The campus novel on vacation

The first thing I did after finishing my exams last May was read Elif Batuman’s quintessential campus novel The Idiot. Although I was checking out of academia for the summer months, I couldn’t help but return to its comforting rhythm in Batuman’s book, which narrates Selin’s freshman year at Harvard. I read the novel when I first arrived in Oxford, where I came by chance, not to take classes or even really work a job, but to… live? I felt, as Selin says in Batuman’s sequel, Either/Or, a bit as though I had “lost the thread of the story I was telling myself—the thread of the story about my own life”. Halfway through my undergrad degree, coming to Oxford for reasons that felt, at the time, unknown to me, the story of a girl who reads to narrate her own life was just what I needed.

After I devoured Either/Or, I dove head-first into the genre broadly dubbed the “campus novel”, looking for answers. Answers to what exactly? I wasn’t sure. After Batuman, I went for Evelyn Waugh’s Oxford novel, Brideshead Revisited. Reading about Charles Ryder’s uneasy assimilation into college life, I leaned into my discomfort with the liminal place I occupied here — not an Oxford student, but not a local either. Turning my gaze homeward, I read Stay True, Hua Hsu’s campus memoir about Berkeley in the 1990s; I commiserated with Hsu’s description of the broken elevator in the dorm where we had both lived and visualized him tutoring writing in the same center where I’d worked the previous spring. The mirroring I experienced reading these books went beyond the literal. As I explored the genre, trying to place my own life within the plots and tropes of each book, I realized that this very process of self-reflection is a core tenet of the campus novel. As I read about Selin reading voraciously to understand her life, I found myself doing the same.

While I ended up reading books about reading, the novels took care to clarify that little learning takes place in the classroom. Brideshead doesn’t claim to be about academics at all—Charles spends his first few terms learning which wines pair best with strawberries (“Château Peyraguey”), and when to wear a top hat (always on Sundays, his father says). When the novels depict classroom learning, they question its value and ruthlessly satirise. In Either/Or Selin recognizes the “professor’s characteristic pleasure at withholding information”, and in Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Marriage Plot protagonist Madeleine Hanna observes that rather than leading the class, her professor “observes it from behind the one-way mirror of his opaque personality”. What passes for teaching might better be described as failed communication.

Yet the campus novel is not anti-intellectual: effective and intriguing communication is portrayed as heavily metatextual. Life is worth living when it is mediated by books and ideas, the novels suggest over and over. As one pretentious student in The Marriage Plot puts it: “books aren’t about ‘real life’. Books are about other books”. Batuman’s books are about books and real life though. Her characters see themselves in the books they read, as life and literature become inextricable. Eric Naiman, who teaches a course on “university fictions” at the University of California, Berkeley, says Batuman’s novels are structured around complex “double plotting”, in which events of Selin’s life are braided together with her reading. One of the assignments in Naiman’s course is the “Batuman project”, in which students write their own piece of double-plotted creative writing.

In my uncertain summer, I could have used some double plotting of my own. Having ended up in Oxford primarily because my parents moved there, I felt some pressure to answer the perennial question: why was I there? I wanted to know what purpose this time, or for that matter any time, was serving in the grander “plot” of my life. Perhaps it should have become clear to be when I began conceptualising life as a literary plot that I had spent too much time pondering. Defaulting to campus novels, in which characters progress through their education at various elite institutions, gave me the false sense of security I needed. Perhaps the same security that classes give me during the year, or that books give Selin.

The kind of reading Batuman imagines for Selin is appallingly self-absorbed, but also somehow enviable and exhilarating. She is constantly experiencing intense visceral reactions while reading—a line in The Picture of Dorian Gray prompts “a lurch of dishonor”, and she “almost [throws] up” while reading Kierkegaard’s “Seducer’s Diary”. André Breton’s Nadja captivates her so completely that all she wants to do is to write down everything in the novel that resonates with her. She essentially rewrites Breton in her own image:

“I started to keep a running record in my notebook of everything in Nadja that seemed related to any of my problems… I wished I could write a book like that about Nadja, where I could explain each line, and how it applied in such a specific way to things that had happened in my life. I knew that nobody would want to read such a book; people would die of boredom.”

Selin chooses a list: a disjointed form lacking the structure and sequence of a novel or an essay, less cohesive and more spontaneous. Rather than borrowing from any recognizable literary criticism, Selin proposes a form of novel-reading that focuses simply on the ways what happens in the novel mimic what happens to her.

Batuman’s novels seemed to invite a similar mode of receptive reading. When I finished The Idiot, I immediately forced the book on the two friends I was traveling with. In my—now our—copy of the book, we annotated on top of one another. We wrote “lol” and “!!!” more than anything else, but some pages are full of colour, where we aggressively underlined the same quotes. We wrote each other’s names, those of people we knew, of films and books and directors and writers evoked by specific scenes or lines. Next to a paragraph describing a book annotated by somebody else (who “had systemically underlined what seemed to be the most meaningless and disconnected sentences”) one of us had written “US!”. Our notes mirror Selin’s Nadja list — they’re not organized, or hierarchical, and they don’t easily yield insight. Mostly, they react and relate and exclaim and enthuse. We read The Idiot the way Selin reads in The Idiot. We filtered the text through our own experiences, and we communicated through the novel.

