Fellas, is it gay to read a book?

The Saturday before last was a particularly sunny one. Although I didn’t have much time in my day to spend outside, I decided to take a break and spend half an hour or so reading an actual, physical book. I grabbed my book (On The Road by Jack Kerouac) and opened my window. My windowsill is big enough that I can fit my entire frame on it if I bend my knees slightly. I live on the ground floor, so if I sit like this, I inevitably enter the gaze of passers-by. This being a sunny Saturday, there were quite a few.

I couldn’t stop myself from envisioning how those passers-by might be perceiving me as I came into their view. What might they think? Would they remember me? Would they find me beautiful? Would they find me odd? I couldn’t help but try to adopt a pleasant yet intellectual expression. I wondered whether my outfit—jeans and a navy blue T-shirt, complete with armfuls of gold jewellery—matched my book. Did I look like the sort of cool, easy-going, esoterically earthy girl who might plausibly enjoy Jack Kerouac?

Something about it felt inherently performative, voyeuristic, attention-seeking. Part of me secretly hoped that someone would take a picture of me from the street, one that I could post on my Instagram story and caption “performative reading final boss.” Maybe a male manipulator would swipe up, saying he loved On The Road too!

“Performative reading”—an oxymoronic couple of words in themselves. Reading is a profoundly intimate, independent act. One of the most important skills children acquire in their first years of school is reading silently, for themselves, but learning to read begins as a kind of performance. As children sound out their first words, they are inevitably surrounded by legions of loving caregivers, parents, and teachers. Groups of children learn phonics in a sort of cherubic chorus, with the teacher presiding as maestro. Parents read aloud to their children before bed. As we get older, and become better readers, the majority of reading starts to happen silently, with the element of performance removed. By the time we finish secondary school, the idea that anyone might be asked to read aloud for any substantial period of time is laughable.

What is it, then, about my act of reading on my windowsill that transformed an inherently private, silent activity into one that felt so distinctively performative? Why did I find myself unable to focus on the genuine act of reading, and instead obsessed over curating my potential public image? And, importantly, why the urge to make fun of myself in the first place, to be so crushingly, achingly, pathologically self-aware that it prevented me from just actually fucking reading On the Road (which I still haven’t finished because I felt the need to write this piece instead so I can post this on my story as well)?

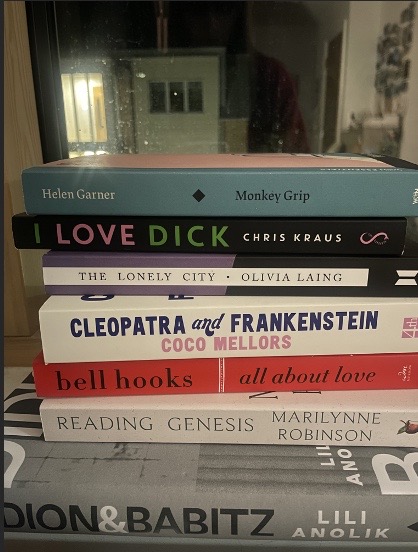

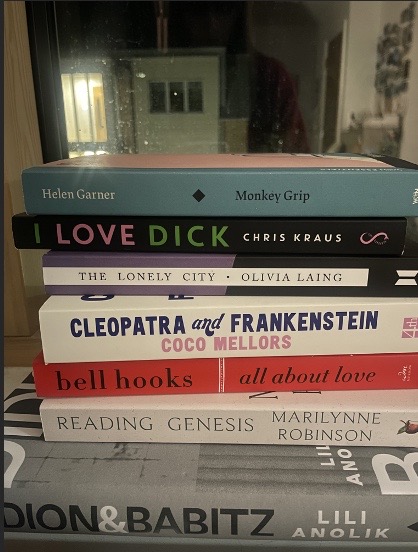

The widespread characterisation of reading in public as an inherently performative act reflects our inability, as a society, to take anything seriously. Our current cultural moment is plagued by a famine of earnestness. Everything is a joke. Everything is ironic. There are few acts more earnest than reading, specially something thoughtful and literary. Gone are the days where a self-improving act, like reading, can be divorced from the commodification of the self. In an age where we’re all walking, talking billboards of self-expression, even the cover of the book you’re reading serves as an important signal of your personal brand. Would someone with a cool girl Instagram profile full of film shots, Miu Miu Tabis and half-drunken wine glasses ever be caught dead reading Colleen Hoover? If you spend any amount of time on the same corner of the Internet as I do, you’ll know that she’s much more likely to be reading Sally Rooney or My Year of Rest and Relaxation.

