Futile Reflections

“If I write what I feel, it’s to reduce the fever of feeling. What I confess is unimportant, because everything is unimportant.”

Ideas are futile unless articulated.

Ideas are like water, with a transparent nothingness that only solidifies after finding form in the contours of words. But if ideas, once grounded by words, gain significance, where can that mysterious significance come from—other than ideas themselves?

Fernando Pessoa came to my mind as I thought about this. Reminiscent of the dreamlike quality pervading his book The Book of Disquiet, where narrative voice is hazy and structure fluid, my thoughts are also evasive, and I wonder whether they existed at all when nobody else is aware of them. So, thoughts are nothing, no-thing. Correction: thoughts are not things, but still seem to have something in them. When others recognize these thoughts, or merely know of them, I find instant relief—as though the final word had been said. My long suspending case is closed, the existence of my ideas confirmed—I can recline for a moment, finally.

Ideas: unlike speeches, audibly registered and consuming time to deliver, and writings, visually registered and consuming space, ideas take up no such perceptible dimensions. In all fairness, ideas don’t exist, etymologically speaking. Exist derives from ex–sistere in Latin, where sistere signifies the verb stand; similarly, être (to be) in French derives from the Latin stare, literally meaning “to stand.” Our language is biased towards the tangible—things that physically stand are conceived of as existing. As language both reflects and sways our view of the world, while the link between the material and existence strengthens, that of the immaterial and existence weakens. See? ‘Immaterial’ not only denotes the quality of being non-material, but also insignificance.

“A work that is finished is at least finished. It may be poor, but it exists.”

Following this, written works most certainly exist, in contrast to ideas. A greater number of written works reflect greater richness in ideas, and incomplete drafts reflect incomplete ideas. Writers, after all, can’t be paid per idea, so they’d best keep producing written works. Even if a writing doesn’t perfectly reflect the idea, it still seems much preferable to ideas that rot in the back of the mind. Ironically, this very draft that I’m writing is quite likely to end up in Google Drive, undone, like many times before. It did happen—I did not dream of it—unable to turn the idea into a pitch before chance of rejection. More ironically, pinning words down into this essay is itself driven by my fear that these ideas are virtually futile. There goes the cycle.

Now, does it really stand that drafts and ideas in the composition phase are much lesser than finished pieces? As the masterpiece that brought Pessoa universal renown, The Book of Disquiet was by nature incomplete; a revision was conceivable for the manuscript when it was discovered from the author’s trunk 47 years after his death. The book formally assails our notion of ‘completeness,’ consisting of fragmented vignettes, like diary entries, that sometimes break off mid-sentence. The Book of Disquiet was only completed upon the death of Pessoa, rendering its completion impossible by the author himself.

“I’m astounded whenever I finish something. Astounded and distressed. My perfectionist instinct should inhibit me from finishing.”

Pessoa’s writing remained incomplete the entire time—recognition of others was the sole difference—I unwittingly return to the beginning of the debate: do thoughts and writings only gain value amidst attention from others.

Simple gestures like finding manuscripts in a trunk and publishing them wouldn’t change much; what was there has always been; nothing was born, nothing perished. Pessoa’s writing had substance, though not material substance, even when no one else had read it just yet, even when he was mentally moulding the first drafts. There was inherent beauty in his attentiveness to the paradoxical facets of living and in his sensibility to the voices of many whom he is not. We would only know of his attentiveness and sensibility via his writing, and his language was only a filter that manifested these qualities. So that’s a no, shortly. Albeit intangible and formless, ideas too come into existence in their own way, and it would be misguided to dismiss drafts when they fail the expectation of becoming a finished piece or making it to publication. As art imitates life, so writing imitates ideas: in both cases, never quite the other way around.

I went to Southern France this vacation; I went to Arles, particularly, for Van Gogh. My neighbours told me that Arles pales in comparison to Amsterdam because it exhibits so few authentic Van Goghs. Correction: I went to Arles particularly for the time Van Gogh spent there, for the flame-like cypresses and poppies next to which he painted and dreamt—I wasn’t even aware that his paintings were there until my neighbours enlightened me. But I still adored Arles, because it first awakened the painter’s keen love of nature and his acute awareness of the world around him. Everything else, finished paintings, sold pieces, exhibitions seem subsidiary to what Van Gogh felt in those primary and transitory moments of creating his art.

Late March felt like an early prelude to summer when I arrived in Nice, the sunlight and breezes flowing languidly across my skin, and the sea endlessly rushing up the pebbles. As if by instinct, I began searching for words to encapsulate my strange longing for vitality, but language was elusive and words escaped me—I worried that I might not be able to recall how I felt at that precise moment. Pondering over these things wearied me, and I decided to let my thoughts rise and ebb without the pressure of immortalizing them. I am content to have had them right now, even if only for now. The experience alone was ravishing; there was no need for additional words to aid its becoming something, for it already stands by itself, despite its incorporeality. Anything extra would tip the perfect balance and break the spell: I took delight in its secrecy.

