Putting the fiction back in fiction

Despite the havoc that the ‘spell pharaoh’ video wreaked in 2021, in the internet age, it is impossible not to define yourself by the media you consume. Eventually everybody will find themselves on #BookTok, or [insert cursive font here] film Twitter, or one of the millions of K-Pop Facebook forums each dedicated to an idol from a group with twenty members. Regardless of where your interests lie, one thing is undeniable: we are in the end times, and you must categorise yourself. This only confirms that we will never escape the wrath of Pottermore despite all having forgotten our passwords by now.

Having had relatively unlimited access to the internet for longer than is safe or sane, I’ve ultimately settled in a miscellaneous corner, dipping into whatever rolls along the conveyor belt. Though leisure reading has become a thing of the past since starting my degree, a recent discussion on ‘book Twitter’ caught my attention. Outrage surrounding Tampa by Alissa Nutting, sparked by an account with a reading goal in their bio expressing horror at the blurb, consumed the entire community. According to the blurb, the novel focuses on a young woman who teaches at a high school and uses her position of authority to prey on fourteen-year-old boys. Not having read the book, all I can say is that I hope to see Ms. Nutting at the Unfortunate Last Names Support Group next Thursday.

I will admit, I didn’t feel the need to dig any deeper into the contents of the book to decide my stance—unequivocally, censorship is bad. Although there is no assuaging visceral discomfort, the lack of ideological repression fuelled by unease is what allows us to make the choice not to engage with something in the first place. It is only due to the lack of systemic censorship that I can choose to live in ignorance about the intricacies of Nutting’s novel. And around goes the vicious circle.

But let’s not take a completely bad faith approach. I do not doubt that the person behind the original post, as well as most of their comment-section allies, actually believes that what they’re doing is representative of their brand as The Reader. It is their duty—no, their right—as a Goodreads user with a few hundred followers to make moral judgements about what is or isn’t appropriate subject matter for literature to discuss. I know that they think what they’re doing is progressive, with their Taylor Swift/manga character/Random Girl From Pinterest profile picture, their pronouns in their location, The Song of Achilles in their favourite books list. None of these things are inherently performative—the TSOA hate train has yet to reach me—but coupled with what reads like Red Scare propaganda, it’s hard to believe they’re being genuine.

At its core, I think it has something to do with paranoia. The ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ model of reading which Freud was so jazzed about (to be fair, Freud was jazzed about a lot of things) is one that can easily be appropriated by the modern reader as a mode of virtue signalling. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick outlined it, ‘paranoid reading’ has the tendency to assume a bad surprise hidden inside everything, and often whatever they are exposing within a text is already glaringly relevant. It isn’t exactly illuminating to boo a book that discusses pedophilia by waving your finger in the air and authoritatively stating pedophilia is bad—well, yeah, obviously! Really makes you feel for Nabakov.

Online fandom spaces have never been one-size-fits-all; in every faction of book Twitter and the broader media-orientated internet space, there is invariably a ‘pro-fiction’ or ‘proshipper’ community. A proshipper is essentially someone who believes that traditionally taboo topics like incest, pedophilia, and rape should be freely discussed in fiction. The ‘ship’ within the label refers largely to slash fanfiction: by stating that you are a proshipper you are basically consenting to view content of this kind—which is aptly called ‘dark fiction’—surrounding your fandom ships. The thesis is that since there are no real bodies implicated, no real harm can come of it.

The ‘anti-censorship’ label has become synonymous with proshippers and, as a result, has been recognised by some as a dog whistle for broadly Problematic Content. Proshippers face some of the most intense vitriol out of any online community, and yet they have never been snuffed out entirely. There have been times when their opinions were especially prominent. Wincest, the colloquial name for the ship between brothers Sam and Dean Winchester from the CW show Supernatural, had an army and a navy behind them when the show was still airing. The fanfiction readership of the literal ‘bromance’ included the likes of Richard Siken and Ethel Cain. More recently, the HBO series House of the Dragon has inspired growing fascination with the incestual and pedophilic dynamics within the Targaryen family, the fanbase getting into squabbles over which uncle-nephew pairing they find more appealing.

I have to face my own cognitive dissonance, here—as long as I have been online, I have harboured some disgust towards these communities. This felt different from books like Tampa or Lolita, where it was clear the authors were using satire and deadpan as a critical device. Proshippers were celebrating depravity, revelling in it, fetishising it. This writing felt indulgent, which made me feel more just in my discomfort, in my protests against it.

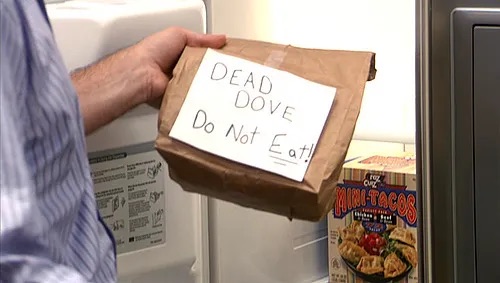

But really, I am contradicting myself. Pro-fiction communities have always been very self-contained—it’s not as if they are sending out missionaries to recruit people to their cause. Their ‘don’t like, don’t read’ motto is exemplified by a particular tag on the fanfiction site Archive Of Our Own that has been majorly co-opted by proshippers: ‘Dead Dove: Do Not Eat’. This is in reference to the scene in Arrested Development where Michael opens a paper bag with the phrase written on it, and upon discovering the dead dove, says: ‘I don’t know what I expected.’ The functionality of the tag is very simple: if an author warns you that a piece of fanfiction will have incestual content, you forfeit the right to be upset when you encounter incest in the piece. This creates an interesting tension in the discourse surrounding proshippers; the outrage surrounding these works is often sparked by blatant ignorance of the precursive red flags that the author intentionally placed there.

I don’t know if it’s useful to investigate the reason why people create this type of content. There have been many arguments made over the years, all of them having some merit. Either these people are complete degenerates, or they’re using fiction as a therapeutic tool to recover from their own trauma, or they’re taking a radical leftist stance, or the increase in pro-fiction content is a recession indicator, whatever. Maybe in an age where everyone’s getting ChatGPT to summarise their reading for them, what we have to do (to once again invoke Sedgwick) is read reparatively. Not in the traditional sense of assuming good and value in everything, but rather by accepting that something can be absolutely abhorrent and be allowed to exist nonetheless. And that you don’t have to include dead doves in your diet if they’re not your taste.

Out of curiosity, I read a review of Tampa published by The Guardian over a decade ago, around when the novel first hit the market. I’ll give you the highlights: Nutting ‘offers nothing’; the reader is ‘left entrapped in this barren psychic landscape’; the novel lacks ‘any other saving stylistic or satirical grace’. Yikes. Another justified skip, then.∎

Words by Rüya Oral.