GUILLOTINE: Modernity is inherently pornographic (Or, A Critique of ‘The Gooning Ideology’)

Figure 1. Sexy time with the cardinal…someone isn’t secluded for the conclave

Foreword – A MODEST NOTE OF APPEAL

Dear Citizen Lowenberg,

Citizen Bilsland’s ‘The Gooning Ideology’ raises interesting ideas in light of Enlightenment republican virtues. However—it misses the point. The objective of gooning is never merely a ‘masturbation so intense that it becomes a state of meditation that consumes you and provides endless pleasure’. Rather, it is a fundamentally revolutionary art form which subverts monarchies and transcends one closer to the Supreme Being—which is why I’m writing to the Committee of Public Safety to have Citizen Bilsland guillotined by Sunday afternoon.

Citizen Yang, 10 Prairial, Year 233

WARNING: This essay is jargon-free! Do not scrutinize me with words that don’t exist. Do not speak to me till I have accomplished my morning Eleusinian rite upon this piece of 10 x 10 cm mirror…in Minecraft. This essay goes all over the place but really—it is a love letter to the genre of the Situationist Dérive. Look into it if you must—it is not my responsibility to educate you.

WARNING II: Basics: Sex. Death. The Grotesque.

1. The French

Pornography is perhaps the emblem of modernity. If modernity in the Western world could be crudely defined as starting from a kind of year zero, as most papers do, it would be 1789, the French Revolution, which was arguably fuelled by, among other things, pornography.

Meet libelle, a political pamphlet that circulated in France under the Ancien Régime, which is also the origin of the modern English word libel. Near the end of the eighteenth century, the pamphlets’ attacks on the monarchy became more numerous and venomous, with the content becoming increasingly explicit, slandering the sex lives of public figures. The libelles may have also been the origin of the infamous cake quote, although according to them the baked goods weren’t the only cakes the Queen was eating (read up for Figure 1).

The most famous victim of libelle was probably Marie Antoinette, depicted as a bisexual demon constantly having drunken orgies and sexually manipulating everyone around her, including her children. The content of the libelles was in fact brought to her trial. Among the many actual legal charges lodged against her, the chief one was incest, an accusation the revolutionaries managed to produce by grooming and drugging Marie’s eight-year-old son.

The French Revolution might have been more QAnon, more post-truth, than one thinks. In Juliette, the great pornographic volume by the Marquis de Sade set in the Ancien Régime, the protagonist meets an incestuous 50-year-old multi-millionaire torturer who plots to provoke a genocidal famine that will wipe out half the population of France—rehashing the real-life, pre-revolutionary ‘Pacte de Famine’ conspiracy theory, which alleges that the French government orchestrated a series of famines throughout the 18th century to cull the population.

Pornography almost always has to do with the imagined Others. One of the most prominent tropes in French pornography since the 18th century has been the Debaucherous English, the imagined vestige of aristocratic libertinage which has been banished from republican lands but remains voracious on this raining rotting island, where unguillotinable desires are scapegoated onto the royalists—return of the repressed, a far more dangerous counterrevolution than that of Vendée, that might as well come in the form of a Twilight fan fiction by a bored English housewife.

Thus, it seems ahistorical to me to dismiss pornography as some kind of postmodern phenomenon, when the modern world is so clearly structured on alienated facts and the pornographic imagination—a world in which understanding pornography is crucial to understanding its essence, its fanged noumenon.

2. Gay

There is a log on Letterboxd for a documentary by American filmmaker William E. Jones called, The Fall of Communism as Seen in Gay Pornography (1998).

