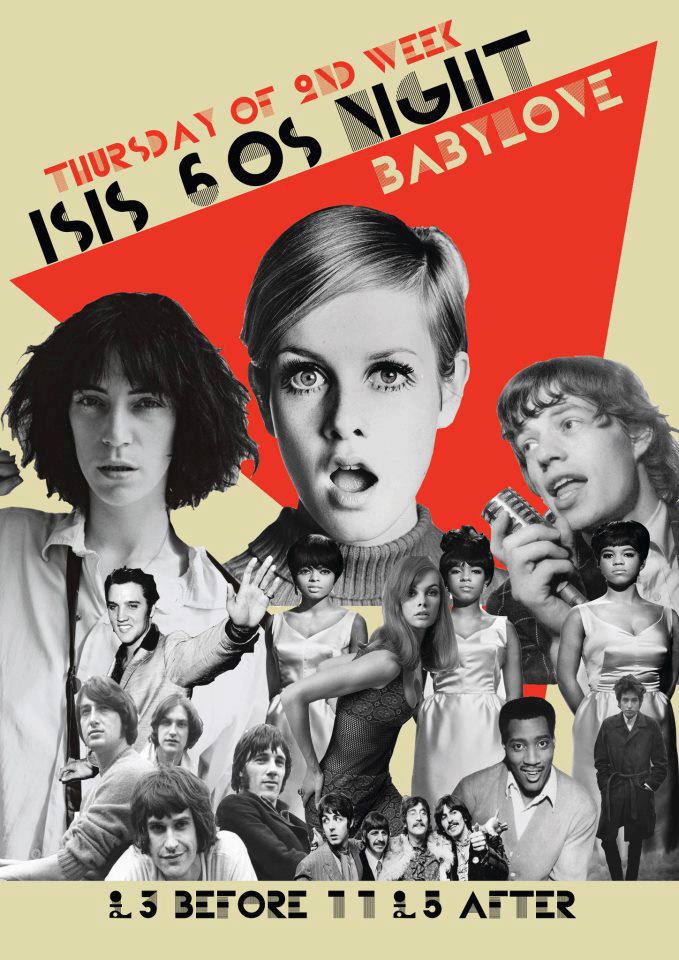

In the country that doesn’t exist

The Foreign Office advises against all travel to Transnistria

“The city does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the bannisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls” – Italo Calvino

Calvino here writes of Zaira, one of his many imaginary cities—one built from its past. A city where the street corners and stairways are etched in memory, where history is soaked up like a sponge. In short: a city frozen in time. One gets much the same impression from a thin strip of land wedged between Moldova and Ukraine, lying on the bank of the mighty Dniester River. They insist upon the title of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, but most in the West refer to them by a different name: Transnistria.

