Equus: Talking to director Marianne Nossair

Bestiality. Making out with horses. Sweaty, sexual intercourse fantasies atop their backs. Dreams, nightmares, and the sacred deification of them. Not exactly what I was expecting from my Saturday afternoon; but instead of being horrified or repulsed, I came out of Equus strangely sympathetic towards the tortured protagonist, Alan Strang, and his desires.

Equus is a 1973 play by Peter Shaffer. Shaffer was inspired to write the play when he heard of a crime involving a 17-year old boy in Northern England who blinded six horses. What followed is a two-hour long exploration of the psychology behind such an act as Shafer constructs it. The narrative of the play follows psychiatrist Dr Martin Dysart, who uncovers the experiences of the boy in question, Alan Strang, while simultaneously coming to terms with his own sense of purpose in his profession. Alan is brought to Dr Dysart’s clinic, and we follow him as he discovers that Alan has constructed his own personal theology of horses, with the godhead “Equus” whom he regards with a mixture of sexual attraction and religious fervour.

Needless to say, the play is weird. But it’s wonderfully unique. When I asked first-time director Marianne Nossair what motivated her to pick this specific play, she tells me that she “wrote about it for A-level Drama,” where she had to map out “what to do with the lighting, the staging, the production, everything” and she felt it would “really just be a waste” not to take those efforts of theoretical ideation and put them into practise. I watched the matinee show on the Saturday at the Michael Pilch Theatre, and was blown away by the cast’s exquisite, emotionally powerful and sensitive treatment of each of their characters; Joe Rachman’s nervous, erratic anger, Ethan Bareham’s professional, self-important Dysart deserve standout mentions, but Vita Hamilton’s sardonic portrayal of the magistrate, and Nate Wintraub’s aghast stable-owner were beautifully performed.

The physicality of the play was a special part of the direction, Marianne tells me; Ollie Perry Wade (who plays the central horse, Nugget), just “found his inner horse one day, when something clicked in him” and from then onwards was brilliantly precise in his portrayal of the animal, deftly avoiding any over-exaggerated physical comedy. In a crucial scene at the end of Act I, Alan climbs atop and rides Nugget, and the viewer is almost transported; you forget that you’re in a theatre, watching one student climb atop the back of another student; no, it’s Alan Strang’s religious fervour and intense connection as he rides the object of desires and of his prayers, a horse that is before you.

The play canvasses a variety of themes, and does them all justice. Alan’s worship of horses is intertwined in his family’s dynamic with religion: his parents constantly argue about the proper role of worship – his atheist, socialist, hardline father seeing it as “silly nonsense” and his devout, sincere mother sneaking it into Alan’s life nonetheless. In an impassioned monologue, his mother avows any blame: “Whatever’s happened has happened because of Alan. Alan is himself. Every soul is itself. If you added up everything we ever did to him, from his first day on earth to this, you wouldn’t find why he did this terrible thing – because that’s him; not just all of our things added up.” Whether you believe her or not, one can’t help but find some truth in the idea: perhaps everything wrong with you can’t be explained by childhood trauma and your parents, actually.

In another impassioned, deliciously meandering monologue – the opening one infact, Dr. Dysart says: “And of all nonsensical things – I keep thinking about the horse! Not the boy: the horse, and what it may be trying to do. I keep seeing that huge head kissing him with his chained mouth. Nudging through the metal some desire absolutely irrelevant to filling its belly or propagating his own kind. What desire could that be? Not to stay a horse any longer?”

Like Dysart, I find myself wondering about the horse; or the general horses. In July 2005, 45-year-old Kenneth Pinyan was found dead. The previous night, he and a group of men, who met regularly, went to get drunk and have sex with horses. The horse they regularly had sex with was apparently not in the mood, and so they wandered onto a neighbouring farm to be anally penetrated by – and I’m not making this up – a horse nicknamed Big Dick. Doctors ruled Pinyan’s cause of death as acute peritonitis. (The erect penis of a male horse is about two and a half feet long.) A disturbing video of this feat exists online and was circulated at the time.

Most interestingly, this act was not illegal at the time by Washington law, because it had accidentally been decriminalized with sodomy. Obviously, there was a trend of criminalizing this following the disturbing, and public case; but when criminalizing this, lawmakers had to be careful not to centre the crime around nonconsensual sexual acts performed upon animals, as this would outlaw a large proportion of breeding, milk production and husbandry industries, which routinely inseminate, genitally manipulate and sexually arouse animals. One of the most convincing cases for veganism (I’m not a vegan, this isn’t an agenda, I promise) I’ve seen was the 2015 manual in Farmer’s Weekly, which instructs readers to ‘properly restrain’ the cow, using what the industry calls a ‘rape rack’, before loading a ‘semen gun’. It also includes instructions to ‘prepare the cow’s vulva with a paper towel’.

