‘I think of you when I shag my boyfriend’: Are we too attached to celebrities?

The above quotation is not a drunken confession to an ex, but a sign I spotted when I was at a Harry Styles concert. At the time, I was still deep in an overwhelming obsession with ‘Hazza’ and thought the sign was hilarious. It is only now that I have emerged from the depths of 2020-22, that I see it as, well, kind of weird. As a Harry Styles fan, a “fanatic” in the most literal sense of the word, my judgement was so distorted that I thought it normal for a woman to publicly confess, almost boast, that her attraction to a stranger who made it big on The X Factor interfered with her sexual relationships. I also believed with utter conviction that Harry Styles was one of the most revolutionary, creative musical artists to ever live. I considered his Vogue cover (which still hangs in my childhood bedroom, a relic) ground-breaking; my father’s attempts at enthusing me about David Bowie fell on deaf ears, receptive only to the opening chords of Watermelon Sugar. Luckily, as his hairline receded, so too did my adoration for him, and I now look back on this stage of my mid-teens not only with mild embarrassment, but also with concern about the impacts that this clear vulnerability in human psychology may have on ourselves and wider society. I doubt how healthy or happy my Harry Styles obsession made me, and adoration seemed to bypass any sort of critical thinking.

The rise of the parasocial relationship—a fan’s one-sided yet seemingly intimate relationship with a celebrity—corresponds with the rise of the first mass media publications in the 1700s. People often formed deep relationships with writers they particularly enjoyed, writing them long and detailed letters (careful, reader). Not only this, but when newspapers and magazines spread information about a particular person, they feed this fascination. The most absurd example of this was a public obsession with ‘Master Betty’ in the early 1800s, a child actor who amassed a thunderous, and at one point pistol-wielding audience, and whose diarrhoea became front page news. Clearly, there has always been something in our brains which allows for an obsession, adoration, or perceived relationship with someone we have never met. Psychologists have connected celebrity worship to mental illnesses such as Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and have likened fan behaviour to that of addicts: the connection the fan has with their idol is never enough, compelling them to consume more and more intimate details about them. Whilst this suggests that parasocial relationships are natural, it also highlights the psychological risks connected with them.

Entertainment and a desire for intimate connection often merge to form a lurid and insatiable fascination with a singer or actor’s personal life. The rise of social media and ‘doom-scrolling’ exacerbates this as the fan attempts to fulfil their hunter-gatherer instincts by replacing berries with interview clips or paparazzi ‘behind-the-scenes’ videos. We are put in a vulnerable situation: social media sites and gossip publications profit from our desire to know the ‘inside story’, pouncing on the tiniest morsel to drop into our mouths, open from shock at the slightest brush of hands between co-stars. Did Glen Powell and Syndey Sweeney really have an affair? Speaking of, did you see Sweeney’s body transformation? Don’t fall for the clickbait trap and search that up, please. If you felt inclined to do so, however, you may have highlighted a key fact in this issue: it is incredibly easy for gossip publications to grab our attention with sensational headlines, and before you know it, you have just spent ten minutes watching video compilations of Glen Powell flirting with his latest co-star on the red carpet. At this point, it might be time to accept that celebrities have exaggerated romantic chemistry to bring their latest project more traction—and money—since long before Brangelina. Being aware of how this part of human psychology is easily exploited, and frankly wastes our time, is the first step to creating a healthier relationship with the celebrity. Who needs to know that Harry—you know what, it’s not worth mentioning.

It almost goes without saying that the media’s exploitation of the parasocial relationship can be deeply invasive and harmful to the celebrities themselves. Prince Harry has just won a $12 million settlement and admission of illegal activity in a trial with The Sun, in which he accused them of hacking his phone and hiring private investigators to illegally gather information about him. In this case, the celebrity becomes a resource, their life and body a source of money and entertainment. We, the fans, feeling a real human connection to someone we still perceive on some level as fictional, take for granted that we are at liberty to dissect their private life.

