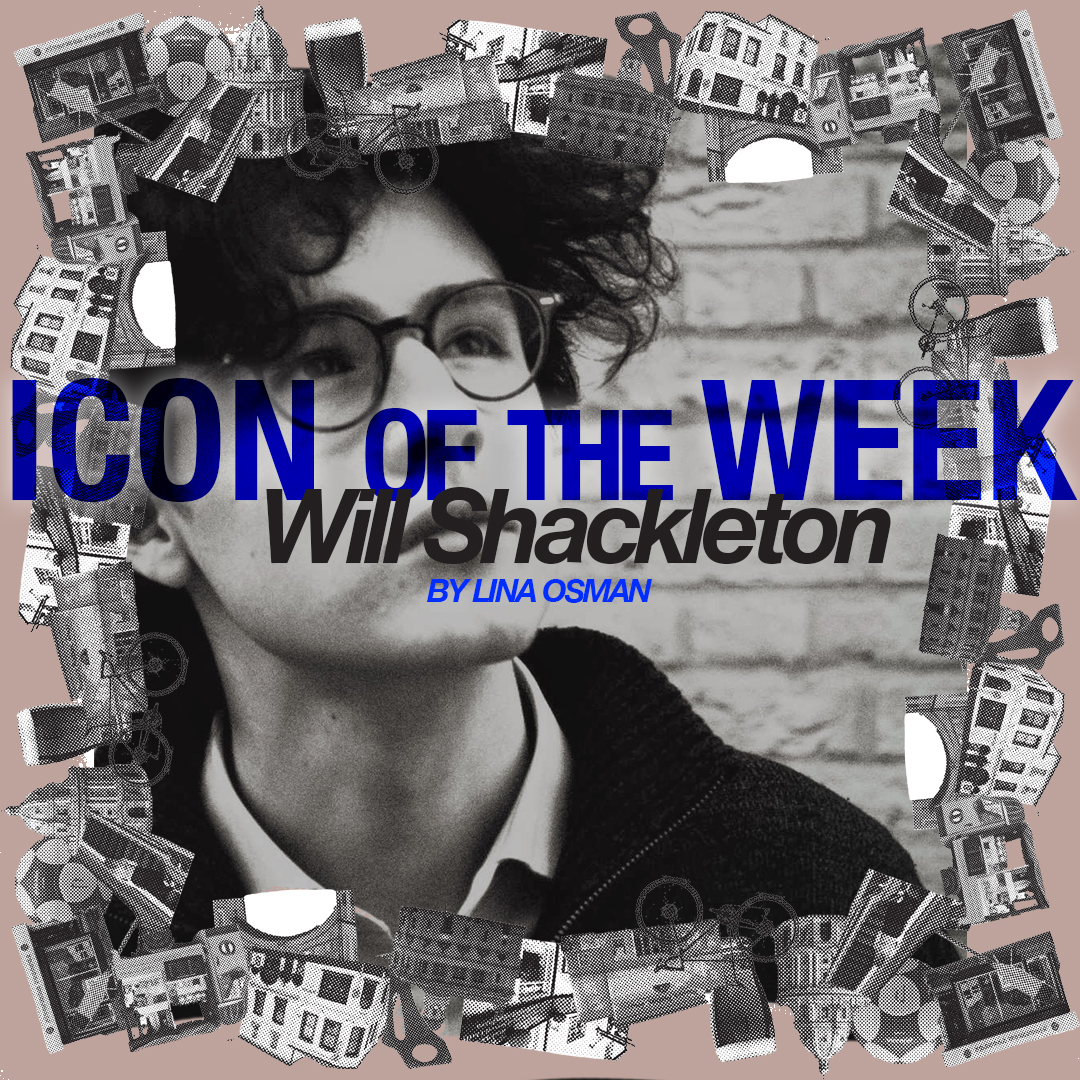

Icon of The Week: Will Shackleton

For the past week, every time I’ve mentioned that I’m writing my Icon of the Week about Will Shackleton, I’ve received one of two responses: “Oh, I love Will Shackleton!” or “Who is Will Shackleton?” With those mixed reactions in mind, I sat down with Will determined to answer that very question: who is Will Shackleton, and why does everyone love him? (Of course, the moment we sat on a bench for our chat, Will was stung by a wasp, which felt like a sign this piece might be doomed from the start.)

You might be surprised that this week’s Icon is a person, rather than a place or organization like the past few have been. But if anyone deserves the title, it’s Will. I first met him last Trinity at a Union dinner we were both guests at, where we were coincidentally seated next to each other. By that time, Will had already made quite a name for himself—he was starring in Two Gentlemen of Verona that term, and a friend working on the show couldn’t stop raving about how lovely he was. That charm was immediately apparent when I met him.

