Beer is Arab, but whiskey is European

Part I

July, 1961. In the northern suburb of El Menzah, Tunis, a secretary types as a beleaguered doctor dictates. Tunis – a city described by the Palestinian Poet Mahmoud Darwish as ‘the smell of night musk and salt’ – was a vestige of an eroding cosmopolitan Mediterranean, a city of multiple confessions, faiths and lifestyles. And just like the afflicted doctor, that was soon to wither away. Treatment in the much colder Moscow had proven ineffective. Now, a prognosis of Leukaemia in the Midsummer. The relentless midsummer of Tunis.

Relentlessness seemed to linger in the air, in the form of humidity and hubris. The doctor was incessant. Only fatigue would stop him. Years later, his secretary would recall that he never took aspirin or a transfusion, never paused for a nap, or even sat down when he spoke. He was a man, famously impatient, now in a race against his own impatient body. And he would win it. That July he would finish dictating his final book. A close friend of his described his bedside readings of the piece as reminding her of “a great classical hero who has been wounded in battle.”

Classical heroes rarely live to see their tales capture the imagination. A Saint is hardly consecrated before death. The doctor was no different. On October the Third, he was informed, by letter, that the preface to his book by the luminary Jean Paul-Satre was ready. There was little time for excitement, for the day prior the convulsing doctor had been flown to Rome, a pit-stop to then be flown to the United States – a nation he despised as “the country of lynchers.” Two months later, December 3rd, an Algerian friend brought the moribund doctor a copy of his now-published book. As his wife read him a gushing review, he is reported to have said “It won’t give me back my bone marrow.”

He was right. Three days later, he died. Aged thirty-six.

The doctor’s name was Frantz Fanon, a Martiniquan psychiatrist who committed his life to an intertwined struggle of psychiatry and service to the Algerian cause for independence, as well as decolonisation as a whole. He would not live to see an independent Algeria. As his body gnawed away at itself, colonial violence seemed to be reaching its apex. The Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS) – a terrorist organisation determined to maintain French colonial rule – would extract the most repellent violence against the native Algerian population; while in the French metropole, Algerian demonstrators were massacred by the Seine. Yet in these agonies, hope shamelessly prevails. Just as Fanon’s dying breaths produced his most acclaimed piece, the final patters of blood would see Algeria independent in 1962.

The Wretched of the Earth is a testament to what haunted Fanon’s mind. A canonical text of postcolonial theory, the book has become something of a cultural spectre, looming over, almost haunting the world with its impact. Fanon speaks eclectically and furiously about colonialism; he is scathing in his critique of certain elites and leaders in newly independent colonies; he is impassioned (and maybe even contradictory) in his discussion of violence; he is part theorist, part psychoanalyst; he is sombre and analytical, yet also frenzied and sensual; he is a zealot for the masses and above all he is hopeful, desperately hopeful for the Algerian cause. There is a real sense of identification and optimism for what Algeria could be. Unfortunately for Fanon, the Algeria of independence would resemble the post-colonial dispensations he criticised far more than what he was so desperately hopeful for.

For Fanon, the advancement of underdeveloped countries must be achieved through policies rooted in the masses. He sees the contact between Algerian intellectuals and the Algerian people – ‘that mass of starving illiterates’ – as delivering the policy that is ‘one of the greatest services that the Algerian revolution;’ a model for the post-colonial world. And yet, the question must be begged: who are the masses that Fanon sought to emancipate as he drew his dying breaths?

Fanon positioned the peasantry, and rather quaintly the lumpenproletariat (hence to be referred to as lumpen) as the forces of revolution. The latter is an archaic term that is as controversial as it is vague. It derives from the Marxist jargon and thought that was so popular when Fanon reached his intellectual maturity. Marx describes the lumpen as: ‘Vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged convicts, runaway galley slaves, swindlers, charlatans…pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, procurers, brothel keepers, porters…organ grinders, rag-pickers, knife-grinders, tinkers, beggars; in short, the entirely undefined, disintegrating mass.’ Scum, essentially.

Unlike Marx, Fanon’s humanism shines through. He is almost messianic in his descriptions. He defines the lumpen as the people of the shanty-town: the landless peasants that colonialism has disenfranchised and have now become those living on the margins of the cities. Fanon’s lumpen are the beating heart of the urban revolution, the ‘horde of starving men’ that become ‘one of the most…radically revolutionary forces of a colonized people.’

But as much as Fanon extols the lumpen for what they will do, Fanon does not seem interested in how the lumpen express themselves outside of sublime radical violence. If he were to do so in the Algeria he loved so dearly, he would find Raï. For the lumpen of North Africa are listening to Raï in the backstreets of every city, in the backseats of every car and on the backend of the dingy boat headed to Lampedusa (or maybe Dover?).