This isn’t to say that celebrities do not also profit hugely from our capacity for the parasocial relationship. Of course, their entire brands are based on it. It is almost impossible to name an actor or singer who hasn’t done a brand deal, makeup line or fragrance (three words: Gwyneth, Paltrow, candle—what a beautiful symbol of the commercialisation of the intimate parasocial relationship). Taylor Swift, billionaire and—oh yeah—singer, has mastered the manipulation of the fan-celebrity connection. Her ‘easter eggs’, clues dropped into her songs and Instagram posts to suggest future albums or music videos, have become an admittedly fun and harmless way for fans to connect with her. Or at least, with her brand, which even takes advantage of their obsession with her personal life, coded lyrics suggesting a song could be about a certain someone (“the song is literally called Style, OK!”). Oh, how I love the great unification of art and capitalism.

The same lapse in our critical thinking which occurs when we buy a celebrity or influencer endorsed product is being increasingly and more dangerously weaponised in politics. Whilst being relatable to voters has always been an essential part of a political campaign, technology and social media have expanded the potential of this technique to a dangerous extent. It is not uncommon during a particularly mind-numbing doom-scroll that, shock! I am faced with Trump making some sort of insult or senseless joke. As I inevitably click on the comment section, I see comments like ‘not Donald Trump being low-key funny’. The skull emoji at the end of such a comment is a memento mori, a signifier that these videos subtly build a connection with the average Instagram scroller, who may not even actively support Trump. We see this again in Boris Johnson’s messy haired ‘Uncle Boris’ persona, or Nigel Farage’s trending appearances on Cameo, an app which lets fans receive personalised messages from a celebrity, and the reality show I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here!. Such media is propaganda, which uses a subtler form of the parasocial relationship to manipulate our perception of these politicians: it makes us regard them as entertaining characters, and desensitizes us to their dangerous amounts of power and influence.

Right-wing populists aren’t the only ones harnessing the parasocial relationship. When Taylor Swift endorsed the Democratic Party in the 2024 Election, there were a total of 405,999 visits to Vote.gov through the link on her Instagram story in the 24 hours it was live, compared with the site’s daily average of 30,000 in early September, according to a General Services Administration spokesperson. Of course, it is difficult to know just how much this actually affected the election (in hindsight, not enough), but it is easy to see how the opinion of someone whose personality you like and admire can influence your own. And it isn’t just the stereotypical, obsessed fan who is vulnerable to this. When I found myself nodding along to Rory Stewart of The Rest is Politics as though at a dinner party, I reluctantly admitted that an intervention in my podcast listening was in order. The format of the podcast is particularly apt at forming a connection, making one feel as though they are in a conversation with the hosts. There is no need to stop listening to such podcasts, but it is important to listen critically and remember that the ‘centrist dads’ represent a single political viewpoint. Hey, at least I have never written a ‘Roristair’ fanfiction (yes, it exists).

This is not intended as a vehement campaign against all engagement with celebrities. Identifying with a public figure can be immensely valuable in discovering more about oneself and feeling represented. It is normal to feel connected to the figure behind a piece of art or music which one engages with on a deep level. What we need to be aware of however, is that this phenomenon, which has clearly always been intrinsic to our psychology, leaves us vulnerable. It can cloud our critical thought, and cause us to make unfounded decisions. It can lead to unhealthy behaviours, especially within the dopamine-addicted world of TikTok and Instagram Reels. Personally, I have found that seeing celebrities as offering a service of entertainment, rather than as ‘friends’, has helped me to form a healthier relationship with them. This involves learning to accept that the feeling of such an intimate connection will never be substantiated with any real contact. So, if during a moment of intimacy with your partner, an image of Rory Stewart suddenly pops into your head, it might be time to consider: has this gone too far?∎

