Beer is Arab, but whiskey is European: Part II

Part I of this essay can be viewed here.

In 1954, Cheikha Rimitti released ‘Charrak Gattah,’ meaning ‘tear and sever.’ In a rich Oranois accent, she instructs a virgin girl to lose her virginity, tear her hymen. All performed to the wooden seduction of the Gasba flute, a fleeting sound that captures both the sensuality and violence Rimitti sings of. Her tone is solemn, maybe even apathetic. It is almost as if she is instructing a soldier off to war:

“Tear, lacerate / Tear, sever / Rimitti will mend / Let’s caress under the covers / somersault over somersault / I’ll give my love everything he wants.”

That same year, the Algerian war of independence broke out, initiating a prolonged laceration of the colonial umbilical cord. An experience that would inform the optimism of a generation of intellectuals and theorists—including Frantz Fanon—as the image of an enlightened empire was brutally deflowered, and the notion of an ideal, post-colonial Algeria was brought to maturity.

The Algeria of independence was not the utopia that quixotic writings of those like Fanon had wished for. Governance was not vested in the people, instead in Le Pouvoir—‘The Power’. A top-down state was created dominated by the army, intelligence services, and several informal factions. The early days of this independence saw the violence of the war turned inwards through purges and the suppression of revolt in regions such as Kabylia. The supreme arbiter of this system, President Houari Boumediene, was a military man of rural, conservative, and religious education. His brand of politics had a sense of machismo about it, one that held a vision of a socialism that was Algerian in its character, and a vision of Algeria that was both Arab and Islamic. A political vision that venerated the elegance of classical and formal Arabic rather than the raw patois of the local dialect, and an Islam that was somehow both traditional and revolutionary.

In pursuit of a new cultural agenda, the regime strongly supported the promotion of Andalusi music, a mediaeval genre that had remained the monopoly of the urban notables and the elite. The elegance of Andalusi Arabic was part of the broader Arabization agenda that sought to unravel the remnants of French colonialism. The pop music of Egypt and Lebanon—known for its adaptations of mediaeval poems and its nationalist fervor—performed by divas like Fairouz and Umm Kulthum, and the bedoui music of the Cheikhs, were promoted in state media. The latter seen to be a refined and higher form of folklore.

The losers in the equation were the Cheikhat. A newly emboldened Ministry of Religious Affairs sought to reconcile the spirit of independence and social revolution with traditional morality. They saw the re-moralisation of society as a revolutionary aim, a duty of respect to the martyrs of national liberation. With the curbing of festivals for saints, bans on the sale of alcohol and radio censorship, the wedding was one of the few spaces where Cheikhat could express themselves.

In the heartland of the Cheikhat, the long suffering Oranois, many musical influences that had been bubbling since the interwar period were beginning to materialise into new sonic directions. The influx of Flamenco and Passacaglia from Spanish settlers and colonial holdings in Morocco, Egyptian music’s hegemony in the Arab World, Jazz and Swing from the American troops stationed in Oran, and the import of modern musical interests mixed with indigenous sounds like Malhun, Gnawa, Andalusi and the neo-folk revival in neighbouring Morocco in the crucible of Oran’s burgeoning art scene. What solidified was a new sound known as Wahrani. Though it remains a separate genre to Raï, it bespoke a generation of musical innovators,often themselves reared with French musical educations. The trajectory of sonic development corresponded with state economic policy, a period of attempted modernisation by French-speaking ‘experts’ in search of revolution. If the interwar period had sired Raï in an auditory womb, the post-war period would create the conditions for its birth.

