Coquettes-who-read vs deepfakes

I failed my interview for journalism school. In my application, I had written about my passion for telling human stories—the kind that give depth to reality through narrative. And so, they asked me: “Pitch a human story on the AI Summit” (nothing ironic about that). I panicked and gave a bland answer—an interview, as if that alone could inject humanity or originality into the subject. My interview failure wasn’t just a personal disappointment. It was a broader disconnection between traditional storytelling values and the new realities of AI-influenced media.

The truth is, even as a voracious reader and journalist-to-be, I’ve always kept AI at a distance in my intellectual interests. I use it every day. I know it’s shaping our present and will define our future. But it felt unrelated to what I cared about most—the quiet weight of a long text, the stories told like they’re lived.

It wasn’t until after my failed interview that it hit me. I was scrolling through Reels, coming across yet more deepfakes—funny ones of politicians’ speeches, reconstructions of the building of the Pyramids of Giza, orcas ‘saved’ by benevolent scientists. By now, we all know that these images are slowly killing the idea of visual truth. But that day, for the first time, the thought didn’t depress me; it almost made me hopeful. If AI is gradually stripping images of their credibility, maybe text is about to reclaim its place as the most reliable way to tell the truth—because people will start looking for it again.

We could add generative AI to the endless list of reasons that disprove the saying “seeing is believing” (belief is not the same as knowledge; perception alone does not guarantee truth, etc, etc). But this abstract reflection takes on a new dimension when we consider the way AI actually works, as Grégory Chatonsky, artist and pioneer of digital art, explains: “AI-generated images represent what we want to see, rather than what is,” and the major shift lies in the very mechanics of AI software, in its principle. The data it relies on, the web as a space with its own “narratology” that is distinct from history. In other words, AI generated content mirrors the way the web reflects the world, rather than the world itself. It is not simply a distortion of reality but a vicious cycle that caters to specific desires and symbols, performatively perpetuating them.

During the Industrial Revolution, images entered the public space as “indices of reality.” That is not to say they were ever an irrefutable proof of anything, but as Chatonsky points out, photographs and videos were at least grounds for discussion. Today, deepfake practices challenge even that function, significantly shaping public perception of the media landscape and threatening journalistic credibility at a time when trust in the press is already eroding year after year.How do we imagine a future for information that is neither defined in conservative, paranoid terms nor blindly technophilic?

While I was having my little revelation about AI’s potential impact on text, media organisations were already scrambling to adapt their strategies in two distinct ways. On the one hand, they have been exploiting AI to automate certain tasks such as the production of basic content, data analysis, and the personalisation of user experiences. On the other, battling the disinformation facilitated by generative AI technologies, which can create misleading content on a massive scale. The media world is preparing itself, and conferences on ‘new practices in journalism’ are flourishing. The key questions they’re trying to answer are how to ensure transparency, how to rebuild trust, and how to rethink formats.

But while numerous interesting solutions are emerging, they seem to be addressing pre-existing problems that AI merely amplifies, like polarised information, biased algorithms, and a media logic driven more by consumption than by knowledge. More generally, the tone of these reports sometimes gives the impression that we must now bow our heads to convince citizens of the necessity of the press in a democracy, as though persuasion will come through form rather than content. This paternalistic tone carries a quiet sense of defeat. Must “digital natives” be grotesquely begged to take an interest in reality?

Urgency forces solutions, and not all of them are to be dismissed. But the media and intellectual public landscape both lack a substantial, overarching reflection on the blow dealt to the ‘image’ today, and this prevents us from truly projecting into the future of information. The whole ‘innovative’ house of cards risks collapsing with every new technological advancement if we do not agree on certain premises, on values we still subscribe to.

In fact, these tactical responses ultimately fail to address the deeper philosophical question at stake here. We might legitimately ask, for example, whether information still has meaning in people’s lives. We might ask whether the pursuit of truth is still something that matters in personal and collective understanding. Because that is not a given. Paternalistic or commercial narratives and strategies postpone the moment when the question must be faced. Despite biases, fascistic political threats to information, the individualisation of societies, and the appeal of entertainment, I believe the human thirst for genuine knowledge and authentic understanding will find ways to survive.