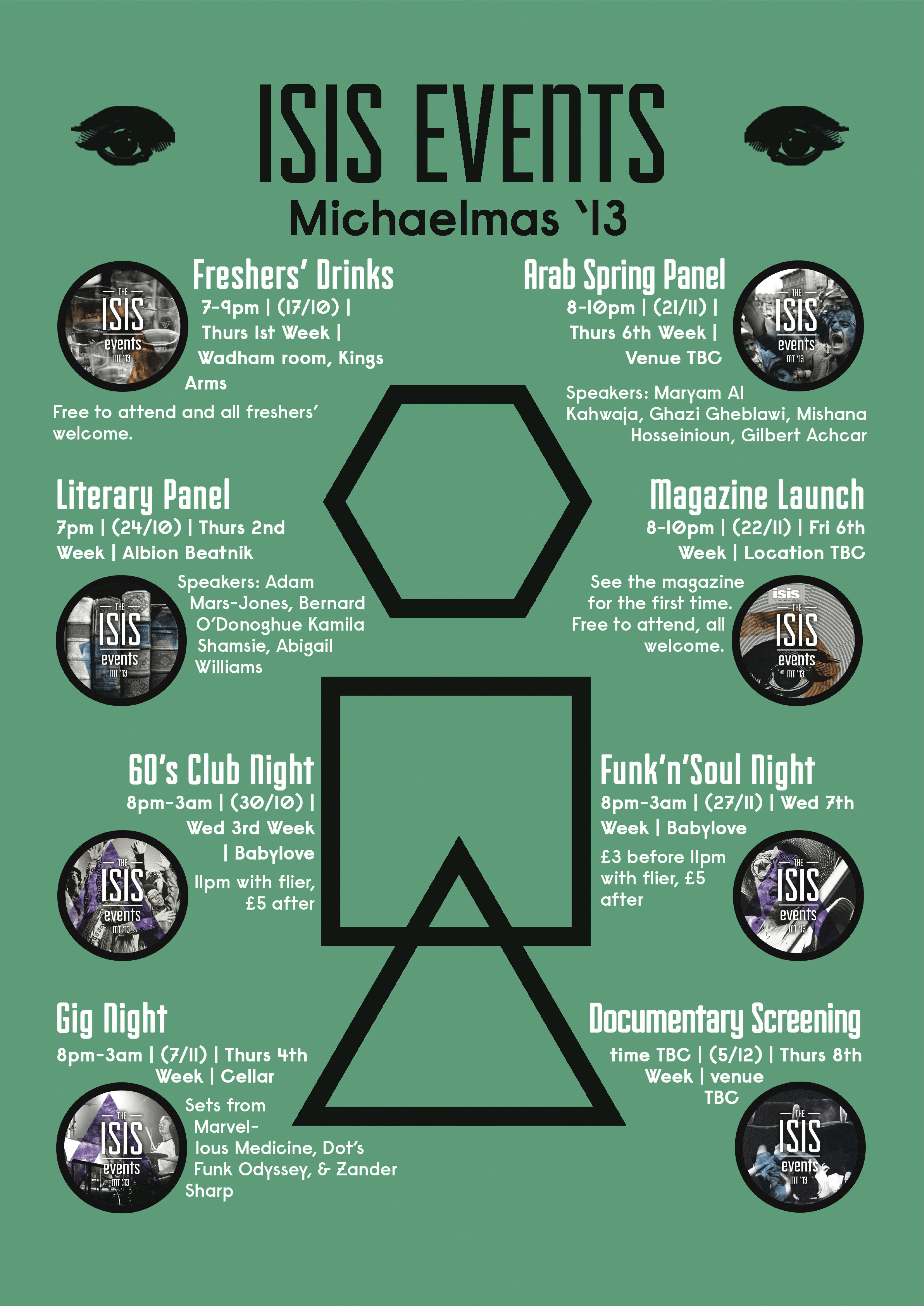

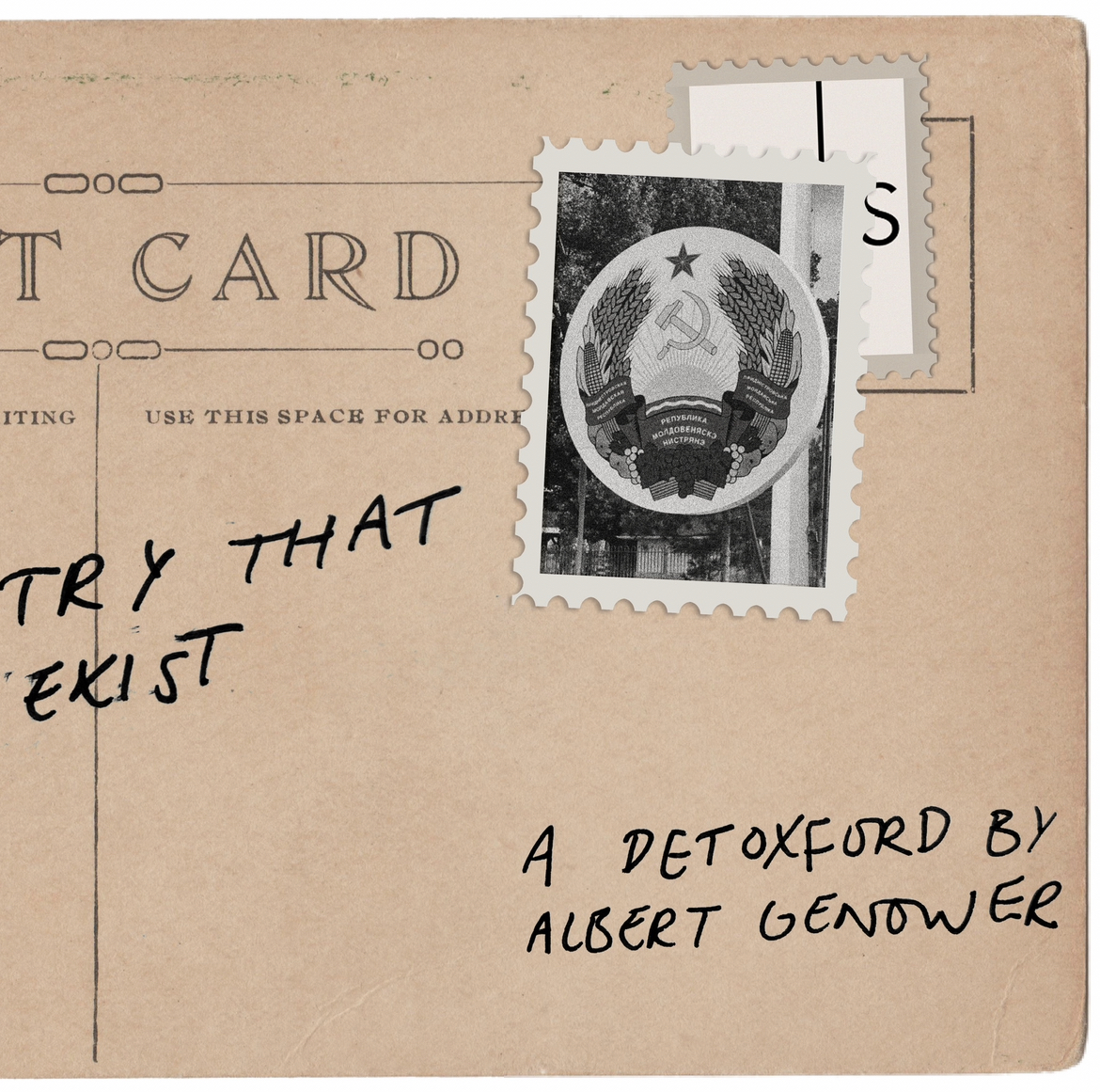

Though it is internationally recognised as a breakaway part of Moldova, Transnistria both functions and feels like a wholly different country—it has its own passport, flag, president, anthem, coat of arms, language, border, army, and currency. Amid the collapse of the Soviet Union, the area east of the Dniester, with its Russian-speaking population, declared independence from the rest of Moldova. Soon after, war broke out, with a Russian-backed ceasefire (but no peace deal) coming in 1992. It still exists as a frozen conflict today, with an unspecified number of Russian peacekeepers prowling the streets, guns and badges in tow.

Coat of arms of the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (Transnistria)

The cheapest way to get there from the UK was to fly to Bucharest, take the sleeper train to Moldova’s capital of Chișinău, and then take a bus to Tiraspol, Transnistria’s capital. The overnight train was particularly fascinating. Named the Prietenia, it was a classic Soviet train with curtains, carpets, and a bar onboard. Wanting to fully commit, we listened to Shostakovich, read Chekhov, and drank neat vodka (actually closer to hot vodka in the stuffy 40°C carriage) as the train chugged through the Romanian countryside towards Moldova.

Aboard the Prietenia

Aboard the Prietenia

After a couple of days exploring Chișinău (an experience strange enough to warrant an article of its own, staying in a hostel full of old men, wine, parrots, cats, a sex shop, and lots of hot, reeking meat), we made our way to the bus station to travel to Tiraspol. The bus (van, really) from Chișinău to Tiraspol