When grief finds us

I have a friend who lost her father when she was young who has always told me that her favourite book is Grief is a Thing With Feathers. I have never felt the need to read it—I have, luckily, never lost anyone close to me, anyone who has brought grief, with its feathers, to me.

And yet, I spent my eighth birthday in Khartoum, Sudan. My aunts gave me money and the kids at school sang for me in a way that made me feel as if there were no other birthdays in the world. A simple cake made by my mother and a gold bracelet from my grandmother. The thing is, since war broke out on April 15th 2023, the school burned down, the kids died, and the bracelet is gone along with my grandmother’s house. I am grieving mid-July nights where we lay asleep in rows of metal beds in my grandmother’s courtyard, searching for peace, feeling closer to God the more that we felt the cold breeze rock us to sleep. I am grieving seeing my grandmother’s face in Khartoum every summer—slightly older, a new blemish, a smile that mirrors mine, her Black skin slowly beginning to lose pigment. Her face, now in Cairo, is weighed down and plagued by a fear she may never return home.

And yet, I spent months at university unable to speak of Gaza because it felt too close to Khartoum. Because when you’re crying at a vigil and the names are so similar, Gaza becomes Khartoum and Khartoum becomes Bangladesh and Bangladesh becomes Congo and I remember Sonya Massey, and I remember Breonna Taylor and I remember and I remember and I remember.

And yet, when I heard Bay Davis’ performance of For Those Who Know Grief by His First Name, the line “I have never met a woman alive who does not know what it is to be loved and hated by a man in the same sentence” rang through my head for days. I am grieving my trust in men because isn’t it always a man? I am grieving every beautiful city ruined for me by the memory of a man I can no longer speak to. I am grieving my faith in humanity, my own humanity, my sensitivity to death. I turn to writing but it is not lost on me that words are only futile: “I can’t breathe”, “I rebuke you in the name of Jesus”, “I’m so sorry for your loss”.

Grief has never found me with its feathers because, for me, grief has always been collective. When war broke out in Sudan, I may not have lost family members but I lost the life I’d imagined for myself there. I lost my dream of getting married where my parents got married, I lost the chance to be adorned in henna and gold jewellery in the house my mother grew up in, I lost the chance to take my own children back there one day and point at all the places which held the most defining moments of my life. When I watched videos of people being shot, women raped, children starved, Khartoum was no longer beautiful to me—my childhood memories now tainted by the sound of gunfire, loud screams, and final prayers. For weeks, I could not pick up the phone and call my family, figuring that if I avoided the situation, it may just disappear. I could not tell anyone why I was not able to study, why going to school became silly to me, why even friendships felt futile in this state.

On the day my family was escaping Sudan, I could do nothing but sit in bed and cry. In this grief, I could only find comfort in other Sudanese people. It seemed to me like the world was going on for everyone else, and I needed people to understand that my world was disrupted, my world could not go on, my world was escaping a country they had lived in all their lives, crossing borders they have never seen, some of them rejected and left behind. My world had escaped death only to be met with hate in another country.

Watching Palestine or Bangladesh or Congo, I do not lose family members but my heart aches for those families. It aches for the women, like my cousins, who may now consider death an easy option. My heart burns to watch other people’s struggles ignored, to watch my friends fall to silence because sometimes what you need to say is too much, too close to home, too close to tears.

When the riots broke out, I may not have lost any family or friends but I lost the sense of home I was forced to create in a country that had promised me safety. I lost the ability to feel comfortable in the spaces I thought could be mine, I lost the ability to go for walks, to buy groceries, to be in this country and loud and bold and Black. In this chaos, the only community I could find was in other people of colour: in discussing our fear, in pretending it wasn’t happening, in sharing ways to stay safe, praying together, praying for each other, checking in on each other. Texts that ask where each other are, texts that demand an announcement that you are home safe, texts that remind you that you are loved and cared for and there is a home for you here.

