Prizes

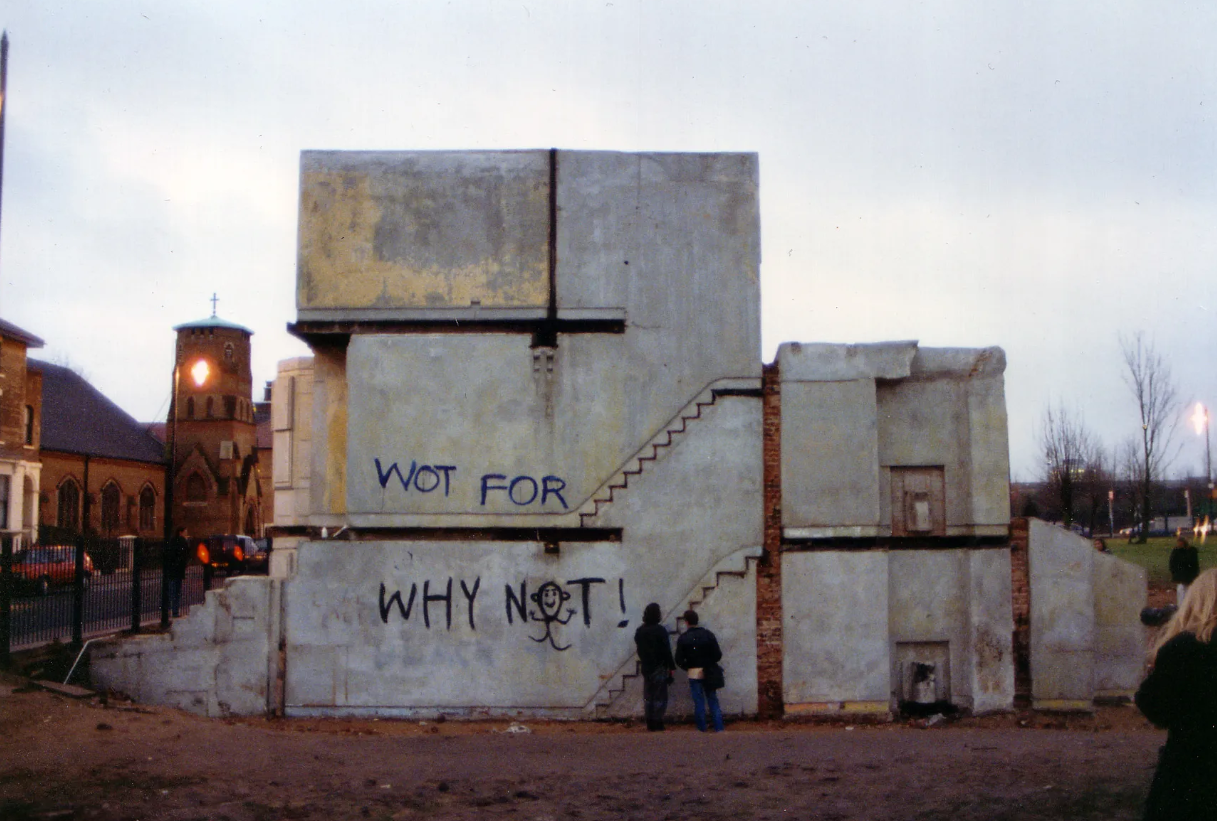

In 1993, Rachel Whiteread won the Turner Prize for House, a concrete cast of the interior of a terraced house in Bow, East London. The piece was exhibited where the house had once stood, and it was praised widely by critics, who were entranced by the uncanny mix of presence and absence the sculpture gave rise to. The concrete stood alone after the demolition of the houses surrounding it: interior became exterior, and what was once airy domestic space became the road’s sole solid reminder of the terrace as a now eclipsed urban form. The same day that Whiteread was announced the prize’s winner, the local council voted against extending the run of the temporary sculpture, arranging for its demolition in the subsequent weeks. Eric Flounders, the council chair, had described the piece as a monstrosity, and claimed any support for it came from middle-class districts beyond his council’s jurisdiction. The prize ceremony was televised on Channel 4 that evening, during which adverts from the K Foundation, a project set up to spend the income of 80s electronic duo The KLF, announced their parallel award for “the worst artist of the year”. That prize, carrying twice the monetary value, had the same shortlist as the Turner, and, in the end, the same winner.

