Blame neoliberalism for the rise of the far right—and everything else

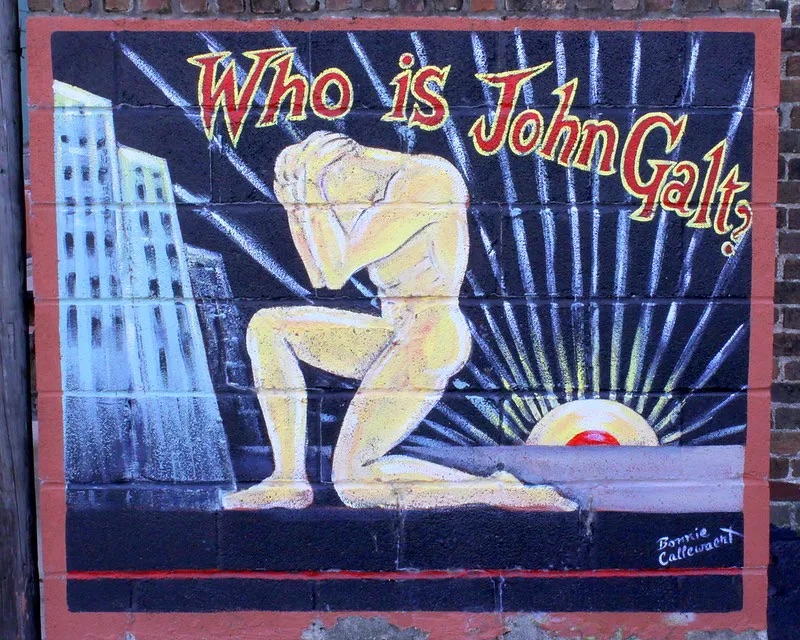

On a particularly memorable occasion, caught between reading Atlas Shrugged and going to the pub, I found myself instead scrolling through Instagram. The algorithm—god bless it—directed me to the distant world of late bourgeois society, a generic meme account with a penchant for political humour. I came across a post showing the most read articles of the Financial Times, with the number one spot occupied by a piece titled: ‘Don’t blame neoliberalism for the rise of the hard right.’ What was that, John Galt?

I scrolled through ‘latebourgeoissociety’ some more, getting a semblance of the general political views of today’s younger generation. Among the witty jabs and online references, a running theme emerged: anti-fascism. This isn’t so dissimilar to the left-wing media elsewhere—a spectre no more, so the commentators say, the authoritarian ideology is re-emerging with a new face.

Now, the Financial Times journalist who inadvertently prompted this article chose ‘hard right’ rather than fascism. So what? Others, for example, opt for ‘neo-fascist’. What’s important is the striking fluidity with which the terms are interchanged. Yet fascism is renowned for being difficult to define. One thing that is usually agreed upon is its negative character: it is anti-communism, anti-Semitism, anti-conservatism, and so on. But in the 21st century, the far-right is also pro-Zionism, anti-immigration, and—in the case of neo-fascism—anti-neoliberalism. Suddenly there are anti-definitions of anti-definitions; one could be forgiven for thinking that such public debates are obscured intentionally.

And wasn’t ‘latebourgeoissociety’ suggesting that neoliberalism enabled the rise of fascism? Certainly, the ideology is the target of much contemporary criticism, and unlike fascism it is relatively easy to define. A dictionary will tell you that neoliberalism is characterised by its economic principles—not just the classical faith in the free market, but also a perverse obsession with an imaginary world in which human beings, oh-so rational, try to maximise everything (apparently such a world doesn’t just exist in Ayn Rand’s head). Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan—the power couple who spearheaded the rise of the neoliberal agenda in the 1980s—personified such ‘agents’. Their coming to power resulted from a loss of faith in the post-war Keynesian consensus, which aimed to minimise unemployment and improve social welfare through government spending.

Ever since, the principles of deregulation and thrifty spending have increasingly dominated the policies of governments across the West. What was new in the 1980s has become the status quo; the neoliberal doctrine has spread its wings. Consequently, faced with Russian aggression and American semi-isolationism, Europe has turned to military Keynesianism. Follow the divinely ordained ‘fiscal rules’, so the idea goes, no matter how much austerity it requires, except when it comes to funding the military-industrial complex, then you can be a good free-spending Keynesian all you like. What, for example, could have motivated Germany to finally scrap its debt brake? The need to invest in the long-neglected social infrastructure in the east, where the extremist Alternative for Germany (AfD) dominates politically, or the Trump administration’s rhetoric of a European rearmament? The latter, apparently. The result: the far-right is more rampant now than at any point since the Second World War. ‘Latebourgeoissociety’ captures the insanity of this new reality with a caustic photograph of policemen defensively guarding a Tesla office.