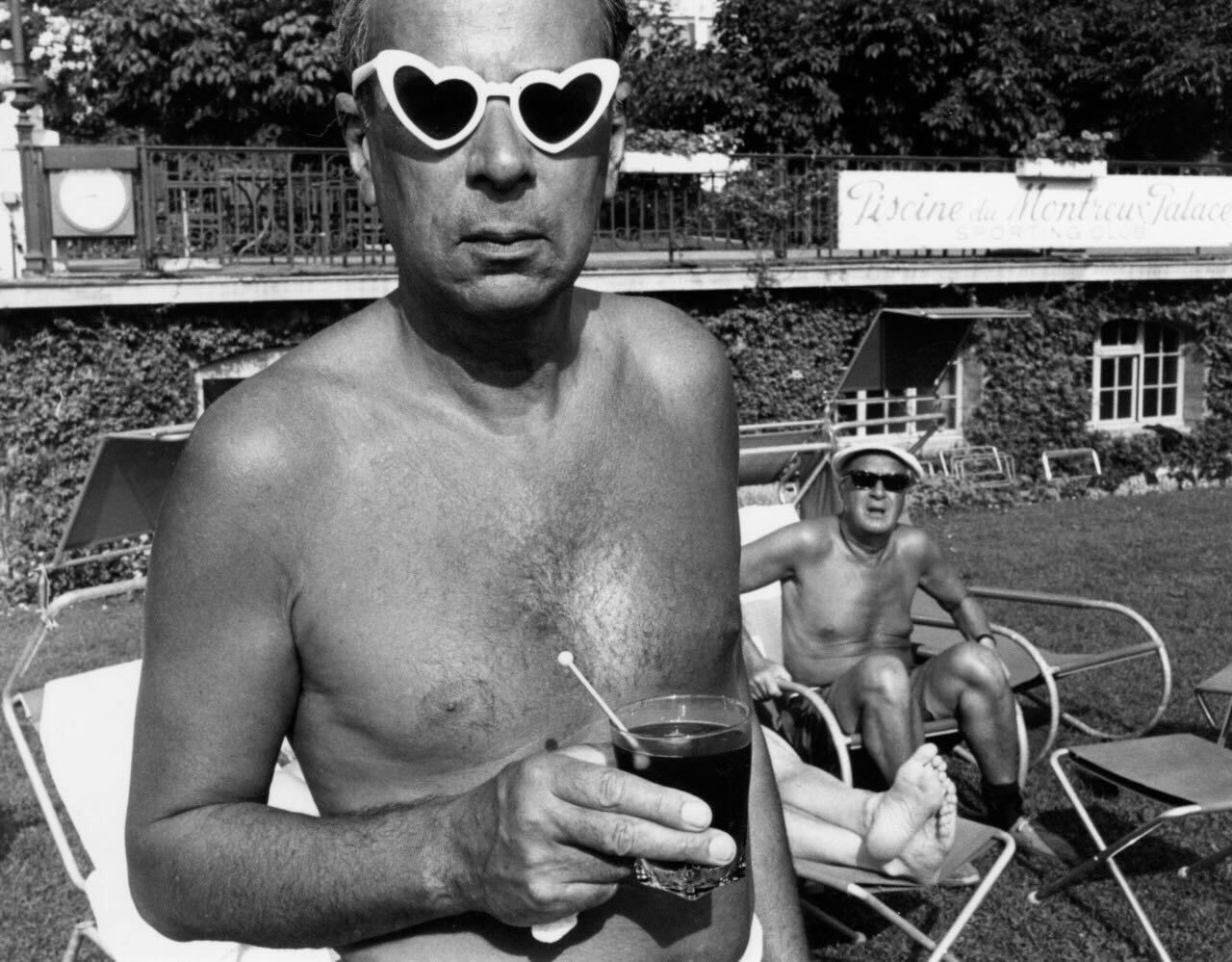

There is a really such thing as ‘a sadness only seen in Eastern European gay porn.’ And this is perhaps the porn of postmodernity, one of post-punk, the End of History, the Derridean hauntological.

Yet, at the same time it seems limiting to apply a strictly historicist reading on, say, Czech Hunter, when its sadness is universally felt, in the same way that the sadness of Tarkovsky films is universally felt. Perplexed blondes standing before a Khruschveka, in an open field, at the crossroad of History…

Figure 2. Czech Hunter 481 Figure 3. Mirror, dir. Andrei Tarkovsky (1975)

Sadness rather than arousal is the base feeling of pornography, as it is in poetry. Pornography is not observation, but rather, abstraction.

The anonymity and interchangeability of characters in pornography contributes to this abstraction. But rather seeing it as a defect, this depersonalised experience of eros is precisely the point of arousal, in the same way the humour of comedy according to Bergson comes from the mechanisation of human characters.