Raï was sown in the womb of the colonial era, conceived in the Oranois of western Algeria,the intellectual product of an unhappy marriage between the city of Oran and the countryside that surrounded it. Oran was the epitome of the urban cosmopolitanism that emerged in the French colonies of North Africa; a city of multiple faiths, confessions and lifestyles, shining par excellence for its nightlife and its mosaic of heritages, where affluent Muslim and Jewish Algerians could (sometimes) comfortably interact with European settlers. But this metropolitan bubble could only be sustained through colonial domination, where Algerians faced periodic low-intensity warfare; the banalities of everyday violence and criminalisation, and the impoverishment of their property, legal rights and humanity. The political culture of European settlers in Oran was often marked by repugnant anti-semitism, indeed, the beaches for which the Mediterranean is so famed had signs that read “No dogs or Arabs.” In the Oranois country, the fruits of colonial blight ripened. The harrowing tales of the French ‘scorched-earth’ policy are perhaps best described by their perpetrators: in 1841, General Saint Arnaud could describe ordering and witnessing ‘with a frightening indifference’… ‘All the villages, some two hundred in number…burnt down, all the gardens destroyed, all the olive trees cut down’ and how they ‘burnt everything’ and ‘auctioned women to the troops like ‘animals,’ leaving refugee women and children to die of ‘cold and misery’ in the Atlas Mountains.

Through abject brutality and an innumerable set of arbitrary measures justified through the unjust, French colonial policy transformed the Oranois. The lands that Arab tribes had grazed for centuries were now confiscated; prime agricultural plantations were now owned by European settlers, where poverty-stricken peasants and pastoralists migrated for meagre wages. The devastation imposed on the Algerian hinterland also saw a large number of peasants and pastoralists migrate towards the cities – seeking refuge from rural misery, Oran (or more appropriately, Oran’s slums) became the centre of migration from the masses of Aïn Témouchen and Tlemecen. A picture begins to emerge in western Algeria of an increasingly dispossessed native population in the country, and their alienated cousins in the cities. Fanon’s lumpen thus began to fully crystallise by the early twentieth Century.

The new emigrants to Oran, newly divorced from their lands, would bring Malhun music to their ghettos; performed by respected masters of the art called Cheikhs, they sang in the rich local vernaculars of western Algeria and eastern Morocco, articulating a pious worldview of bedouin raids, pure-bred horses and heroes of resistance against the French. The Cheikhs were intellectuals of an era rapidly turning bygone, the communal ties that defined tribal organisation dissipating to the realities of life in Oran. Yet their sound proved adaptable. By the interwar period, it had sired an urban twinge to their rustic voices, performed primarily in Arab urban cafes that were known to the French as ‘cafs maures’. Central to this emergent genre was the Gasba, a reed flute that hums a wooden tune to the coarse vocal shakes of the performing Cheikh.

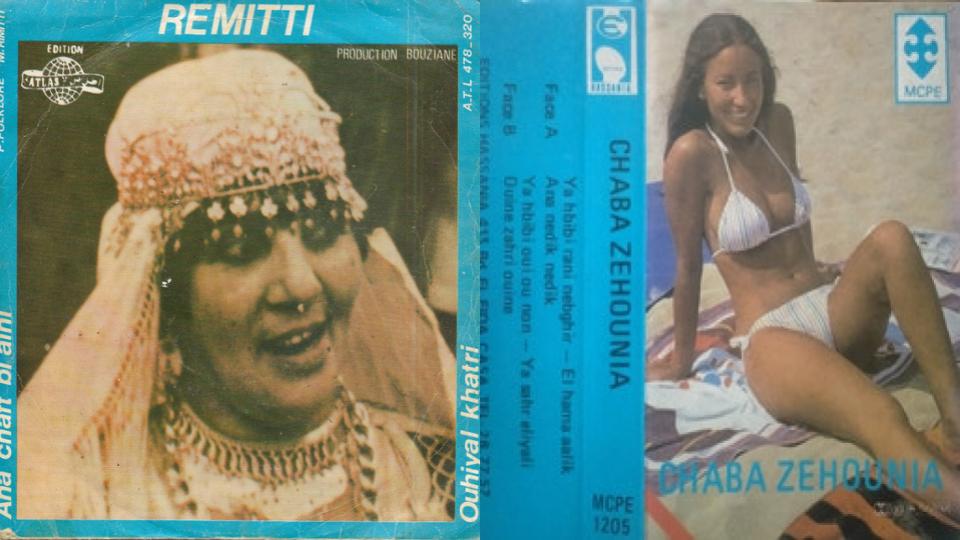

The Gasba was also used by another strand of performers known as the Cheikhat – the female form of Cheikh. However, unlike the Cheikhs, they articulated a worldview that was far more rooted in and cognisant of the despair of the lumpen than the veneration for tribal society of the Cheikhs. They were themselves on the very margins of society, associated with brothels and prostitution, and accompanied by dancers and shepherds – respectable society (both Algerian and European) saw them as dishonourable, and resented them as an underclass. Unlike the other prominent strain of female performers, the Meddahas who sang songs of religious praise in gender-segregated settings, the Cheikhat sang raw and provocative lyrics in gender-mixed settings where alcohol would flow. They would sometimes travel, performing at festivals for local saints, in public squares, bars and cabarets.