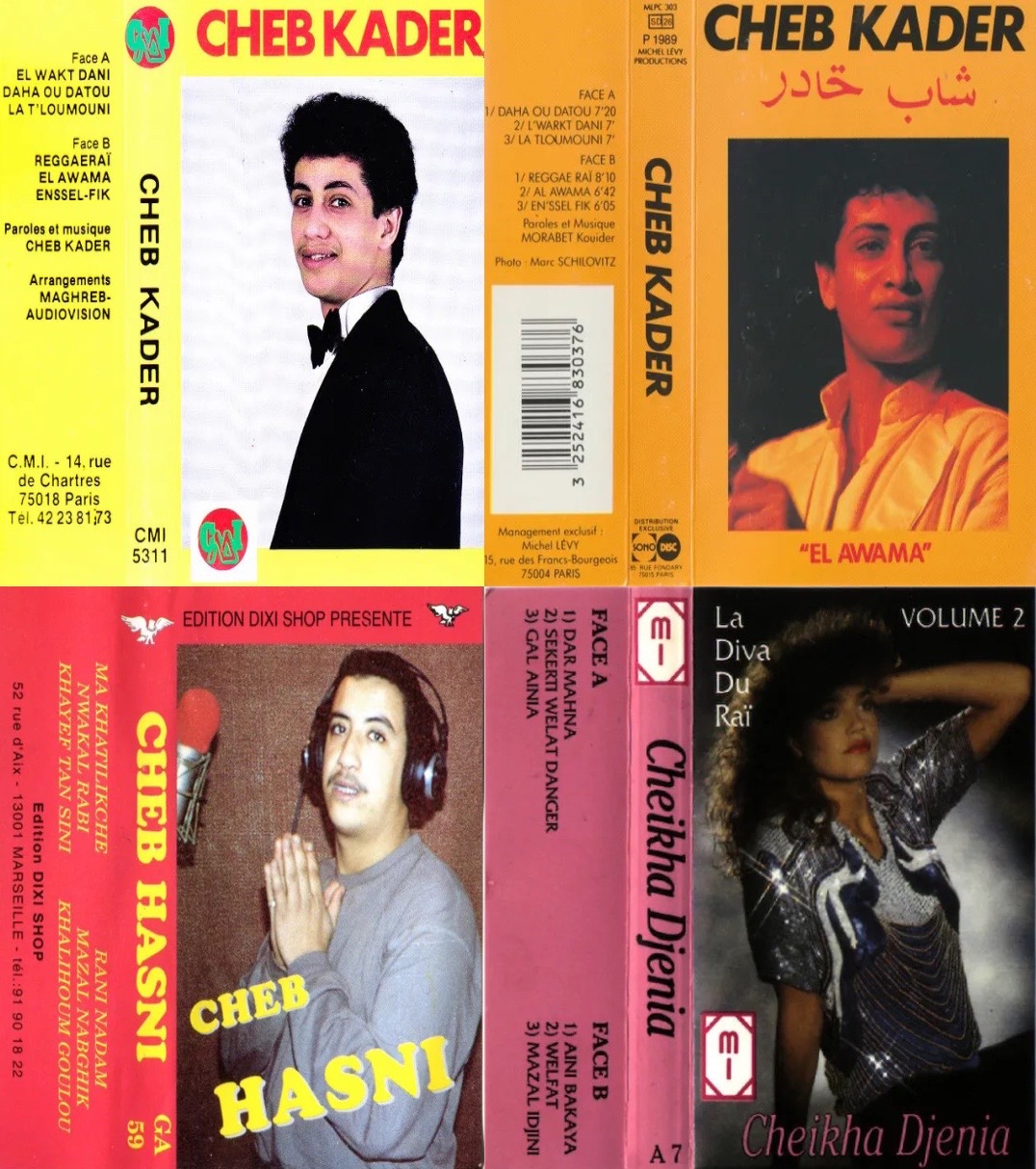

By marginalising the Cheikhat, the regime had paved the way for young men like Belkacem Boutedjla, Younes Benfissa, Boutaïba Sghir and Messaoud Bellemou to assume the mantle. In addition to professional ensembles like Group El Azhar. Working within the melting pot of sound they had access to, they would draw upon the discographies of local Cheikhs and Cheikhat, creating dynamic new covers of their songs. These innovators would infuse a new rhythm and aesthetic to their music, sauteing the raw gospel of their voices with new instruments that sometimes accompanied the gasba and sometimes substituted in favour of new explosive flavours of sound. The product was the Pop Raï of the seventies, still rough around the edges, uncompromising in its lyrics—but groovier and richer with homages to the Blues, Rock and even Cuban rhythms.

