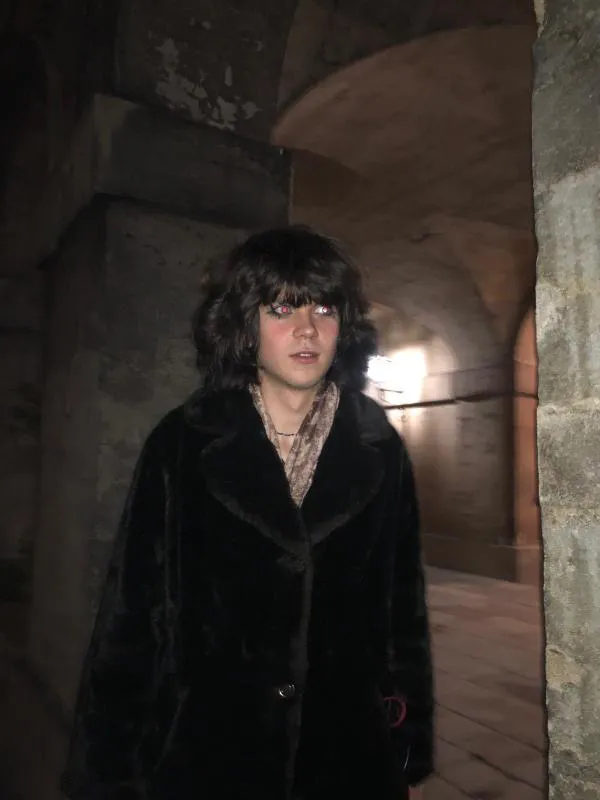

Icon of the Week: Oliver Guilfoyle

Oliver will be a familiar face for anyone who has been to the open jam sessions at the Mad Hatter on a Wednesday evening. Previously the secretary of the University Jazz Society, they are now practically the house pianist of the Oxford bar. But they don’t flaunt it: as I met Oliver at their college, they were relaxed and friendly (my attempt to small talk by bringing up impending finals left them unflustered). And I couldn’t help but notice their vibrant Jazz Society socks—quietly representing. I later agreed when they suggested that “it’s easier to describe jazz in terms of vibes.”

Oliver’s journey into jazz was a typical one: classical piano lessons as a kid, followed by the increasing desire for more scope for expression—by 18, it was all jazz. And they’ve stayed committed. When I met up with Oliver, I remarked on their relatively small room (more tactless small talk on my part). Nonetheless, one thing was clear: space for a keyboard was non-negotiable.

Settling down, I ask Oliver about their time as the Jazz Society secretary, specifically what it’s like running the (open, buzzing, well-attended) jams at the Mad Hatter. “There’s two criteria” they explain, “make the music good and make it accessible for people to play. And the easiest way to do that is to play something groovy and funky.” That approach might explain why those jams constitute a rare opportunity to engage in something genuinely communal and exciting, with people you probably don’t even know. But Oliver’s role entailed a lot of publicity work too. I wondered if those sorts of tasks—Instagram posts and advertising term cards—invoked any thoughts about making jazz more popular. “Not really,” they answered, more importantly, “the thing you want to avoid is people who want to be there, not being there.”

Beyond their time in the Mad Hatter, Oliver is part of a few bands too. Most of their focus is currently on 6 Lane Overpass, a newly formed jazz-hop band. I wondered if that particular combination of genres was one that interested Oliver. They were reluctant to commit to any one sub-genre, but acid jazz and electronic jazz fusion got a mention. As for influences? McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, Roy Hargrove—not much to argue with there.

But this was not the end of it. Oliver explained how Keytones, another band they’re part of, resembles something more akin to a conventional (albeit small) big band. Ah! Something a bit more danceable, I rushed to respond (I had earlier posed the annoying question of whether jazz is dance music). Oliver conveys their delight for the times when people get up and dance at the Mad Hatter jams. Often that’s just because the music is more rhythmically consistent and harmonically obvious: “Sometimes it’s fun to play the right notes!”

In fact, there are plenty of student bands around, Oliver explains while listing a few of them. “The Oxford music scene is freaky,” they argue, since there are just so many students who want an audience to play to. The problem, then, is the lack of reciprocity. “I feel like Oxford is a pretty good reflection of how jazz is perceived generally. There’s these two ways: there’s the cocktail bar jazz and there’s the fact that jazz has influenced popular music, directly or indirectly.” Lots of people don’t seem to (want to) recognise the latter, however, leaving the number of willing listeners for the groovy genre-crossing jazz dwindling. Oliver proposed one solution: forgetting all the typical bases and understandings which define Western music. “I love intellectualising jazz; I love music theory,” they admitted. But also, when you let go, “audience members find that fun.”

So, in between discussing the supply and demand of music in Oxford and the varying danceability of sub-genres, we got onto music theory. We skimmed through the oft-invoked debates around music theory: is music only subjective? Is Western theory mathematically justified? The conclusion: “It’s all bullshit. Jazz is bullshit.” (Oliver insisted that this was meant endearingly.) Actually, their dismissal was rather more sophisticated: “It’s cultural…what you expect to hear is completely culturally informed, because it’s completely informed by the music you’ve heard before.”

Underpinning our whole conversation was a slight self-consciousness. We both agreed that talking about jazz can always be a little ostentatious. “Everything you say about jazz is pretentious,” Oliver suggested with the mildest of ironies. I asked why they thought that was the case. Oliver threw around some ideas about elitism and taboo: “Jazz started off as a grass-roots thing, and is now in the process of transitioning into the kind of culture that is built around music that’s extremely old.”

“Jazz musicians are so good at getting things wrong,” Oliver said. “As I started playing jazz, I stopped being afraid of getting things wrong.” We lamented: perhaps that’s why people don’t dance enough in this country, they’re all afraid of getting it wrong. “The thing that makes jazz seem inaccessible is the people who don’t know jazz don’t see that we’re the masters of imposter syndrome.” Still, the door is always there. “Jazz is an open window…it’s on you to jump out.”