Like how the humour of slapstick derives from the suspension of empathy, the arousal of pornography, in a great many cases, comes from the suspension of emotions, of greater feelings that might disrupt or detour the erotic quest.

The pornographic logic is an economic one. Everything leads to sex. Though this still doesn’t tackle what it is really about.

The sadness of pornography stems from a single truth—in the words of Susan Sontag, ‘what pornography is really about, ultimately, isn’t sex but death. I am not suggesting that every pornographic work speaks, either overtly or covertly, of death. Only works dealing with that specific and sharpest inflections of the themes of lust, “the obscene,” do.’

3. Death…

Pornography is an art form of negation. As Susan Sontag points out in her 1964 lecture ‘On Classical Pornography’, the most prominent genre of pornography is undoubtedly—parody. The timeless tropes of pornography parodies everyday life: workplace scenarios, family relationships, medical exams, school encounters. They are hollowed shells, empty stages ready for the one act and one act only. Because society—and by extension, all meaningful social interactions—do not really exist in pornography. If they are present they are to be transgressed, negated, parodied as some giant machinery of sexual debauchery. Say, in the case of De Sade’s libertine regime in Juliette or QAnon’s Deep State. Pornography, like conspiracy theory, or extremist politics, leaves one feeling empty because it reduces meanings.

Pornography is fundamentally ironic. It is a labour that exists purely in the negative, a kind of inward carving into existing surfaces. It parodies rather than creates. It is always allusive, referential. It is always open, in the sense that its surreal universe, and Sade was credited by the French Surrealists, does not operate within the confines of morality, logic, space, or time. Pornography’s thrill is dependent on a sense of openness, or in the words of Sontag, ‘pleasure depends on “perspective,” or giving oneself to a state of “open being”, open to death as well as to joy.’

As frightening as this might sound, pornography is really rather mundane. Pause and think—do we really have much to lose here? The logic of pornography has already penetrated modern society. It is its foundation. The sublime simplicity of pornography mirrors modernist ideologies—the great suspensions of disbeliefs in the quest of the metanarratives, political utopia, psychic absolutism.

A safer manifestation of the pornographic imagination in modernity could be found in the arts. The novels of Nabokov for example, especially Ada, are pornographic not for their erotic content, but rather their highly ironic, parodic, detached attitude—style. Nabokov was a known advocate of the amorality of art. Instead of didactic ‘meaning’, he focused on form. When asked about the meaning of incest in Ada, he answered, or rather parried, the question with the following words: ‘if I had used incest for the purpose of representing a possible road to happiness or misfortune, I would have been a best-selling didactician dealing in general ideas. Actually I don’t give a damn for incest one way or another. I merely like the ‘bl’ sound in siblings, bloom, blue, bliss, sable.’

Figure 4. It’s giving 2014 Tumblr.

What is often left out in conversations regarding pornography, but also radical politics, cults, wellness culture, transgressive arts, or simply put—extreme forms of consciousness, is the fact that there is a genuine human need for that. What pornography and fascism pick up is what religion left behind. In the secular modern world, the only way of reaching the Divine, that is, what is beyond the personal, seems to be either gooning or suicide, or in the case of Yukio Mishima, both.

4. The Limits of Marxist Art Criticism and Humanism

In the postscript to her piece on the Hungarian Marxist philosopher and literary critic Georg Lukács in Against Interpretations, Susan Sontag roasted your favourite Marxist culture critics: Lukács, Adorno, Walter Benjamin. You name it.

‘In their general lack of interest in avant-garde art, in the blanket indictment of contemporary styles of art and life of very different quality and import (as “alienated”, “dehumanized”, “mechanized”), they reveal themselves as little different in spirit from the great conservative critics of modernity who wrote in the 19th century such as Arnold, Ruskin, and Burckhardt. It is odd, and disquieting, that such strongly apolitical critics as Marshall McLuhan have got so much better grasp on the texture of contemporary reality.’

For example, Kafka is attacked by Lukács as a reactionary for the ‘allegorical, that is, the dehistoricized, texture of his writings.’