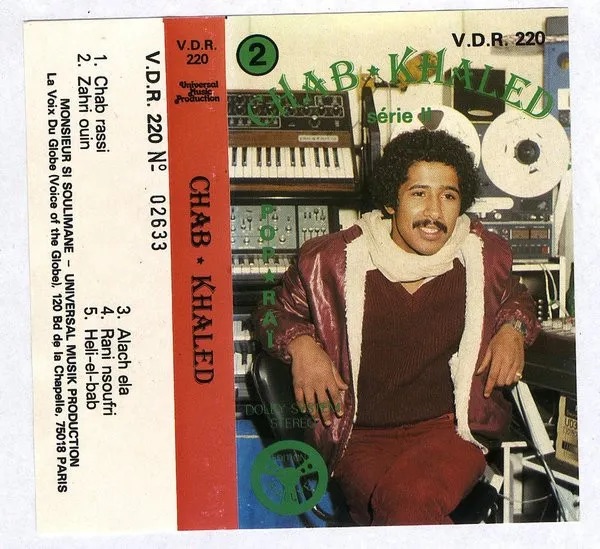

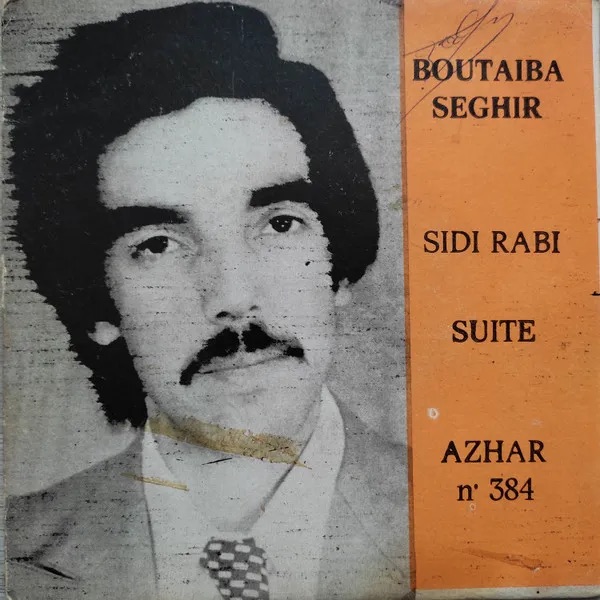

No longer just the earthy ails of the country, Raï would soon become the most popular form of music in Algeria. Elevated into popular consciousness by Cheba Fadela’s 1979 hit Ana Ma H’lali Ennoum (Sleep doesn’t matter to me anymore), which became a nationwide sensation with its opening line: ‘Beer is Arab, but whiskey is European.’ The budding generation of Raï singers sought to distinguish themselves through their youth, adopting the stage as cheb (young man) or cheba (young woman). Their medium was the cassette; their stages the Cabarets and the weddings; and their audiences the men of the popular masses—Fanon’s wretched lumpen. This eclectic band of intellectuals, with their chic Western clothes and nasal male voices expressed a worldview of love, unrequited desire and social dissatisfaction; where each verse told its own story, so that a song could start with a praise of God, his Apostle and his saints, and then immediately become an elegy to the pleasures of the bottle.

The Raï of the late seventies and eighties was firmly rooted in the failures of Le Pouvoir, where a rot ran deep defined by endemic corruption, maligned state industries and chronic unemployment. An explosion in population growth and massive emigration from the countryside to the cities, created a terminal housing crisis that founded ghettos in the place of suburbs. Millions were out of school, and although the regime had encouraged and venerated study in Arabic, those who did found themselves struggling to find jobs in a French-speaking technocracy. Cinemas, theatres and other cultural spaces were practically non-existent. The hittiste—a neologism for men who lean up on walls all day with nothing to do – became a generic feature of the Algerian city. The Raï icons of the eighties often came from this underclass themselves, and just as the Cheikhs gave voice to the nostalgia for life before the colony; and the Cheikhat, the suffering of the colony; the Chebs and Chebbat gave voice to the life and suffering of after the colony.

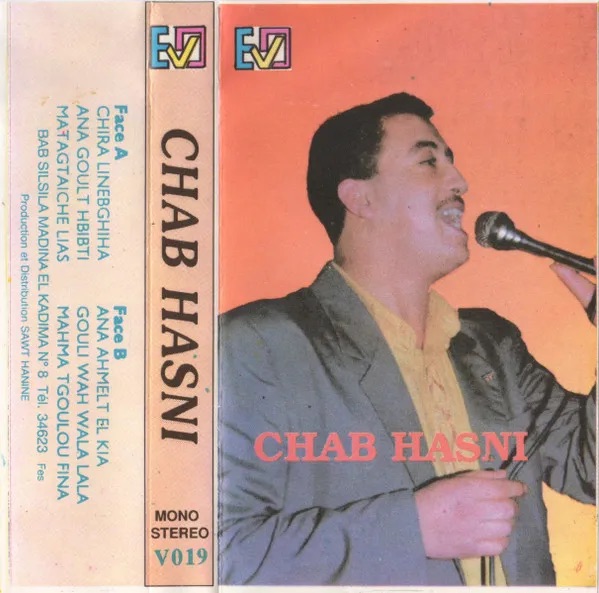

The music of Cheb Khaled, Cheb Hasni and Cheba Zahouania provided an outlet for these young men, with risqué lyricssometimes seen to be inappropriate for the family sphere. Even in the run down districts—where social malaise had set in—families remained a conservative space, not one necessarily associated with leisure or hedonism. So while Raï was in no doubt very popular with women, and incredibly popular at family weddings, it developed an association with the particularly male-dominated spaces of the cabarets. Here, the men could find leisure outside the family, in lyrics centered around their concerns—particularly around women, power and consumption. Raï was not a revolt against the family, traditional values, or Islam, but rather the verbalisation of masculinity’s tensions.