Their flirtation with the risqué was not necessarily a revolt against the traditionalist values of Islam or the conservative patriarchy of Algeria. The Cheikhat were the daughters and mothers of a deprived peasantry. The interwar period was characterised by displacement of natives and massive land acquisitions by European settlers. The Oranois as the most fertile region of Algeria soon became the epicentre of massive vineyard estates that hosted hundreds of thousands of seasonal and permanent toilers. Plantation owners preferred the employment of women as they were seen as easier to manipulate, and from these ranks of these summer seasonal workers arose many of the Cheikhat. For these lumpen women; in the country, they faced brutal exploitation, famine and cholera; in the cities, acute unemployment and marginalisation. Unable to protest, they sang. Their disaffections and struggles were channelled in the lyrics.

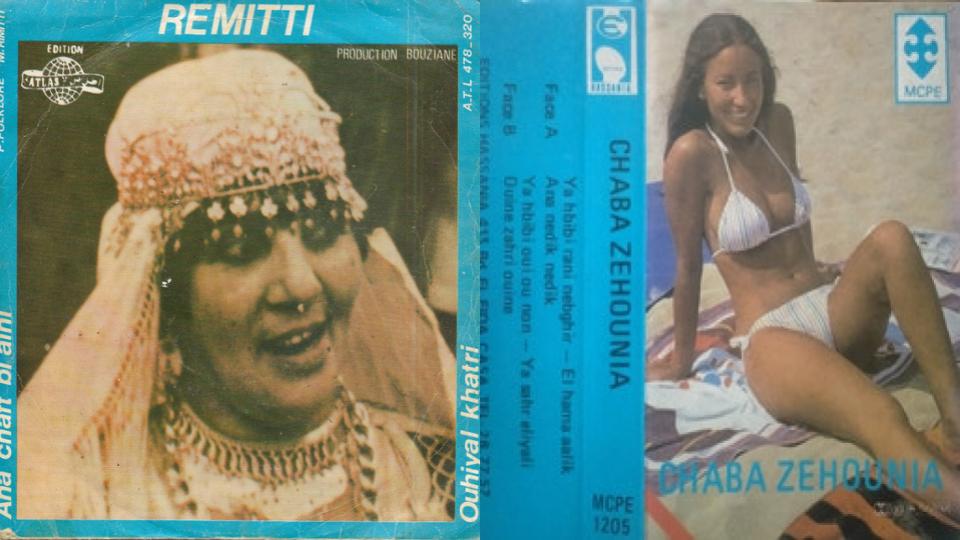

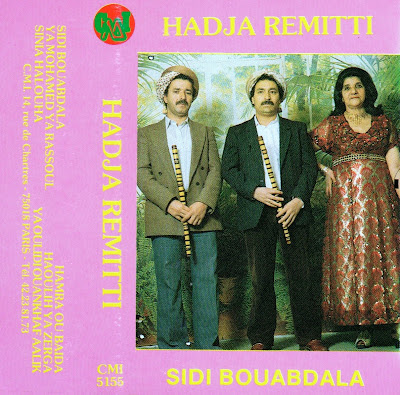

Within this milieu, icons like Cheikha Rimmiti and Cheikha El Oushma (The Tattooed Cheikha) assumed a position at the forefront. The former was orphaned at a young age, compelled to join a disreputable travelling troupe to survive. Working as a barmaid between performances, her stage name came from the French ‘remettez’ – ‘give me another (drink).’ Her coarse voice exudes a somewhat roughened elegance as she sings of a hymen tearing as a girl runs away to lose her virginity, or “People adore God, but I adore beer” and “When he embraces me, he pricks me like a snake.” Before each song, the Cheikha said ‘errayy’ – my opinion, now transliterated into ‘Raï’.

It was these musical traditions that formed an embryonic stage for Raï. The Cheikhs who straddled the ages, and the Cheikhat who straddled the periphery of both urban and rural life: both brought word to mouth, the suffering ails and folklore of the lumpen. Even though this development was restricted to Oran, heavyweights Cheikh Hamada and Cheikha Rimitti both found themselves promoted by French cultural institutions who sought to curry favour with the Algerian population. Nonetheless, when the Algerian War broke out, they made little secret of their sympathies with the cause of independence. For it was their people fighting, and the cosmopolitan Oran that had treated them so strangely was now blown away into sectarian and Settler violence.

And in the embers of that violence, a new nation emerged – bloodied yet brimming with optimism. Algeria was the canvas on which the hopes and ambitions of a new generation of thinkers, intellectuals and its masses could be projected. But like the late Fanon, those dreams remained unrealised. And so Raï became music for a nation of dreams, prematurely woken.∎

Words by Zaid Magdub.