Orlando: from the West End to Magdalen gardens

I didn’t like the West End adaptation of Orlando when I saw it in January 2023. I was convinced the concept was all wrong, and Neil Bartlett, the play’s adaptor, was the guilty man behind the crime. I spent the entire journey home on the Central Line ranting to my mum about how goddamn diluting it all felt, how distanced it was from the novel I had read and loved. I’m sure the people on the carriage thought I was insufferable. (I was.) I had to confess, though, that the star–none other than Emma Corrin–was brilliant.

The next day, I went in to work and overheard a very cultured colleague talking about how much they adored the adaptation. I found myself blurting out my discontent for the play, my meagre two-star review, and received raised eyebrows from the rest of my colleagues. I cowered in my seat. My theatre critic debut had failed.

Why the two-star review? Was I being pedantic, playing devil’s advocate? Probably.

My case was as follows: rather than telling the tale of the novel itself (published in 1928), the West End production starred the character Orlando, surrounded by a sea of shiny Virginia Woolfs. I took issue with the surplus of Virginias on stage. Each individual Virginia would help ‘write the story’ of Orlando in their notebooks as it was unfolding in real time in the theatre, guiding Orlando through the ups and downs of life. Rather than being new and exciting, it felt like someone was trying to make Orlando accessible and diluting it in the process. Snobbish, I know. But I strongly believed it was taking away from Woolf’s work: she would be rolling in her grave at the idea of her authorship being the primary focus of the novel. Oh, also, there was a really clunky line about Woolf’s suicide.

A year later, I like to think I’ve grown as a theatre critic. And so, when my friend texted me “MUST BUY TIX TO ORLANDO,” I was shamelessly excited. Maybe the ‘Orlando X Oxford’ collaboration would cure my traumatic experience of Not Liking A Play. I certainly wasn’t expecting a cast of 20-ish year olds to perform the same script I’d heard, and disliked so much, a year ago. You’ll be pleased to find out it was the perfect remedy.

Surprise: I found myself enjoying it. I was completely aback at the talent of star Wally McCabe, who plays Orlando, at the strikingly fluent Russian that left a cast member’s mouth, at the cats which roamed onto the stage with great ease (the stars of the show, really–they must’ve been paid actors). Behind the scenes were mastermind directors Phoenix Barnett and Raphael da Silva; producer Eve Wilsmore; assistant director Jupiter Green and assistant producer Charlotte Oswell.

In one bizarre moment, Neil Bartlett, playwright, was brought up on stage to ask for Orlando’s hand in marriage. As co-director Phoenix Barnett put it, “he was so flamboyant with it and everyone gave him a massive round of applause afterwards.” In Phoenix’s words: it “was just super, super special.” Reciting his own script felt like a deeper moment for him, who joked that “if we want to deep this and go all English student-y… the play Orlando has Virginia Woolf, the author, in it, so then we added the layer on top and put Neil Bartlett in his own play which [is just] so meta.”

Features writer Lilia Khan went to interview Wally McCabe after their final night. Wally told Lilia, that as a “non-binary person […] I love this novel to death, and I really relate to it from that gendered perspective.” Speaking about their intimate connection to the role, Wally revealed “it’s somewhere in between… playing Orlando as a character versus sort of dissolving into Orlando as an actor and as a person.”

(Orlando, Wally, stays on stage during the interval.)

It was Wally’s decision to stand on stage for the entirety of the interval, stone-still: “I’m there, and I’m acting, but I’m also absolutely having thoughts in that moment.” Why? They wanted it to be like the rest of the novel– a kind of “stream of consciousness.” Wally surprised Lilia by comparing Orlando to Twilight: both, they said, are “shamelessly honest, almost embarrassingly honest, in that they’re just very raw thoughts and very raw feelings that aren’t always… the most beautifully put.” They went on to closely note, “Orlando is filled with this yearning and it’s yearning all the time, it’s yearning to be someone else, it’s yearning to be with someone else, it’s yearning to be at a different time.” At the end, “Orlando comes to this realisation of ‘what is my favourite time,’ well, it’s right now.”

Orlando ends up madly in love with Sasha–played by Anna McMullan. The two have fiery sex on stage (don’t worry, it’s all theatrical, and they’re hidden by a row of Virginia Woolfs), leaving Wally shirtless on a bed for the audience to ogle. Lilia asked Anna what it was like playing such a sexually charged role–after all, Sasha is a Very Sexy Russian Lady–and Anna laughed, but noted, “we had an intimacy coordinator who helped us through that.” Ultimately, Sasha leaves Orlando behind, a broken promise of love, and Anna knew this was integral to her character: “I knew that I had to play very distantly, so it’s both emotionally disengaging in the way that I speak, but also in my physicality.”