The lucrative nature of Raï was soon realised by local bourgeoise and liberal elements in the regime, who sought to co-opt the genre. A genre that by the late eighties, under the influence of producers like Rachid Baba, was becoming increasingly defined by its electric groove, its erotic fusion of the gasba and synthesisers, and the fetishisation of foreign White women. As much as the era was defined by the soulful woes of love rats like Cheb Hasni (and his love for blondes over brunettes), the late eighties also marked the point in which Algeria collapsed into a carnival of the most brutal, most reprehensible violence.

By the nineties, a combination of political intrigue, popular uprising and brutal repression meant that Algeria would be wrecked by civil war—positioned between a regime that had exhausted popular legitimacy, and a messy constellation of Islamist militants of varying ideologies and strategies. In between them were the masses of Algeria, a countryside left seeping with blood, the depressed suburbs turned battlefields, and the constant question: ‘Who is killing who?’ The tumour of violence, once monopolised by the regime, had now metastasised into the daily lives of the lumpen—the intellectuals of Raï were thrust into a most awkward position. While some performers had distanced themselves from the lumpen riots of 1988, many rioters had taken Cheb Mami’s ‘El Harba Wayn’ (Where to Flee) as an anthem. Later, these hittistes would form a bulk of the electorate that supported the FIS —Front of Islamic Salvation. Many voted for the FIS simply as a means of protesting against Le Povouir. But the overlap between Raï’s heartlands and the growth of political Islamism was a thin line to tow. While many artists identified with the FIS or simply remained apolitical,there remained ideologues who saw Raï at best as a moral degeneration to be restricted, at worst an affliction that violence must cure.

Oran, the birthplace of Raï, would see public concerts banned by the FIS in 1990, as a febrile environment set in. Some artists like Cheb Hasni and Cheba Fadela would criticise the situation, but found themselves increasingly subdued by a growing trend of Algerian intellectuals murdered in the streets. Later on, as the Islamist insurgencies broke out, the same economically ravaged neighbourhoods where Raï had been so popular, would turn into fertile areas for militant recruitment. These communities were already conservative, and some within them, who would later be radicalised by state repression, had found the mosque as an alternate space for their politics, having been excluded from everywhere else;.thers found allure in becoming the mountain outcasts that dominated the rural mythology of their grandparents, captivated bythe imagery of the struggle for independence. Some were fuelled by the local and criminal interests that had come to dominate their roiling estates, now deliberately deprived of services and law enforcement. The Raï of the nineties attempted to understand the paths of the youth, between the mosque and the West, expressing concern for those who had taken neither path. But the bloodied collapse of order compelled many artists to relocate abroad. Cheb Hasni did not. Shot in the face in 1994, he would never sing of his lover again. But he was just one, just one man, one lover compared to entire villages massacred.

The nineties were not all gloom for Raï as an art form. Many performers relocated to France, where, in the face of an upsurge of racism against the Beurs—North African immigrants—Raï became an aegis of identity and solidarity. From France, Cheb Khaled and Cheb Mami would enjoy a brief run of massive successes on the international stage, furthering a genuine excitement that Raï may one day become an international phenomenon of the likes of Reggae.

By the noughties, this was clearly not going to materialise.Yet, the genre soon found resonance among the youth of neighbouring North African countries, with their own potent afflictions and severe alienation from their respective regimes. While the genre has evolved sonically,with the use of an almost jarring amount of autotune, high tempo and drums,much of the lyrical content is similar to that of the eighties and nineties, with less emphasis on the sentimentality of love, and more on pressing social matters, such as the afflicitions of the harraga: the burned ones, illegal North African immigrants whose skin would burn crossing the sea. The shared experiences of the lumpen of these countries, through exclusion and deprivation, has turned Raï into the anthem of the youth once more.

Algeria has largely recovered from the civil war, but it was a recovery characterised by IMF restructuring and neoliberal reform. The Algeria of today is a state sustained through informal power networks and patronage, ruled by a geriatric fragmented Le Pouvoir, whose legacy will remain chronic poverty, absurd levels of class divide and a population demobilised and disgusted with the business of politics. Fanon’s quixotic vision has not been realised. But hiswritings may still apply. He wrote of how natives still grappling with the alienation of colonialism would enter intricate dances in “the form of a muscular orgy in which the most acute aggressivity and the most impelling violence are canalized, transformed, and conjured away.” Perhaps, Raï is this muscular orgy, occurring where decolonisation has failed.

And if Fanon is to be believed, these lumpen are like “a horde of rats; you may kick them and throw stones at them, but despite your efforts they’ll go on gnawing at the roots of the tree.” Perhaps, they’ll be listening to Raï when they do.∎

Words by Zaid Magdub.