After cannibalizing her favourite books to create her own narrative, Selin vows at the end of Either/Or that “from this point on my life would be as coherent and meaningful as my favourite books”. Simultaneously yet contradictorily, she feels “a powerful sense of having escaped something: of having finally stepped outside the script”. My summer of reading the campus novel, of reading about reading, and of questioning my place in both arenas likewise eventually set me free. While in Oxford I couldn’t help but wonder. Was the guy who took me to the opera in London my equivalent of Selin’s Turkish summer fling? Would the spontaneous visit from a girl I met on LinkedIn change my life forever? Would my chance encounters in Port Meadow? Everything could be imbued with meaning, or not. Yet it was only when I returned to school in the fall that I — like Selin before her own third year of university — let go of the plot and felt that my life really began. Maybe it was in jumps and starts, more akin to Selin’s list of resonances with Nadja or our annotations of The Idiot than to the arc of a great novel. And maybe that’s also why reading to make sense of life is both all we can do and absolutely futile.

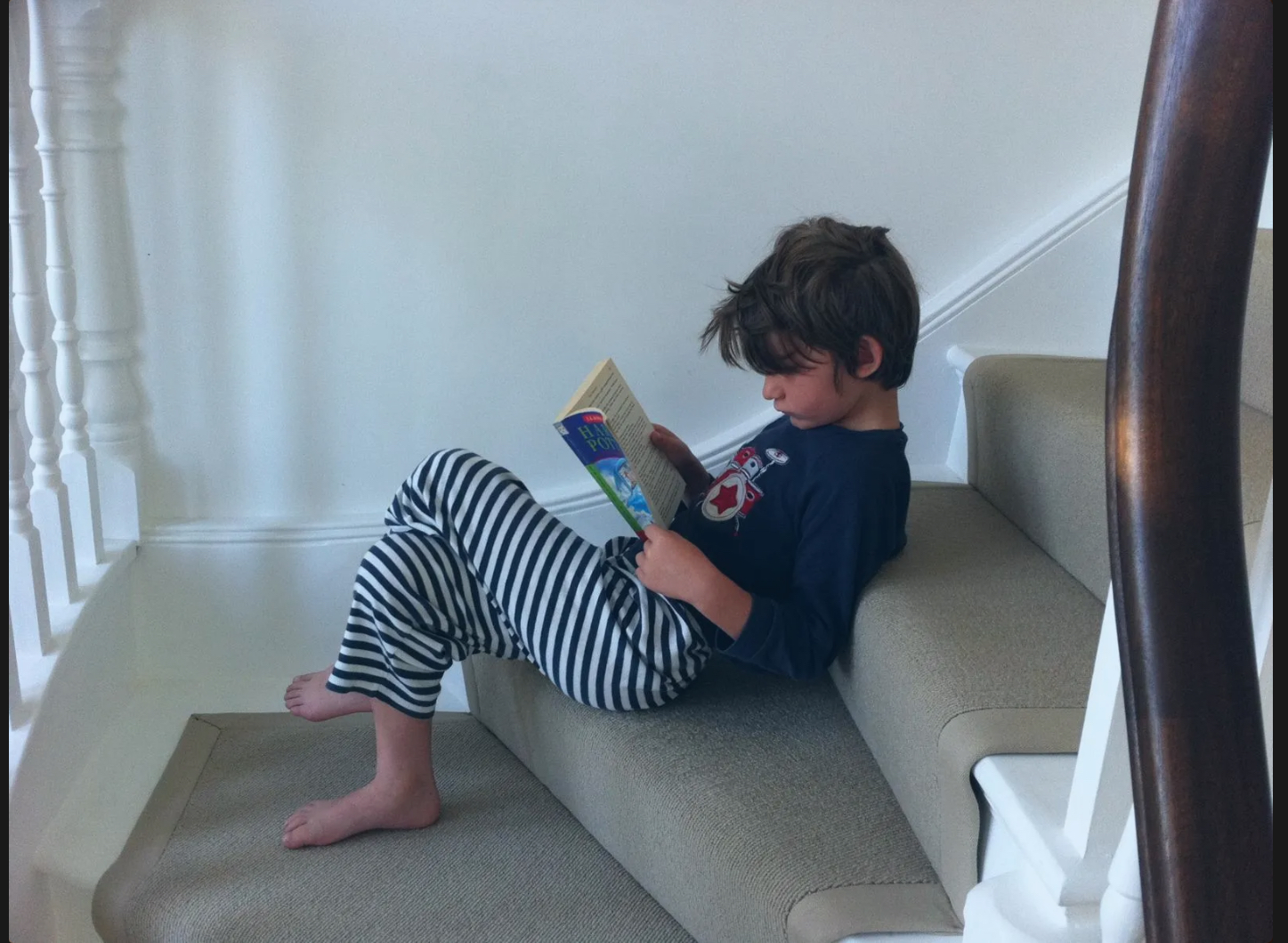

Words by Clara Brownstein. Image courtesy of Clara Brownstein.