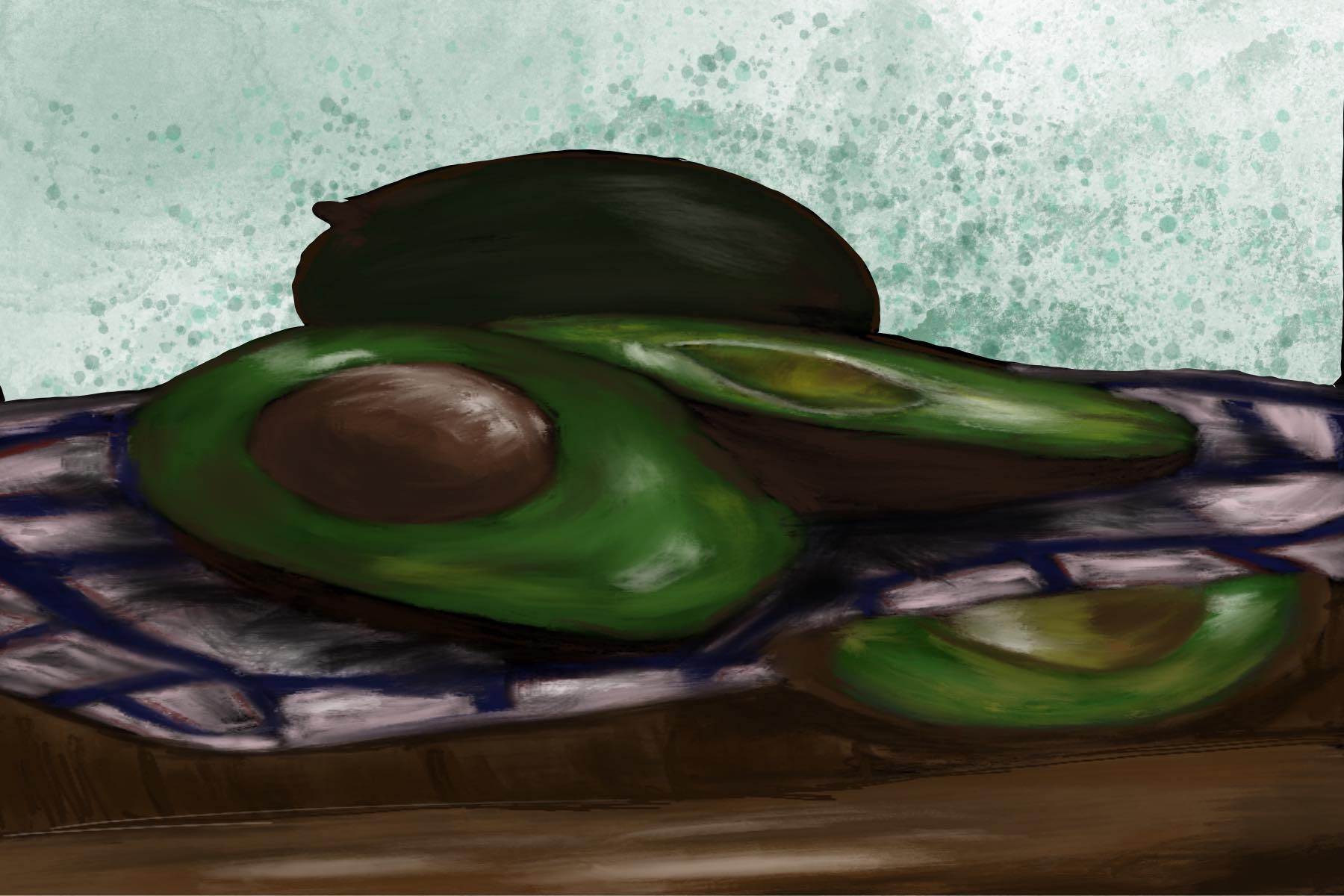

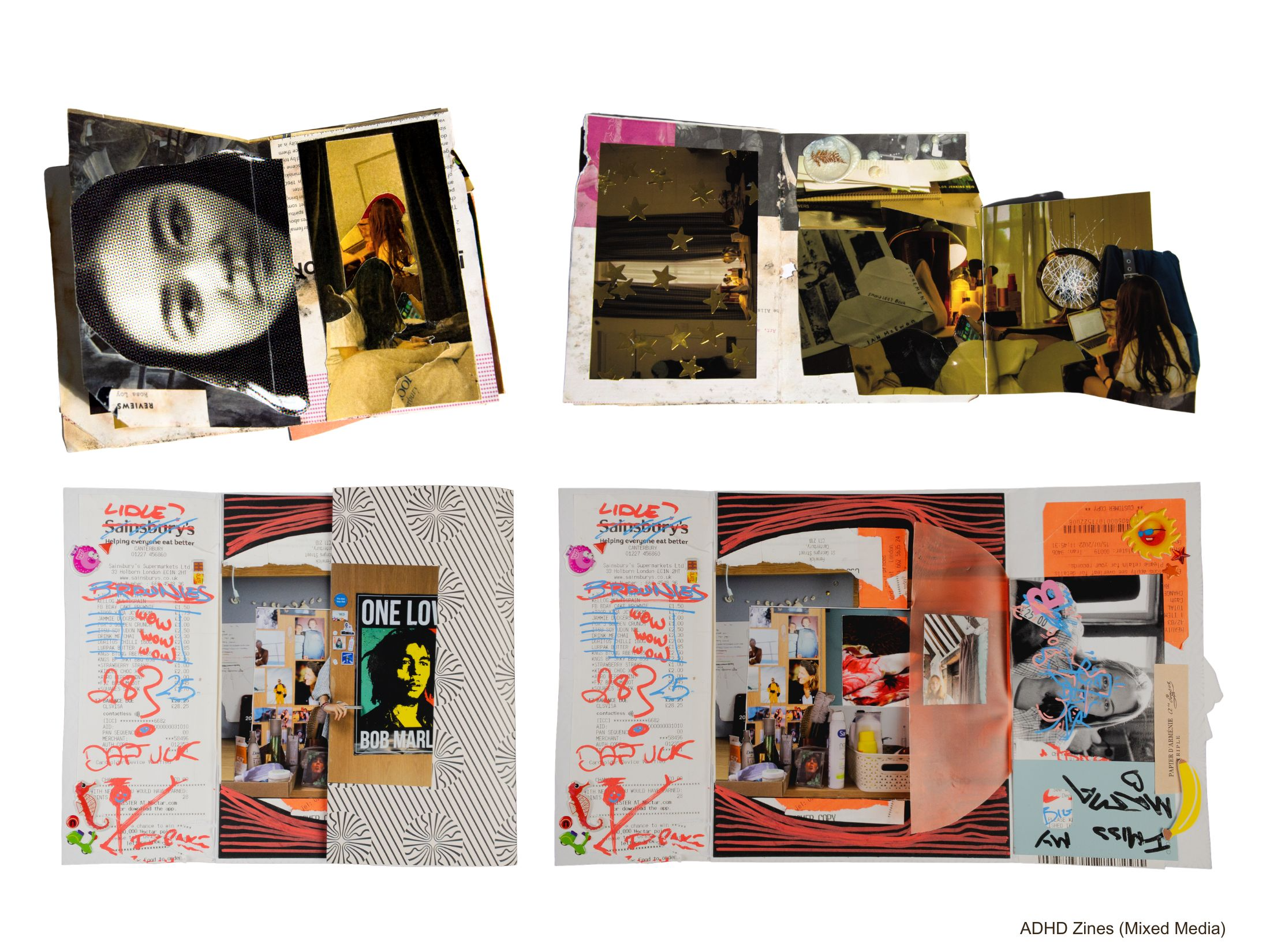

Words by Frieda Fahrenholt. Artwork by Libby Peet.