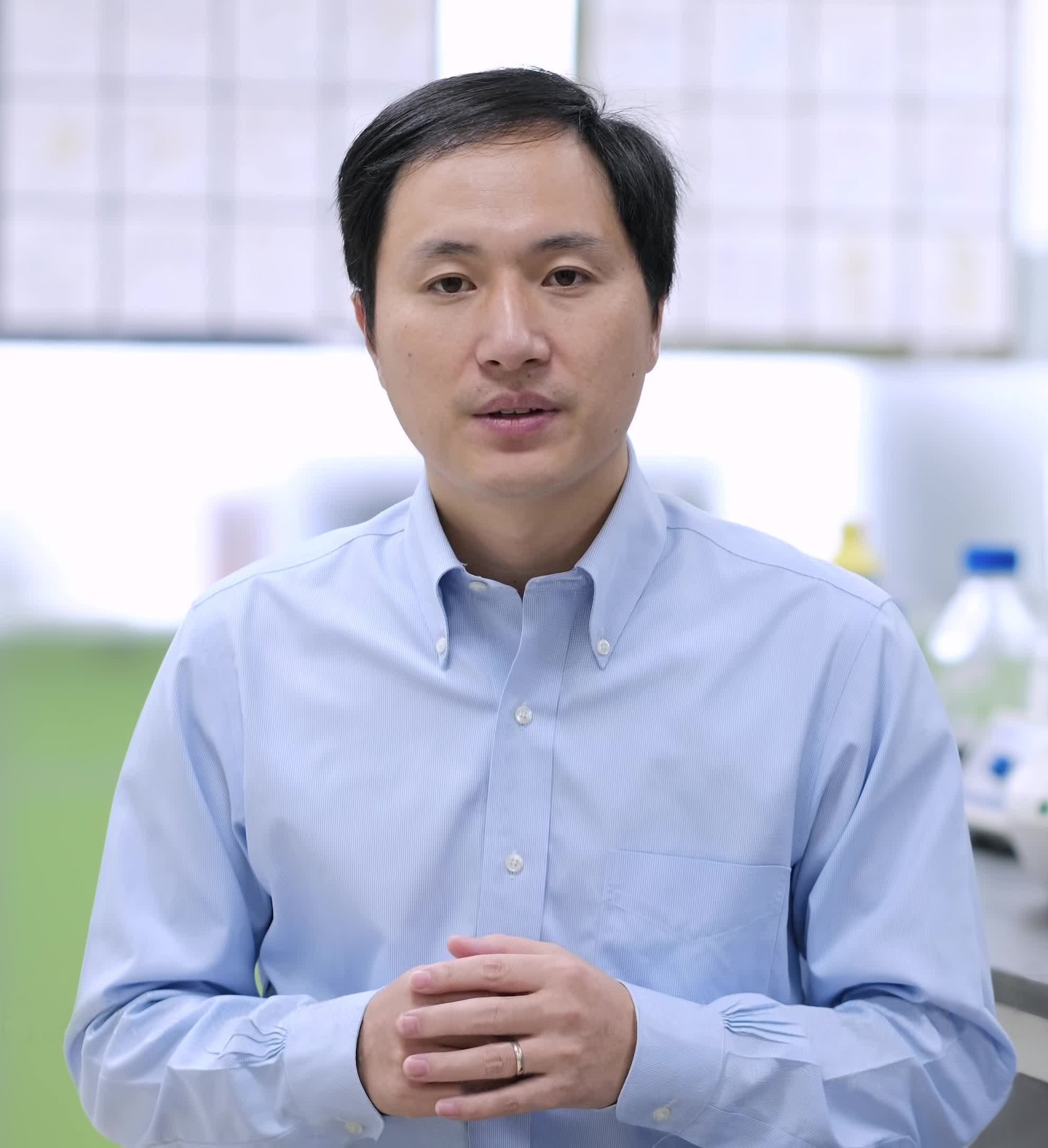

In November 2018, He Jiankui broke the mould. Two days before he was scheduled to speak at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, the MIT Technology Review announced that He had been responsible for editing the genomes of two twin girls born a few weeks prior. Although his plans to keep things secret were scuppered, he arrived in Hong Kong as the man in the arena, with the rest of the world scrambling to have their say. Nobel laureate biologist David Baltimore expressed his horror, while Kiran Musunuru called the ordeal an “ethical fiasco”. A little-known laboratory scientist a week prior, He Jiankui was soon “China’s Frankenstein” in the international press.