“Right now, I have so many fundamental thoughts, so many truly metaphysical things to say that I suddenly felt tired, and I’ve decided to write no more, think no more. I’ll let the fever of saying put me to sleep instead, and with closed eyes I’ll stroke, as if petting a cat, all that I might have said.”

‘Futile’ derives from the Latin adjective futilis (leaky, futile), and verb fudere (to pour); just now, I realize how immaculately it captures the nature of my ideas. Perhaps it is also time to let my ideas flow and pour out, complying with their fluidity and amorphousness, just like seawater in Nice escaping through my fingers. Words, surely, are powerful. But some days one must turn away from pen and paper and simply not wri

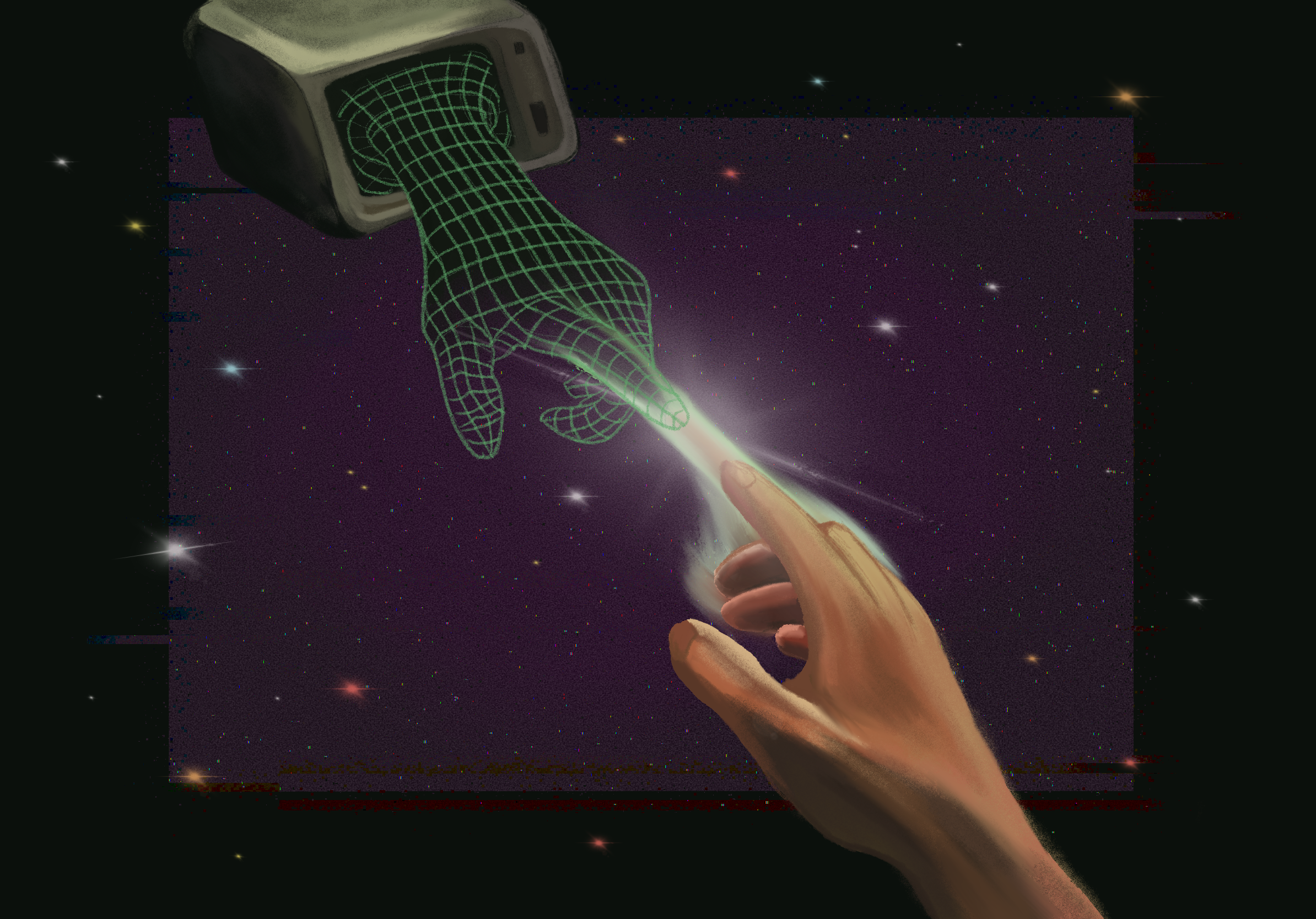

Words by Ziyue Zhang. Art by Liberty Mountain.

For Fernando Pessoa.