technically takes around two hours, though this was somewhat extended by our driver occasionally ringing someone, picking up an unidentified package through the window and delivering it to somebody else. I would love to have known what he was saying, but I am as linguistically pitiful as most English people. At the very least, I had taught myself cyrillic before going, which was a complete lifesaver as Russian is more cognate with English than I had realised.

As with everyone else, we left our bags on our seats as we got off the bus at the border. We had managed to get the last two seats on the bus, and so were last off the bus and therefore last in the queue. Before we had made our way to the front of the queue to get our migration cards, our bus had begun to pull away into the unknown with our bags onboard. I ran after it and managed to clamber aboard, leaving my friend at the border. For a few frightening minutes, I was alone in a bus where I couldn’t speak to anybody, going into a country that doesn’t exist. Without having gotten the migration card, I was entering Transnistria illegally—and it is not the sort of place you want to illegally enter. My attempts to explain or frantically gesticulate to the driver to stop for a minute were unsuccessful, but as the bus continued to pull into Transnistria a guardian angel with a little English knowledge said something to the driver in Russian before turning to me and stating: “You have one moment.” I certainly wasn’t going to take two moments if I could help it, so ran to the back of the bus, grabbed the bags and ran back across the border to have my passport checked, hoping to go unnoticed by the Transnistrian border guards.