The police image alludes to another grievance of today’s younger generation: the inability to protest. That a recent article in The Economist alleged that Europe is ‘the actual land of the free now’ resembles the kind of irony worthy of a post on ‘latebourgeoissociety’. Perhaps the laissez-faire magazine should reconsider what exactly it thinks is free about restricting the right to protest climate inaction or genocide. Keynesianism, it turns out, is not the only thing to have been militarised. As with its economic underpinnings, neoliberalism’s affection for police repression can be traced back to the Thatcher era. Increasing legal crackdowns on protests are eerily reminiscent of the ex-prime minister’s radical mobilisation of the police against rioters. Today, the sheer absurdity of Holocaust survivors being questioned by the police for voicing their opposition to Israel is too difficult even for ‘latebourgeoissociety’ to capture.

With diminishing room on the street, politics move online. But here, too, the left is just as vulnerable to the same corporate elites whose interests are served by the neoliberal agenda. It is no surprise that Trump’s power politics have centred on courting the tech CEOs; their fixation on ‘free speech’—whilst censoring pro-Palestinian content—encapsulates the contradictions of a political establishment wedded to neoliberal orthodoxy.

Austere, militant, and repressive—what exactly is liberal about neoliberalism? The name certainly is misleading. By adopting an older (and more defensible) ideology and tagging a ‘neo’ on the front, the new doctrine has supposedly become the logical continuation of its predecessor, acquiring a particular legitimacy in the process. Neoliberalism has done this so effectively that it no longer renders a dash between neo and liberal necessary—it is its own definable phenomenon, convenienced by its relationship to a more open-minded, moderate one.

Self-reinvention is necessary for any elite-centred doctrine. Although other ideologies have attempted it, neoliberalism stands out, not only by subverting a non-elitist philosophy (liberalism), but also for transforming itself while in power. The preachers of extremist free-market economics have upended the typical dialectical process of ideological development, grounded in critique and revisionism, which tends to resemble something more akin to progress. Perhaps this is what Francis Fukuyama had in mind when he proclaimed the ‘end of history’. And suddenly Ayn Rand’s dystopian USA of the future doesn’t look so far away.

Neoliberalism: the hijacker of old-school liberalism, the shapeshifter hiding in plain sight. For the perfect illustration of its metamorphosis, look no further than Britain’s Labour Party. The party’s first identity crisis was prompted by the initial emergence of neoliberal politics, encapsulated by the thumping election defeat in 1979 which topped off the general decline of the 1970s. So, eventually, the first reinvention: New Labour. And it worked—Tony Blair became the first Labour leader to win three general elections. Another period out of power, however, facilitated a shift back to the left. Hence the second transformation. Under Kier Starmer, today’s government has committed itself to the pillars of neoliberalism—fiscal prudence, anti-immigration, a very ‘Western’ foreign policy—more fiercely than any before it. Much like the neoliberal ideology itself, the only source of legitimacy the government has left is derived from a perverse relationship with its older self. Another ‘latebourgeoissociety’ post reminded me that the majority of people voted Labour in the last election ‘to get the Tories out’, not because they actually liked the party.

So, the goal posts have shifted, and the neoliberal doctrine, taken as divine, has been placed at the heart of all our politics. Rather like the rational, optimising ‘agents’ who characterise the neoclassical model, today’s political parties appear fixated on appeasing an imaginary voter: one who hates anything foreign, is terrified of someone else’s income tax going up, and is, often, already dead.

Alas, I return to my earlier predicament: read Ayn Rand, go to the pub, or scroll through Instagram. Choose none of them, a neoliberal agent would say, go to the gym and do some self-optimisation (then scroll through Instagram, read Ayn Rand, and go to the pub, in that order). ‘Latebourgeoissociety’ laughs at the neoliberals, but is that the right response? The Instagram reel is, after all, the form of the neoliberal’s propaganda. Jokes aside, it certainly gets one thing right: blame neoliberalism for the strange predicament in which the world finds itself. In the meantime, whether you’re in early or late bourgeois society, Galt’s Gulch, or just neo-reality, get used to your new friend: neoliberalism, bringer of fascism, gym culture, and the end of history.∎

Words by Jack Stone. Photo courtesy Brent Moore via Flickr.