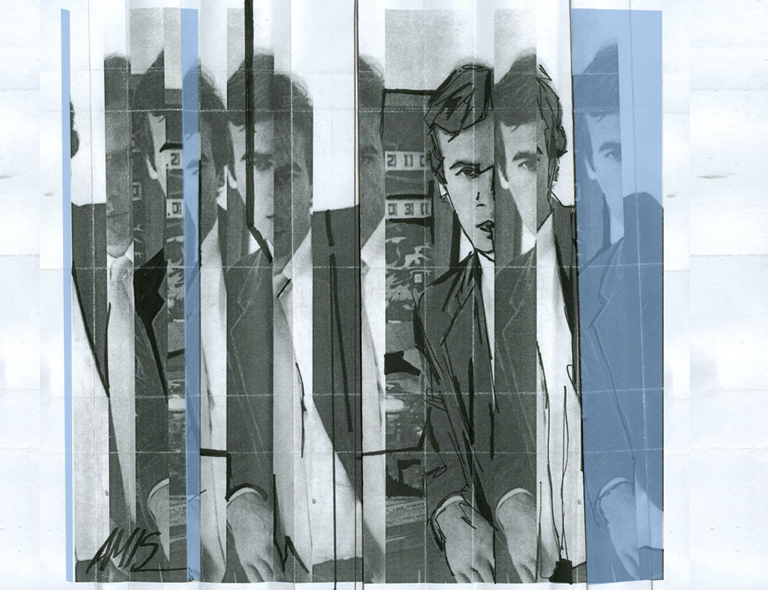

(Left to right: Orlando, Wally, and lover Sasha, Anna McMullan.)

Lilia spoke to another lover of Orlando’s–George Loynes, who plays Harriet/ Harry– “I play a man pretending to be a woman because he can’t be out as a gay man.” How did he feel wearing a dress on stage? George was “feeling a bit nervous about going on […] in a dress”. George has blushed cheeks and thousands of clips in his hair: I can assure you, he looks fabulous on stage. “The last thing I’d done was just a bit more serious [..], so it was quite fun to just have fun, put on a dress, do some drag, do some silly stuff. But obviously really nerve wracking as well.”

Lilia went to interview the costume director behind these gorgeous dresses–Biba Cope-Brown, assisted by Mikela Persson Caraccilo and Connie Higgins. Biba mentioned the continuity of the use of blues in Orlando’s costumes: “When that came together, it was really nice to see that bit of continuity in the character. Because obviously there’s so much change happening, it’s nice to have something a bit stable.” Of course, the play covers 300 years, and only runs for two hours, so Biba and the team had a hard job having to cover all the periods. Biba agrees: “We were so focused on getting the right periods. Because it was mainly the silhouette that I was concerned with.” From the Jacobean outfit (“big puffball shorts and that little waist”) to the Regency dress (“the huge hips”), the costume changes are quick and seamless (no pun intended). Orlando, on the other hand, doesn’t wear many clothes. Biba was relieved to know that Wally was “very comfortable being topless or showing a lot of skin… Because obviously there’s a lot of taking corsets on/ off, shirts on/ off, being in their pants essentially for most of the show.”

The Virginias are all dressed slightly differently, though, in keeping with Neil Bartlett’s focus on diversity and variety in the cast. In his West End production, all Virginias were meant to come from different races, age groups, classes, backgrounds, etc. And so, on the stage at Magdalen, each Virginia got to choose what they wore, and had different notebooks to show for it. The costume designers told the cast to go for “good old 1940s style,” letting the actors pick and choose what they wanted. Scarlett [Fountain-Wilkinson], who played Nell and is also one of the Virginias, as Biba pointed out, “keeps all of her jewellery on.” Biba laughed and remarked that “quite a lot of Phoenix’s trousers ended up in the mix.”

On the night that I went, there was a private Q&A with the playwright Neil Bartlett. (Yes, the one I had previously declared a theatrical criminal, but I’m a changed woman.) Although I still thought some of the lines fell a bit flat–a chorus shouting “use your words, Orlando!” does admittedly feel a bit infantile for Virginia Woolf’s mature writing–I found the script surprisingly brilliant. Born out of it was a lively, ambitious, and dynamic production. As playwright Neil Bartlett would later say, there was something oddly moving about seeing a cast all the same age. I’d never thought about that–it’s a given for student drama–but he had a point. It was odd, but moving, to watch someone ‘grow up’ around a cast that was yet to.

We moved to the President’s lodgings for the Q&A (gorgeous, in case you’re wondering). A crackling fire was lit. Neil sat up front, Magdalen-branded mug in hand, ready to be questioned by the directors and producers of the play. I sunk into the sofa. Firstly, Neil thanked his husband for being there– the two shared a long, intimate look. (I noted that they had the same glasses. I love when couples blend into each other.)