Alongside these new media solutions, we often hear that print journalism is dying. No one buys physical newspapers anymore, media outlets are adapting their strategies to digital formats, and I’m told not to specialise in print journalism because ‘there’s no money in it’. Will this trend reverse?

I was intrigued when France’s flagship newspaper, Le Monde, sent me a notification after the meeting between Trump, Vance, and Zelensky, which read: “Trump Zelensky, the verbatim of the verbal escalation at the White House.” A transcript, with no context or analysis. And I thought: are our journalistic beacons transforming into mere recording machines (highly reliable ones, granted)? No. But perhaps they have understood that when reality starts to eerily resemble a deepfake, we must return to the script. To words. To silences. When laid bare, without interpretation or paraphrase, they can, in certain contexts, be even more striking. In their coldness, we grasp the gravity of a situation without needing someone to explain it to us. These-words-were-said. I read them. They are true.

It is no coincidence that the most serious or significant speeches and conversations are the ones published textually, as they are. The publication of direct sources attests not only to the public’s ability to think for itself, but also to the need for words that we know certain professionals have reliably recorded. This is the ‘objective’ aspect of the contemporary need for text.

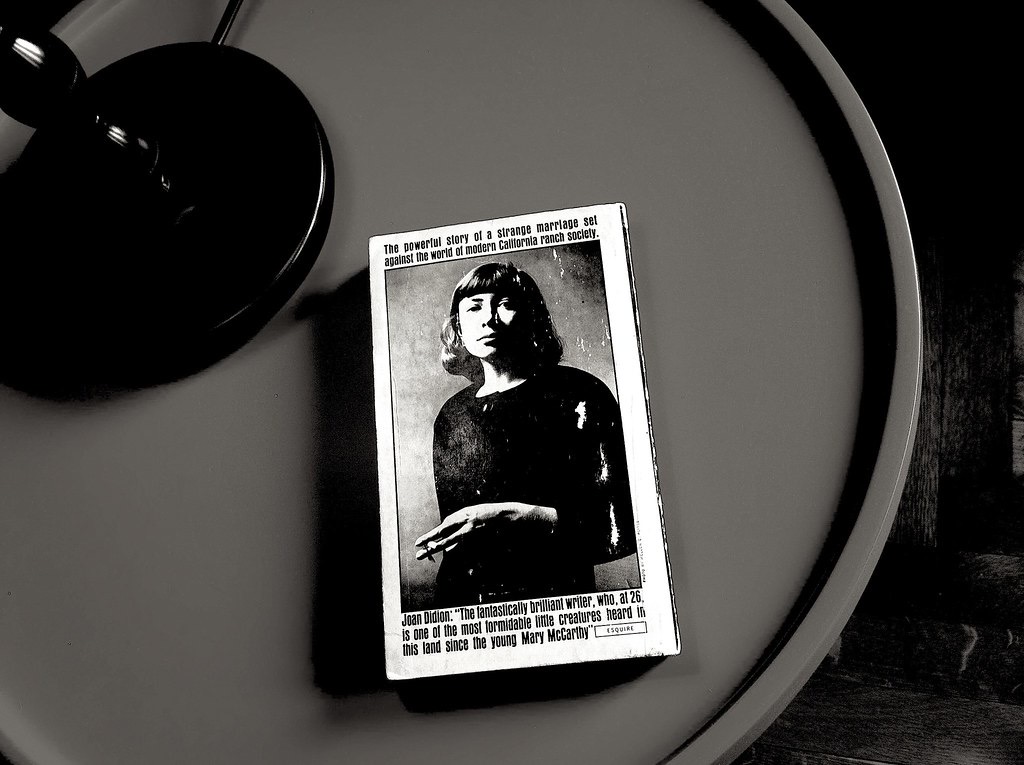

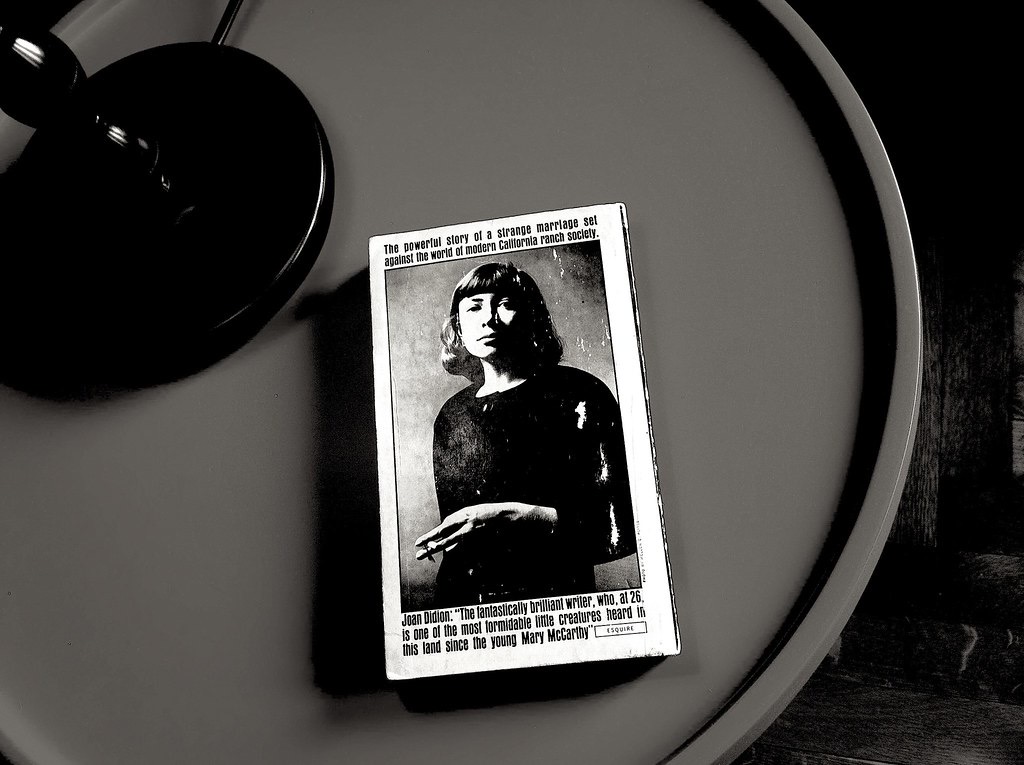

More than that, trust in the press generally, and the appeal of text in particular, will come from clearly embracing subjectivity. In a landscape where competing claims to truth proliferate while evidence grows increasingly contestable, authenticity becomes the distinguishing factor. Few figures embody this better than Joan Didion—who, ironically, has become something of a cult icon on Instagram meme pages, romanticised by coquettes-who-read, and transformed into tote bags and aesthetic start-up packs. And yet, that very popularity illustrates my point. Because behind the aesthetic, the writer herself remains : Didion, whose sharp, interior gaze shaped Americaxn new journalism as much as any of her louder male contemporaries.

