Half the population, only half the story: Western tourism’s revival in Afghanistan

“During a trip through Afghanistan, you will see beyond the turbulent current era and experience a beautiful country with a rich cultural history.”

Safarat Travel

One travel website offers paid tours throughout Afghanistan, promising to take the keen explorer places which will reveal the country in a brand-new light. Another advertises a trip which crosses over “invisible lines in the map that explain Afghanistan’s recent and often bloody past.” But wait—would anyone like to answer for its often bloody present?

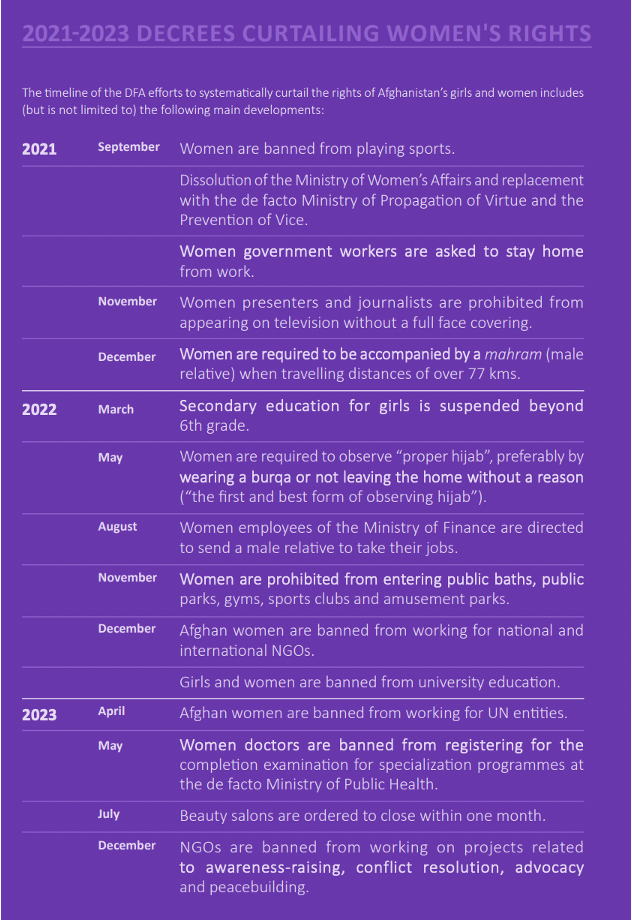

In both instances, it’s hard to see ‘beyond’ the turbulence of Afghanistan’s current era. Women under the Taliban regime are victims of what the United Nations has since 2023 been calling ‘gender apartheid’ in an effort to recognise the systematic suffering of 49.5% of the Afghan population. Most recently, the Taliban have introduced a law whereby new buildings cannot have windows which overlook the (very few) areas where women are allowed—wells, courtyards, kitchens. This is to add to the list, 80 laws strong, which has only expanded since the Taliban’s takeover in 2021: no jobs, education, or free movement; no visiting parks, no singing, and no audible speech, even in prayer.

So: tourism to Afghanistan. To holiday, or not to holiday? Such are the ethical questions that one travel website poses on a webpage fittingly titled ‘Ethics.’ This is followed up with a frantic series of questions: “What are the moral implications of visiting Afghanistan as a tourist? Is it in poor taste? Is it voyeuristic? Are we offering dressed up war tourism?”

This is not a debate over the treatment of women. To debate would be to suggest that there are two sides to the treatment of women, one of which maintains that the lack of human rights for women in Afghanistan is acceptable. Debate over the merits of war tourism is more validly two-sided, however. Unpicking this debate highlights the West’s elliptical, if not entirely oblique, attitude towards women’s rights in Afghanistan.

Returning to the traveller’s moral qualms one by one: How do travel sites deal with the moral implications of their offerings?

Tour organiser “Culture Road” suggests that given the—vague and unspecified—“political and cultural shifts” which Afghanistan has gone through, the tour group will “operate in a way that respects the local norms and values while ensuring that our guests have a worthwhile and welcoming experience.” Respecting such cultural values as “always wear local clothes when we go outside”; “don’t walk in front of someone who is praying” and knowing that “it is forbidden to bring alcohol into Afghanistan” is a very different ball game from “respecting” the Taliban’s legislative decision to deny basic rights to women. Which is to say, whether individual citizens subscribe to a cultural norm in which accepts female oppression, this norm has nevertheless been imposed upon and inculcated into Afghan culture through a systematic build-up of restrictive laws targeted at women. To ignore this in favour of ensuring a “welcoming and worthwhile experience” for Western tourists is to condone, albeit implicitly, female suffering under the Taliban regime. The failure to take an active stake in the “debate” is still not a decision: there is a sense on these travel websites that because the tour-group members will return to their respective Western nations, they are exempt from this “debate” altogether.

In lieu of a sufficient answer to the first question, let’s try the second. Is travel to Afghanistan in poor taste? In an interview for the BBC, British tour guide Sascha Heeney explained that “there’s a big market for that kind of travel out there.” Apparently, enough people are interested in “that kind of travel”—that vague kind of travel you engage in when you have a gut feeling that there’s something morally dubious about it. So of course. That kind of travel. If not a “big” market, tourism to Afghanistan is certainly growing: the number of tourists rose from 2,300 foreigners in 2022 to 7,000 in 2023. The number is continuing to grow since America withdrew its troops in 2021 and the Taliban seized nation-wide control.