While “China’s Frankenstein” makes for an eye-catching headline, it misses the mark. Where Shelley’s Frankenstein experienced remorse, He Jiankui emerged defiant. A three-year prison sentence, the rebuke of the international community and the confiscation of his passport have only emboldened him. He is adamant that history will vindicate him and find him worthy of applause, proclaiming that ‘The world owes me a Nobel Prize.’ In fact, the Nobel Prize is one of two accounts he follows on Twitter (the other is his wife’s).

He Jiankui is arrogant, but arrogant in the way that enthrals. On his Twitter account, he plays part pioneer, part influencer, and part politician. Every statement has the veneer of populism, casting He as a challenger to the vested interests governing the scientific community. But for He, the Establishment he rails against is not ‘the uniparty’, nor the ‘corporate elite’; he wages war on ‘lawyers and ethicists’, unscientific bureaucrats who refuse to get out of the way. He Jiankui promotes his cryptocurrency—what’s an influencer without a memecoin—by borrowing lines from Lincoln: ‘my research is for the people, by the people, with funding from the people. $GENE’

Like the most prominent populist politician of our age, He Jiankui recognises that arrogance is the appeal. He knows that the prevailing opinion is stacked against him and so simply wants to be heard. When he compares himself to Van Gogh or tells detractors to ‘get my name out their mf mouth [sic]’, we can imagine him leading a start-up political party. He Jiankui tells us that developing resistance to HIV is ‘old news’; he has turned his attention to cancer and Alzheimer’s. But when He announces these plans, you pay more attention to him than you would any politician. He has proved his powers. Your ears prick because you know that he might just be capable of the madness he sets out to achieve.

We have not seen anything like it. Social media has granted him the unique opportunity both to share updates on his work and to market it as necessary innovation. Every statement is part of a clearly considered public relations campaign, his proselytisation are punctuated by humanising tweets in which he expresses his devotion to his wife, Cathy. He Jiankui is the first influencer scientist, and he hopes to influence a grassroots shake-up of our moral code.

Aware that his objectors have popular ethics on their side, He, like a politician, gestures at a consideration of ethics. Stern-faced in the attached photos, he tweets a variety of caveats that hover over the concerns levied at him. He states that he doesn’t want gene editing to be used for cosmetic or military purposes and is also keen to stress that the affirmative consent of potential parents is necessary. But beneath the veneer, it becomes clearer that this is lip service. Occasionally, the mask slips: ‘Relaxing ethics will help a country achieve tech dominance’, he told Twitter back in April.

For the vocal few in favour of gene editing, He Jiankui’s campaign is a boon. In He, they have a taboo breaker with a vision for scientific progress. The rest of us are forced to consider whether we have the moral armour to fight the battle that is about to ensue. A more religious age would have a simple answer—God created us all in His image—but in our more secular society, too many of us fumble around in the dark struggling madly for the words that distil why this cannot continue. All our objections, though, run headlong into the brick wall of autonomy. Having spent much of the last century emphasising personal choice, it seems strange that we stop here: why shouldn’t parents have the right to make a decision if it will improve the lives of both them and their children?

This, of course, does not prove the existence of God. Perhaps you, an atheist, have a watertight explanation for why gene editing for reproductive purposes should remain illegal. I still contend, however, that such reasoning will lack the spirit necessary to rally people against the appeal of He’s propaganda campaign. While we unravel the Gordian knot of ethics of gene editing segment by segment, He Jiankui is willing to slice straight through, flying the flag of scientific advancement as he does it.

If you’re tired of populist politicians, you’re in luck: the Internet has given us its first populist scientist. He Jiankui is rattling the guardrails of popular ethics, promising to rebuild it from the ground up. Even if the thought of designer babies on demand horrifies you, until then you can find solace in the fact that their developer is currently on twitter, sharing jokes like this:

Words by Nathan Osafo Omane. Image courtesy The He Lab via Wikimedia Commons.