For me, grief has always been collective. None of my losses are mine alone, and yet, they are sharply isolating. They create a pit in my stomach which tells me to sit on the floor of my shower until it all goes away. They are relentless, heavy, constant and unyielding. And still, they have brought me more community than I ever imagined possible. They are the reason I must say hello to every Sudanese person I meet, they are the reason I have memorised the lyrics to hundreds of Sudanese songs, they are the reason that I want never to lose the language that my mother so carefully instilled in me through prayer verses. In this grief, community tells me that we must carry our grief together, not as a burden, but as a reminder to hold onto what we can, to connect where we can, and to speak out even when silence feels easier, even when our worlds are chaotic, even when floating alone seems easier, even when grief finds us with its feathers. ∎

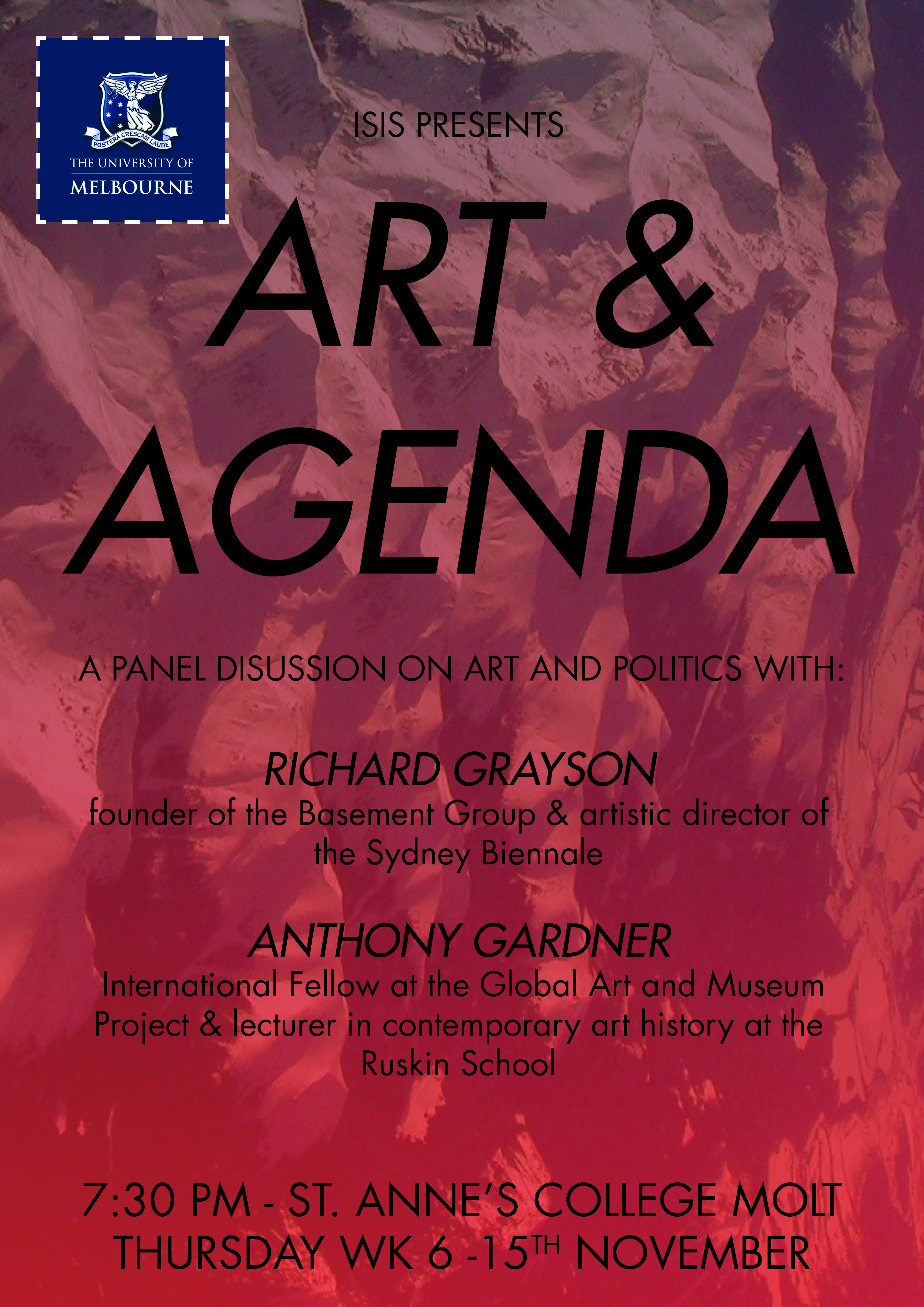

Words by Lina Osman. Image Courtesy of Lina Osman.