Initially, Whiteread did not accept the K Foundation money. When she was informed that the alternative was the cash being burned, she accepted the prize and split it between grants for young artists and a donation to Shelter, the homelessness charity. The sculpture continued to spark debate. A first piece of graffiti on the house, asking “Wot for”, had attracted an equally succinct reply: “Why not!” Whiteread attended the demolition, but resolved only to cry once the deed had been done and the gathered press moved on. Not that crying would have inspired much sympathy: the sculpture’s last rites were administered by Joe Cullen, the man who bulldozed it, pronouncing “It’s not art, it’s a lump of concrete.” Nor did Whiteread’s acquiescence to the K Foundation prevent any cash going up in flames. 1994 saw the execution of the performance art piece K Foundation Burn a Million Quid, which is exactly what they did. A penny for the thoughts of Messrs Flounders and Cullen.

Looked back on now, the events surrounding the 1993 Turner make for a pretty accurate sketch of the goings on in ’90s British art more generally. From public opposition to the ostensible extravagances of the YBAs, to money flowing in that long gone ’90s fashion, the prize now stands as a capsule for the era, and the artists, that it judged. And so it should. If the prize represents the pinnacle of contemporary British art, then you’d hope, over time, the winners reflect the contours of British art’s development. At the same time, though, the Turner arguably missed the two exhibits which best survive in our collective memory of the YBAs. Damien Hirst’s shark and Tracey Emin’s bed were both shortlisted, but neither got the judges’ nod in the end. Hirst would go on to win the prize two years later for a different animal-in-formaldehyde concoction, but that only serves to prove the point. Prizes do what they can to reflect the forms and pressures of their time, and they can give you a good summary when looking back, but they are also inevitably one step behind. The established institutions of a cultural form can never keep up with that form’s cutting edge, because that’s basically what defines a cutting edge. It’s a story as old, at least, as the Salon de Refusés.

There are other problems, too, with prizes. For one thing, a prize by nature flattens the diversity of practice that exists within a given form. Supposing that you can select a “best” instance art, music, or whatever in any given year is a bit like supposing you can select that year’s funniest joke, or its most perfectly shaped fruit. You can try, but faced with such a range of options—especially if you value, as so many of these prizes do, “pushing the boundaries”—you end up comparing apples and oranges. Take this year’s Stirling prize as an example. Britain’s premier architectural prize went to the Elizabeth Line. Even if you set aside the fact that the project was about five years delayed, went massively over budget, and, in Sadiq Khan’s words, “has not met the consistently high standard” expected of it, it’s hard not to feel slightly sorry for the other shortlisted constructions. Wraxall Yard, one such nominee, is a disused dairy farm converted into a community centre and adjoining holiday home. Acclaim focuses on its groundbreaking standards of accessibility, made all the more impressive by its rural setting. The official line for the Stirling Prize is that it is awarded to “the architects of the building that has made the greatest contribution to the evolution of architecture in the past year”. One wonders how exactly the judges decided on these terms when faced with projects of such varying magnitude, and more to the point, whether the Lizzy Line is even a building.

But even when it is possible to get the judging right, these events still aren’t beyond reproach. A key attraction of these prizes is that they offer some glitz and glam, and hopefully some money, to areas of culture where this is somewhat lacking. But all of that needs sponsors, which can get difficult. This year’s Mercury Prize went to English Teacher. The Leeds post-punk act gave the standard oh-my-God-we-never-expected-this-but-here’s-a-list-of-everyone-we-need-to-thank speech. As endearing as the band seemed, this registered as a particularly rambling attempt at that genre. The reason for this, I think, is that there was no audience at the event. The only people around to offer applause were the entourages of the acts English Teacher had beaten. So, instead of the band’s momentary stunned silences being punctuated by cheers from attendees just happy to witness the event, the speech received mainly they-seem-like-lovely-people-and-I’m-sure-they-deserve-it-but-I-wish-my-friends-had-won whoops. The ceremony was so stripped back because the prize’s sponsorship deal with Freenow, a taxi company, had come to an end and no new commercial partner had been secured. But getting a sponsorship is really a dammed if you do and damned if you don’t situation. This year’s Turner Prize exhibition features four adjacent television screens placed at the gallery’s entrance. Each plays a video on loop profiling one of the four artists nominated. The profiles are remarkably well-made, giving a good sense of the lives of the artists without sinking to the kinds of sentimentality that usually accompany these things. Delaine Le Bas goes to Glastonbury and, with the help of a construction-standard scissor lift, paints a wall that must be more than five times her height, improvising the whole thing. Pio Abad, whose nominated exhibition focused on the colonial history of the Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, recalls finding out that his flat, at the Royal Arsenal Stores, had been the site of British Army training before the pillaging of Benin. He says that his work “goes back to the fantasies of capitalism, the fantasies that we’re all implicated in.” As if to prove the point, the film loops back to the start, and opens with clean white text superimposed onto shots of his home: “A film supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies”.