Russian and Transnistrian flags flying in Tiraspol

We finally did make it—legally—into Tiraspol. Our hotel sat on the banks of the Dniester. The receptionist explained how Transnistria wanted more tourism, and invested in restaurants and hotels to woo travellers, but Western government advice against visiting the state has hampered their progress. This was evident in the hotel itself: a huge, modern building which opened in just 2022 and that, apart from us, sat completely empty. Owing to its breakaway status, Russian sympathies, and proximity to Ukraine, since February 2022 Transnistria has sat in the Foreign Office’s red zone of travel advice. That puts it a level above North Korea. I felt safe the whole time (if anything, safer than in Bucharest), but it does make sense why it’s there. If something had gone wrong (thankfully nothing did), I would have received no consular support from the British government.

Local children atop a tank from Stalingrad

Transnistira provides a few practical challenges. Being a breakaway state with strong Russian sympathies, neither Western bank cards nor SIM cards work, so it was pretty much paper everything. In one sense, it was romantic to travel in an older style that I wasn’t alive to witness, but on the other I’m used to the conveniences. Until a few years ago, Transnistira did not have its own mint, and so relied on using comically colourful plastic coins, which can still be picked up from the bank as a souvenir. The Pridnestrovian ruble, a currency with no international recognition, bears Russian general Alexander Suvorov, Tiraspol’s founder. Relying on their ridiculous coins and banknotes instead of a card, relying on intuition and memory instead of a map—it was fun but also sometimes annoying.

The first thing you notice in Transnistria is the very thing it is most famous for—its near-total retention of Soviet aesthetics. Transnistria’s flag and coat of arms bear a hammer and sickle, coins bear the same, and their parliament building is foregrounded by a statue of Lenin. Mirroring the advice of Western governments, a brochure in a booth at the border reads: “Your government advises against travel to Transnistria. Transnistria advises against listening for [sic] all your government gibberish!” The note is accompanied by a picture of Lenin giving a friendly wave. “You recognize Transnistria, and Transnistria will recognise you” reads another. At least they have a sense of humour.

Statue of Vladimir Lenin in Suvarov Square, Tiraspol

Despite these aesthetics, Marx would find Transnistria a great disappointment. Lenin, perhaps, a great irony. The insignia of communism and the Soviet Union reflect no commitment to the system that ruled Eastern Europe for a lifetime, nor the ideals that it was founded upon. It is one of the most archly capitalistic areas I have ever seen, under the de-facto rule of a politically dubious corporation that has its fingers in every inch of Transnistrian life. Football, shops, publishing, TV, politics are all, to varying degrees, are controlled by Sheriff. It is widely acknowledged that Viktor Gushan, Sheriff’s founder and a former KGB man, wields the most power in the country, a king hiding in the shadows.

Sheriff supermarkets monopolise trade in Tiraspol. There were actually plenty of Western brands on the shelves—Colgate and Coca Cola amongst the local Transnistrian goods—but it was predominantly local stuff. If you ask me, a couple of Sheriff’s supermarket innovations could be brought to the UK—they have beer on tap for sale! Kvint, the local distillery, produces a great deal of the alcohol available. Wanting a proper vodka bottle as a souvenir, my friend and I each bought one, for 60p and 50p respectively. The 10p clearly makes all the difference, because the 60p vodka was surprisingly drinkable and the 50p vodka hurt my throat, lips, stomach, and soul.

There is a great respect for Vladimir Putin evident in Transnistria. One building flew a flag of Putin’s party United Russia, though I couldn’t tell if this was in any official capacity or was merely the work of an enthusiast. The junk shop we visited sold numerous articles in support of the president, and conspicuously absent from any discussion was the war. In the daytime, the city felt perfectly safe. The streets were clean, nobody bothered us: plenty of people were going about their daily lives. We visited one of those old Soviet amusement parks and rode an extremely rickety ferris wheel that may not have been turned on in years. We ate at Cricova, a little restaurant in the west of the city. The food wasn’t drastically different to what it is in nearby countries, very meat-and-potatoes. By the time we had finished, the sun had set.

Pro-Putin magnets in a junk shop

The city took on an edgier atmosphere at night. Along the main boulevard, old Ladas were drag racing and doing donuts. Several bleak looking windowless casinos could be found along the roadside, peppering it with men who made Transnistria’s reputation for smuggling and organised crime believable. More humorously was a shop called IKEA, with a bright neon IKEA sign and IKEA logos plastered all over it. Needless to say, it was not IKEA. I don’t know what they sold. After walking down some completely unlit streets to our hotel, we made it back for the night, sitting on the balcony and watching the Dniester. My visa was only granted for 24 hours (despite my friend getting his for 48), so our time in the morning was very limited. We visited a junk shop, the bank, and a supermarket before getting the bus back into the 21st century in Moldova. ∎

A late-night florist in Tiraspol

Words by Albert Genower. Images Courtesy of Albert Genower.