For the Marxist critics’ general inhospitality and obtuseness towards modern art, Sontag gives the following diagnosis:

‘What all the culture critics who descend from Hegel and Marx have been unwilling to admit is the notion of art as autonomous (not merely historically interpretable) form. And since the peculiar spirit which animates the modern movements in the arts is based on, precisely, the rediscovery of the power (including the emotional power) of the formal properties of art, these critics are poorly situated to come to sympathetic terms with modern works of art, except through their “content’’.’

The subject of Susan Sontag’s critique here—the holy alliance founded between the middle-class Marxists, the conservative Victorians, and the American sociologists or the ‘woke’ (basically the three groups that make up Oxford), to exorcise the spectre of the pornographic imagination. They are united under the banner of what we sometimes call ‘Humanism’: ‘an ideology that, for all its attractiveness when considered as a catalogue of ethical duties, has failed to comprehend in other than a dogmatic and disapproving way the texture and qualities…of contemporary society.’

This standpoint is, as Susan Sontag correctly points out in her aforementioned lecture, what Marxists have typically described as bourgeois, and is here found surprisingly abundant in Marxist critics themselves.

The thing is—without a genuine outlet or left-wing spiritual alternative for the pornographic imagination, that is, the search for the impersonal, the Other, the Divine—there is no stopping the gooning or far-right or ironic Catholic pipelines. Dasha Nekrasova’s brand of Sailor Socialism would not save us…

The militancy of 20th century Marxism has degenerated into the typing and shitposting of bourgeois intellectuals. But I am also not simply calling for the Revolution. If we have learned anything from the last century it is that a Revolution is not Revelations, that what happens the morning after the orgy of a Revolution matters just as much if not more than the Revolution itself.

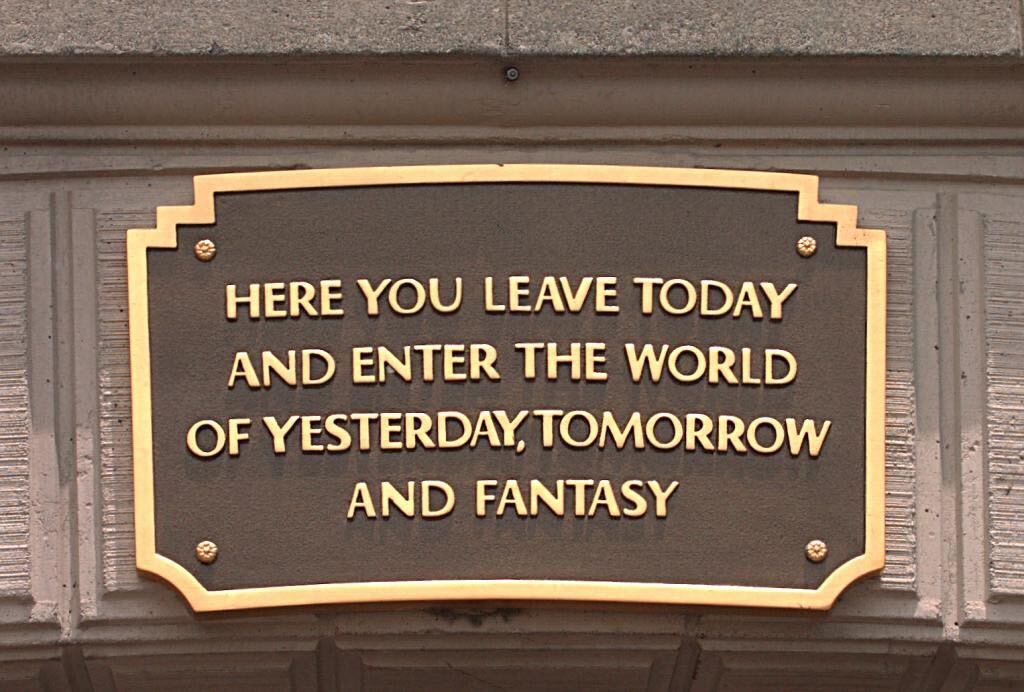

What I hope for now is simply that we all gain a more sober sense of the modern world and ourselves. Yes, there are problems, but they cannot be solved by clinging onto the past or the future or fantasy. Just so we don’t all sound like the entry plaque to Disneyland.∎

Figure 5. The Happiest Place on Earth

Words by Zac Yang. All images sourced ethically.