The media surrounding the prizes is not only of note in the case of the Turner. The Booker Prize was televised by the BBC from 1981 until 2019, and watching the old coverage (thankfully preserved on the Booker Prize’s YouTube channel) can make for interesting viewing. The BBC’s old format was centred on a studio panel of literary authorities—academics, editors, novelists—who discuss and debate the merits and demerits of the shortlisted books, with the cameras shifting to the actual ceremony just in time for the announcement of the winner and subsequent acceptance speech. The presenters punctuate the show with great lines like: “In Guildhall now they are settled into their main course, so, while they work their way through saddle of English lamb en croûte, we sip our mineral water and do our own judging here.” After the winner has their moment in the limelight, the last word goes back to the studio, who are often not at all pleased. Germaine Greer, a fellow in English at Newnham College, Cambridge made famous by her 1970 second-wave feminist opus The Female Eunuch, was a regular on these panels, and always offered amusingly supercilious final remarks. In 1990, after A.S. Byatt won for Possession, Greer closed with “Congratulations. Well done. Now write a short one.” Byatt’s book had been described earlier in the programme by Eric Griffiths (Trinity College, also Cambridge) as “the kind of novel I’d write if I didn’t know I couldn’t write novels.”

Fast forward to 2018, the BBC’s last year of coverage, and the spirit of democratisation has had its way. The panellists discuss the books live from the Guildhall, and now they stand, rather than sit around a table (whether this is an attempt to make the conversation seem less aloof, or just yet another symptom of BBC cuts is an open question). In place of condescending literati, we now have a vlogger of 30k subscribers fame to analyse the shortlist. On Anna Burns’ Milkman, the prize’s eventual winner, he has this to say: “Initially I struggled with it on the printed page, but once I got the narrative in my ear [with an audiobook] I was with it and I was going through the quirky narration. But what I think is incredible about this novel is that she’s writing about The Troubles, but in a dystopic [sic] way. You feel like ‘oh this could be the future’, but actually it’s already happened, and I think that’s incredible.” The older coverage has not aged perfectly: it is, in moments, rather stuffy. I can’t help but think, though, that along the way from 1990 to 2018 much more has been lost than gained. From 2019, the Booker streamed coverage of the ceremony straight to YouTube, but with increasingly little critical analysis of the books. By 2023, all of two minutes were afforded to the would-be critics (one podcast host and one YouTuber); most of the coverage was taken up by actors’ readings of passages from the shortlist, interviews with those actors, and an infuriatingly anecdote-heavy interview with the previous year’s winner. In 2024, as far as I can tell, there was no supporting coverage, with the only broadcast being a livestream of the ceremony itself. BBC Radio 4 played the audio from the ceremony on Front Row. What the main course was, they didn’t tell us, and no longer can we be treated to some transitional shots of half-eaten plates being worked through.

So prizes have lots of problems. But that’s exactly what makes them interesting. They struggle to adapt to the shifting boundaries of the categories they seek to judge. They evince the tensions between art’s abiding concern with progressive politics and the art world’s longstanding status as a launderer (both literal and reputational) for finance capital. Their coverage brings to the fore the shifts in the media’s relation to cultural artefacts more generally. In all this, the prizes are distilling the currents of 21st Century culture in a bite-sized format. What made Germaine Greer’s pronouncements on the Booker so captivating (and probably, despite her birth, so British) was that she was sceptical about the whole idea of it. The shortlist was, on her account, really just the result of secret deals between publishing houses anyway. The Turner Prize winner will be announced on 3rd December. For what it’s worth, I think Pio Abad, for his substantive and context-specific response to Oxford’s imperial legacies, and Claudette Johnson, for her richly coloured portraits of figures with pregnant stares, would both be deserving winners. A win for Delaine Le Bas or Jasleen Kaur would be giving in to some of the more mindless aspects of contemporary art: Le Bas hails from the hurriedly-scrawled-skulls-and-dollar-signs school of post-Basquiat imitation, Kaur leans into the smaller-delicate-worldly-objects-draped-over-larger-solid-worldly-objects trend which has probably run its course, and both pipe in soundscapes with imports much too obvious to actually have an effect. But, as I have tried to show, what’s really worth caring about isn’t which artist any individual or committee tells you is the best, but what the whole endeavour, as a microcosm of where the culture is heading, shows you. So, whether they pick the winner you wanted, suspected, feared, or had never even heard of, keep an eye on the prizes, and give them their due.∎

Words by Joseph Rodgers. Image Courtesy of Matthew Caldwell.