And then he got stuck in. He told us of his years at Magdalen as a gay man in the 70s: the gay gentlemen’s clubs in town; his hard work alongside feminist activists; punk shirts and flamboyant outfits. Neil didn’t come out as gay until his second year at university. It was a hard time and place to be out: he told us of the time a gay student got asked to leave Oxford when porters found him and another boy sitting in his room. Neil was lucky enough not to have an experience like this, but he continues to carry his queer identity into every work he produces as a badge of honour.

Working in the West End wasn’t always easy: Neil had to put his foot down a few times. He said one of his non-negotiable requests was having a diverse cast, from entirely different backgrounds. Neil proudly told us of the mix–from a Nigerian Virginia to a Virginia in her 80s– he wanted to make sure this diversity existed due to his experience of the West End as an exclusive environment. Neil also insisted that there be a mostly female and non-binary cast, as the opportunity for women to perform in the West End is so rare. He tells us, proudly, that he hopes one day it will be played by an all-female and non-binary cast.

As for casting Emma Corrin as the star? Apparently, Emma just fell into their laps. Neil went to an emergency meeting one day where he was told that they were willing to play Orlando. He was shocked. They brought immense popularity to the show, and Neil was excited to have them. Interestingly, he wrote the script with another actor in mind, but found himself not having to make many changes for them.

Moving away from the politics of the West End, Neil got stuck into the core of the play. He described it as “breathless,” a constant movement between the actors on stage. Neil wrote the play at a very specific time in his life; much like Woolf wrote the novel at a specific time in hers. Woolf was yearning after her lesbian lover, Vita Sackville-West. Neil had the idea brewing in his head for a long time until he put it to practise and got highlighting. He wanted to avoid inserting his voice as much as possible, bringing in lines from other plays of the period. For example–Elizabeth I (played by Hugh Linklater)–is mostly taken from Hamlet, then the script turns into John Webster, and slowly but surely draws at more contemporary references as it becomes newer and newer. As Phoenix mentioned, “Orlando is kind of a smorgasbord of everything and everyone.”

(Left to right: Mrs Grimsditch, Rijul Jain; Orlando, Wally McCabe; Chorus, Gillies Macdonald)

When Lilia and Albert Genower went to interview the co-director, Phoenix, and the producer, Eve Wilsmore in more detail, they spoke about how gender was shown differently: “The way Wally played Orlando and the way Emma Corrin played Orlando will give you different perspectives of gender and of Orlando’s gender because they’re different people playing them.” One of the lines, “ladies and gentlemen and everyone” becomes a bit of a joke– as Eve put it, “I think honestly when I first read that I didn’t know how to take it.” But the line soon becomes “very tongue-in-cheek” and ceases to land as a joke: “once the play progresses, [the line becomes] more of a comment on the fact that you just have to make it ‘everybody’ because there is no one experience of gender in play.”

Speaking of jokes, the play is meant to be funny. As Phoenix put it, “I’m a big believer as well that if you can make people laugh, you can make them listen.” He goes on to note that there’s a contrast between “some of the funniest moments (obviously Hugh having an orgasm is completely ridiculous)” and “the deepest parts” of the play. And the garden setting allowed for the breaking down of the fourth wall. As Phoenix noted, “there’s no barrier between the stage and the audience […] it’s kind of involving and enveloping everyone. I think that Wally staying on stage feeds into that a bit, in the sense that the actors are just there, you can go up, you can touch them, but they’re also someone else.” Eve agreed with him: “I think it’s just the immersion. Even having the little arches on the side which you could see through to backstage, nothing is really covered in the garden. We did consider putting up sheets at the side of the stage […] but honestly having that exposure, like Phoenix was saying, is what we wanted.”

I first read Virginia Woolf’s Orlando when I was seventeen. My copy was taken from my parents– coffee stains included– and the spine snapped in half when I was reading it. I felt accomplished, like I’d read it intensely enough for the physical copy to snap.

Hearing from others who loved it as much as I did, perhaps even more, feels like the remedy I wanted a year ago. As Eve said, the cast really did enjoy the production. She told Lilia: “Watching it finish every night and having that feeling of ‘we get to do this again tomorrow’, ‘I get to see these people again’, ‘I get to watch this again with Phoenix and Raph by the back’ and just experience it and […] think ‘we did this, and we all did this,’” was “the best part for me.”

And so, watching a student-run production of Neil Bartlett’s script changed my mind. Funny how a concept can hit home in Magdalen gardens, but not in the West End.

I’d like to move my two-stars up to five, please.∎

Words by Bella Gerber-Johnstone. With additional thanks to the extensive interviews hosted by Lilia Khan and Albert Genower. Images courtesy of Kian Burgess.