Other kinds of that travel come under less scrutiny than in Afghanistan. In 2024, Pakistan ranked as the second worst-performing country in The World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index. Is it tasteful to travel to Lahore in light of this analysis? Perhaps more provocatively, we might ask whether it is still tasteful to travel to America in the wake of the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Is travel to liberal California less ethically compromising than travel to Alabama, with its fully-enforced ban on all abortion? Perhaps these questions are extreme, polemic even. But they do somewhat check the Western assumption that it can evaluate other cultures without bias, or still more hypocritically, that the West provides the standard from which the rest of the world deviates.

Part of figuring out whether—or more to the point why—travel to Afghanistan is in poor taste comes from teasing out whose taste these travel websites are catering for. Hence, perhaps, the third question, which worries that travel to Afghanistan is voyeuristic. Indeed, between concerns over tastefulness and voyeurism, the website may as well openly reassure prospective clients that travel to Afghanistan does not. have. poor. optics. This is a specifically Western concern with how the West will perceive Western tourists’ decisions to travel to Afghanistan. Moreover, the question of voyeurism emerges from the West’s (necessarily political) decision to look the other way—there is something strangely voyeuristic when a small group of Western citizens look close-up at a country at which their nations are no longer looking. To state this economically, aid to Afghanistan has decreased. The UK spent £246 million in foreign aid to Afghanistan in fiscal year 2022-2023; this reduced to £100 million in 2023-2024. Though foreign aid was inevitably funnelled towards other conflicts in FY24, these figures illustrate the stark reality that the people of Afghanistan—as distinct from the Taliban—are largely (conveniently?) losing attention.

Opposite from foreign aid are sanctions. Imposing sanctions is, theoretically a means of inducing political and economic pressure; eschewing sanctions is, theoretically, a means of keeping the national economy afloat and therefore prioritising the interests of the individual citizen who would suffer in a declining economy. The UK currently applies sanctions to 135 individuals and five entities in Afghanistan, small fry compared to Russia, the most sanctioned nation in the world, with 1,733 individuals and 382 entities sanctioned as of February 2025. The significant difference, however, is not so much the number of sanctions—Afghanistan is a smaller nation geographically and economically—but the fact that sanctions on Afghanistan have not changed since 2022. Regardless of the stance adopted on the efficacy of sanctions, this highlights the lack of attention Afghanistan receives even within the policy-making sphere. With such rapidly regressive changes to Afghan civil law, foreign policy surely requires reconsideration three years on from the imposition of these initial sanctions.

By contrast, where media attention falls on Afghanistan, four years after the Taliban’s takeover, it is becoming increasingly polemic and less productive. Ultimately both ends of the political spectrum use Afghanistan as a bargaining chip in Western disputes rather than a country where women are suffering in actual fact. Taking the UK as an example, on one end of the spectrum is far-right Islamophobia which uses the subjugation of women by an Islamic regime as one pawn among many in its populist rhetoric. Robert Jenrick’s recent vitriol claimed that “importing hundreds of thousands of people from alien cultures, who possess medieval attitudes towards women, brought us here.” Fittingly, he made this claim via X; Jenrick’s inflammatory comments were spurred on by Musk’s use of rape gangs in the North-East of England in Islamophobic rhetoric.

On the other end of the spectrum is a globalist response which argues that we must continue to engage with the Taliban despite their treatment of women, in hopes of nudging them away from gender apartheid. Think tanks such as Chatham House—‘Afghanistan: Money can be the milk of moderation’—propose that we can only maintain influence over Afghanistan through fiscal engagement rather than distance. This approach, for example, rejects sanctions as a useful tool. Both responses use the women who are suffering as incidental to their arguments. The former twists their suffering into an argument against Islam as a religion, though the Taliban are hardly a representative sample of this community. The latter uses their suffering to justify Western intervention, so successful previously, in Afghanistan, again ignoring that it is the Taliban, and not the Afghan population, who are at fault. Either way, it is the Western perspective which is at the heart of this response, a perspective which, given we are unable to escape it, we should at least acknowledge openly.

Considering the final question, then: to ask whether these travel groups are “dressed up war tourism” is merely to equivocate on this Western perspective. Evidently war in Afghanistan is over, such that it is widely touted a ‘safer’ country. America’s withdrawal put an end to 43 years of near-constant war, with the UN estimating that by early 2022, fighting diminished to 18% of its pre-withdrawal levels. Of course, none of these levels consider the ‘soft’ violence enacted on the female half of the population through the Taliban’s laws.

It is, therefore, the aftermath of failed Western intervention and withdrawal which is dressed up for the tour groups. And if these groups are a kind of journalism, then it is not journalism which engages with the language of gender apartheid. The language of gender apartheid does not speak, as these travel websites do, of the “population” of Afghanistan as one equal mass. The language of gender apartheid does not fail to mention that when “most” Afghan citizens concede that “the general security situation has considerably improved” in their nation, 49.5% of the population were unable to weigh in. I’d like to see just one of these tourism websites acknowledge its engagement with a gender apartheid state. Not offer a different perspective on Afghanistan—you can look at the Hindu Kush from Tajikistan. Not offer funding for Afghan NGOs—as of 2023 NGOs were banned from working on peacebuilding, advocacy, and conflict resolution projects. Not offer jobs in Afghanistan—women are banned from working.

But until then, at least we have this optimistic, ear-to-the-ground, finger-on-the-pulse-of-global-sentiment, promise from a British tour guide (at Safarat Travel): “I believe that Afghanistan could become one of the jewels of world travel, if the political and security situation continues to improve.” I think he should be told:

(Image from UN Gender Profile on Afghanistan.)∎

Words by Clara Hartley. Image courtesy of Johannes Zielcke via Flickr.