Through her subjective lens, she meticulously documented expressions, emotions, and silences—all the human elements that AI will never truly capture. She told true stories, borrowing techniques from fiction. Not only is assuming one’s subjectivity sometimes more ethical than striving for impersonal truth, but as a reader, I find it far more compelling to be drawn into reality through its strangeness, its shock, its beauty, its sorrow. This way, emotions take the place they deserve in journalistic storytelling, without being dismissed as mere sensationalism. Reader curiosity is no flaw.

When conventional journalism fails to capture society’s seismic shifts, narrative journalism steps into the breach—at least according to John Hartsock’s analysis of American media history. The pattern is striking: during the waves of migration and economic instability of the late 19th century, amid the Great Depression and world war of the 1930s and 1940s, and throughout the cultural rebellion of the 1960s and 1970s, narrative journalists emerged to tell stories that traditional reporting couldn’t contain. Those stories were vital responses to moments when established frameworks crumbled under the weight of lived experience.

This historical perspective on narration in news writing reveals an enduring tendency that hints at journalism’s future in an AI-saturated world. In 2025, perhaps the time has come for a new new journalism. Indeed, this may be the real challenge generative AI poses to the media: not merely fact-checking its distortions, but proving that stories, when told well, still matter. The next time I try to get into journalism school, I might say that the most human story has nothing to do with an interview, and everything to do with our collective search for authenticity in a world where the adage ‘seeing is believing’ is irrevocably obsolete.∎

Words by Prune Fargetton. Image courtesy of Incase via Creative Commons.