But the problem with good books—really good books—is that they are necessarily exercises in earnestness. Something is lost when we commodify the aesthetic of their consumption. Good books are amazing: they can sink so deep into your skin that they become a part of you, influencing how you write, what you think, and how you behave. One of the most genuine, earnest human experiences on this Earth is the feeling of being touched by something you’ve read, when it feels like the words themselves have reached out from the page and embedded themselves in your heart. I’m aware that’s a soppy, desperately earnest, clichéd sentence. Isn’t that exactly what it feels like to read a good piece of literature? To be confronted with your own desperate, disgusting earnestness?

And who is allowed to be earnest in our society? To be emotional? Very few of us, least of all men. Memes about performative reading are almost invariably poking fun at men who read “feminist literature books” (redundant shorthand for any book written by a woman), which they presumably carry around in their tote bags whilst listening to Clairo and thinking about becoming DJs, in order to appeal to women. By usurping this uniquely feminine activity, and wearing a mask of genuine earnestness, these male manipulators can ensnare cool girl literary girlfriends.

The idea that reading fiction is a feminine activity is not a new one. It’s been documented for some time now that women are more likely to be avid readers than men. Even amongst readers of both genders, women are more likely to read fiction. Every meme I see poking fun at so-called “male manipulators” who engage in performative reading is imbued with the undertone that there’s no way a straight man would read important, interesting literary fiction in earnest. Implicit here is the message that important, powerful, and provocative books, like Sally Ronney’s Intermezzo, or Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie’s Americanah, or Toni Morrisson’s Beloved—which all just happen to be by female authors—can only be authentically read and enjoyed by women. If a man reads them, there’s no way he’s doing it for the simple pleasure of reading excellent literature. No! The only thing he’s trying to enjoy is a literary cool girl’s pussy. Surely this is the final iteration of pick-up artistry: he’s trying to signal to women that he’s a particular kind of person. He’s intellectual, sensitive, understanding—he even READS! Books! Written by WOMEN! That’s several hours of valuable podcast-listening time down the drain.

These kinds of memes, admonishing men for pursuing what has been deemed a feminine activity, are dangerous and patriarchal. They imply the worst in men: that there’s no way they could be genuinely intellectual, gentle, passive enough to partake in the act of private reading. An ulterior motive is imposed, one that presupposes that reading is an inherently emasculating act. Why else than sexual gain would a man ever willingly, publicly emasculate himself?

This gendered memeification of reading also comes at a time where the gender divide seems to be worseningevery day. Women outperform men in most graduate fields. The political divide between young men and women is, if the Opinion section of any major newspaper is to be believed, bigger than the Pacific Ocean (and only getting bigger). In an age where feminism is kicked increasingly to the curb, and populists view young, disenfranchised men as their primary target audience, I can’t help but notice the sinister undertones that underlie the vilification of men reading in public. It implies that reading is something men—indeed, anyone—should be embarrassed to admit to. Increasingly, I feel that reading a book is an act of resistance in itself. When I choose to put down my phone, to divest my attention from the social media apps owned by despicable billionaires, I cease (momentarily) to be a product. My attention ceases to be profitable. I pick up On The Road instead. When interesting sentences catch my attention, I think. That thinking makes me smarter. I wonder who could possibly gain from making me believe that public resistance is embarrassing.

We have so much to lose if men feel embarrassed to partake in such resistance. Men are told by pundits like Andrew Tate, Elon Musk and Steve Bannon to be tough, macho, and unfeeling. Reading, however, requires earnestness. Resistance, that is, meaningful political resistance to systems of oppression, requires earnestness. No one is going to fight for a cause they don’t earnestly believe in. No one is willing to dismantle a system they don’t earnestly believe to be wrong. Let men be earnest again—let everyone be earnest again.∎

Words and photo by Kalina Hagen.