So, who is Will Shackleton? Known by some as the “king of OUDS” or the “face of OUDS” (Oxford University Drama Society), Will has become one of Oxford’s most prominent student actors. He’s starred in three Playhouse productions, countless smaller venues, and numerous fringe performances, making a name for himself across the university’s theatre scene. Will’s love for acting started early—at just three years old, he saw The Snowman in London. Though initially terrified, he was completely captivated. His first role was the highly coveted Bethlehem Star in a nativity play, and he’s been on stage ever since, continuing through school and now at Oxford.

But what makes Will stand out in a place where talented people abound? Part of it is his attitude. Will tells me that the best part of the Oxford theatre scene is its “friendliness and collaboration”. Unlike other universities, where drama scenes are sometimes controlled by tight-knit committees, OUDS allows for a certain freedom—something Will values deeply. There’s room for all kinds of productions, from the big Playhouse shows to ones like The Molly’s whose niche is doing fun parody musicals and Matchbox productions – who do cool, lowkey, slightly dark twisted stories.

This openness has come into question in recent times, however. Recently, OUDS faced a scandal over claims of pre-casting for Dangerous Liaisons, where, allegedly, despite auditions being held, the main actors were already decided by the director. One cast member who has since quit wrote: “Despite objections, I do believe that pre-casting was massively involved in not only my casting but also the vast majority of the actors involved”. When I asked Will about this, he acknowledged the issue but clarified that he’s never felt that roles were decided before auditions in the shows he’s been a part of. “The more shows you do, the more traction you build,” he explains, which might make casting easier for you. “It’s a small world.”

Regarding whether OUDS is generally exclusionary, Will acknowledges that there is an inevitable large presence of students from London private schools, with the proportion being higher than in the general population. However, he notes that this is reflective of the university, rather than unique to OUDS. This trend tends to be more visible in executive positions within the society. Will points out that the issue also stems from the pool of people being limited to those within the university, whereas in the professional industry, casting decisions are made from a much wider range of talent across the country. He says, “more competition will breed more meritocratic casting” in the real world compared to within a university setting.

He suggests that part of the solution may also lie in challenging preconceived notions about who can play certain roles. “Radical” casting choices, he believes, can be exciting and bring something new to the table. While he recognizes that people in prominent positions have a larger responsibility in contributing to wider systemic issues, he believes OUDS, at its best, offers opportunities for everyone—especially when there’s healthy competition: “The secret strength of the society is that it’s not run by a supreme drama leader”. Will admits he’s not particularly well-versed in these discussions, as his role as an actor means he doesn’t often engage directly with casting panels or wider industry debates on the topic.

Despite his status as the “face of OUDS,” Will avoids executive roles, preferring to focus on acting. He explains that being an actor allows him to “just do me” without the heavy responsibility of managing others, unlike committee positions. Still, he sees the potential for even more openness and meritocracy in casting at Oxford, especially if more students get involved.

Now, after a successful run, Will has decided to step back from OUDS to focus on his degree. He dreams of pursuing acting professionally but insists he doesn’t feel pressure to follow in the footsteps of famous Oxford alumni like Hugh Grant. For Will, the goal is simple: to make a living from acting. He reflects on his favourite roles, mentioning Angels in America as his standout experience because the play itself has a lot of subtext and room for an actor to be creative, and he hopes to revisit the role of Louis later in life. He tells me that the most fun he’s had doing a show was the Magdalen Garden play, and less fun, was doing THAT park scene in Angels in front of his parents. Will’s favourite venue is the Playhouse, which is “definitely the nicest one as an actor” but that the “intimacy of the Pilch holds a special place in my heart”.

Will’s favourite play is Rabbit Hole by David Lindsay-Abaire. When it comes to reading plays, he has an interesting take: “Bad plays will read as bad plays, good plays will read as good plays, but great plays often read as bad plays.” He uses Closer by Patrick Marber as an example—on paper, it might seem stilted, but the film adaptation, featuring Natalie Portman and Julia Roberts, does an excellent job of making the play come alive. As for Shakespeare, Will thinks Macbeth is overrated, while Hamlet is treated with such reverence, he loves when productions aren’t afraid of this and have fun with it.

When I ask for advice for aspiring actors, Will suggests diving into the Oxford drama scene without hesitation. “Sign up for random things, meet lots of people,”, also mentioning that he wishes he auditioned for Dr Dysart in Equus. You might not love the first thing you try, but eventually, you’ll find your niche.

So, who is Will Shackleton? He’s an actor, a friend, a guy who loves Arrested Development (but only the first three seasons) and is, like the rest of us, saddened by the price increase at Nando’s (Will was very excited to share his Nando’s order with me: chicken thighs, because they’re more moist than the breast, with medium sauce. He rotates between peas and broccoli for sides but always gets peri-salted chips and garlic sauce and he always opts for water, insisting that paying for the bottomless Coke is a waste). But most of all, Will is someone whose kindness and warmth make him an Icon—whether you’ve heard of him before or not. After spending time with him, I couldn’t help but rave about how genuinely lovely he is. His spirit animal, he tells me, is a butterfly, and I think that’s why everyone loves him. ∎

Words by Lina Osman. Image courtesy of Will Shackleton, and Gruffyd Price.