Today, many zoophiles accept and celebrate the label, insisting that it is a sexual orientation, like homosexuality or bisexuality. Mark Matthews, one of the leaders of the movement, published a memoir in 1994 about his romantic and sexual encounters with horses titled The Horseman: Obssessions of a Zoophile. In it, he describes his first sexual interaction with his pony, Cherry: ‘They made slow love, using their whole bodies in foreplay, rubbing against each other, caressing with hands, lips, noses, teeth, using all that each had to use; then, when his testicles and penis ached with arousal, he entered her and they rocked on their feet in blissful harmony … ‘I love you, little girl. I’m in love with you. You’re so sweet, so funny, so – oh, Cherry, my darling!’ He hugged her neck, hung her head over his shoulder, rubbing his cheek against her sleek coat.’

When Cherry died, Matthew was grief stricken; and he found love in the arms (hooves?) of another mare eventually: ‘I feel a warmth and companionship that I can trust. No games, no power plays, just honest affection.’ Some of this strange tenderness, and unexpected authenticity of emotion is found in this production of Equus; at no point can the viewer doubt that Strang does feel a sexual fascination, a desire, a reverence, and an affection for horses. While the play itself does not go into any more graphic detail than fondling and some physical affection expressed towards and from the horse and Alan, it is more than enough to elicit disgust, shock and horror from the viewers. Marianne says this reaction is what she finds intriguing in plays; the weird, repulsive or unsettling calls to her as a genre.

The play I watched managed also to elicit a begrudging sympathy for the situation, as echoed by Dr. Dysart. In conversation with the magistrate, who asks him to help Alan, to return him to ‘normal’ he protests, displaying a surprising envy for Alan, and all his wards’ situations; he resents the boring ‘normalcy’ of his lives, insisting that to dictate to them what is normal is to take away what is special, powerful, meaningful about their existences; at least Alan has purpose, at least he understands what he is meant to do with his life. Notably, the playwright Shaffer has alluded to the fact that the play might be a metaphor for Shaffer’s own homosexuality; Alan’s treatment at the hands of his father, the internal struggles and suppression, the focus on his non-traditional masculinity all point this way. Regardless of whether it is understood this way or not, Marriane Nossair’s portrayal of the story of this young man’s struggles is poignant and powerful.

In our interview, she discusses some of the more mundane struggles faced in the production process. Marianne says that the “organisational responsibilities” were new for her, and different from her previous Assistant Directing and acting experience. Getting the rights for the play was slightly complicated; it can range from anywhere between “50 pounds to a 1000 pounds.” For Equus specifically, it was a bit “more expensive than normal plays,” and there was a clause that “mandated full-frontal nudity, and you couldn’t get the rights otherwise – you could be fined and sued for not doing it.” Understandably, Marianne didn’t want to ask a student to go to such lengths, and citing welfare reasons, was able to work it out. Most of the auditions were “in-person” so that she could see if “they take direction.”

The licence “stipulated that Alan and Dysart had to be played by male-presenting actors,” restricting the amount of female roles in the cast. They had their first meeting with the crew, in week 0 of Hilary and put in their bid. Casting took place in Week 7, with finalisation of the cast over Week 8. This was followed up by constant rehearsals in Trinity Week 1 onwards.

Notably, Ethan – who plays Dysart – did the play during his English finals! The show was blocked and run through by week 3 to accommodate for the same with four to five rehearsals a week. The play also had an intimacy coordinator on set for the scene’s between Alan and the farmhand, Jill, which Marianne said was incredibly interesting and helpful in “professionalising the setting,” making it “extremely choreographed” as “any other scene would be.” Marianne tells me she chose the Pilch as she wanted to differentiate between the front of the stage being “memories” or “visions,” while the back would be “the office, and the real world,” and wanted to use the four entrances for the horses in the aisles, a feature unique to the Pilch. Notably, the setpieces of the horses’ masks were difficult to construct and collaborative – the cast stitched the leather on themselves and each mask was specially fitted for each cast member. They were only obtained properly on Wednesday (opening night), and despite not rehearsing with them, they were incorporated incredibly naturally into the performance.

Currently, the horse masks are sitting somewhere in Mansfield JCR – other than Nugget’s, which Ollie has taken home as a memoir of his time as a horse. ∎

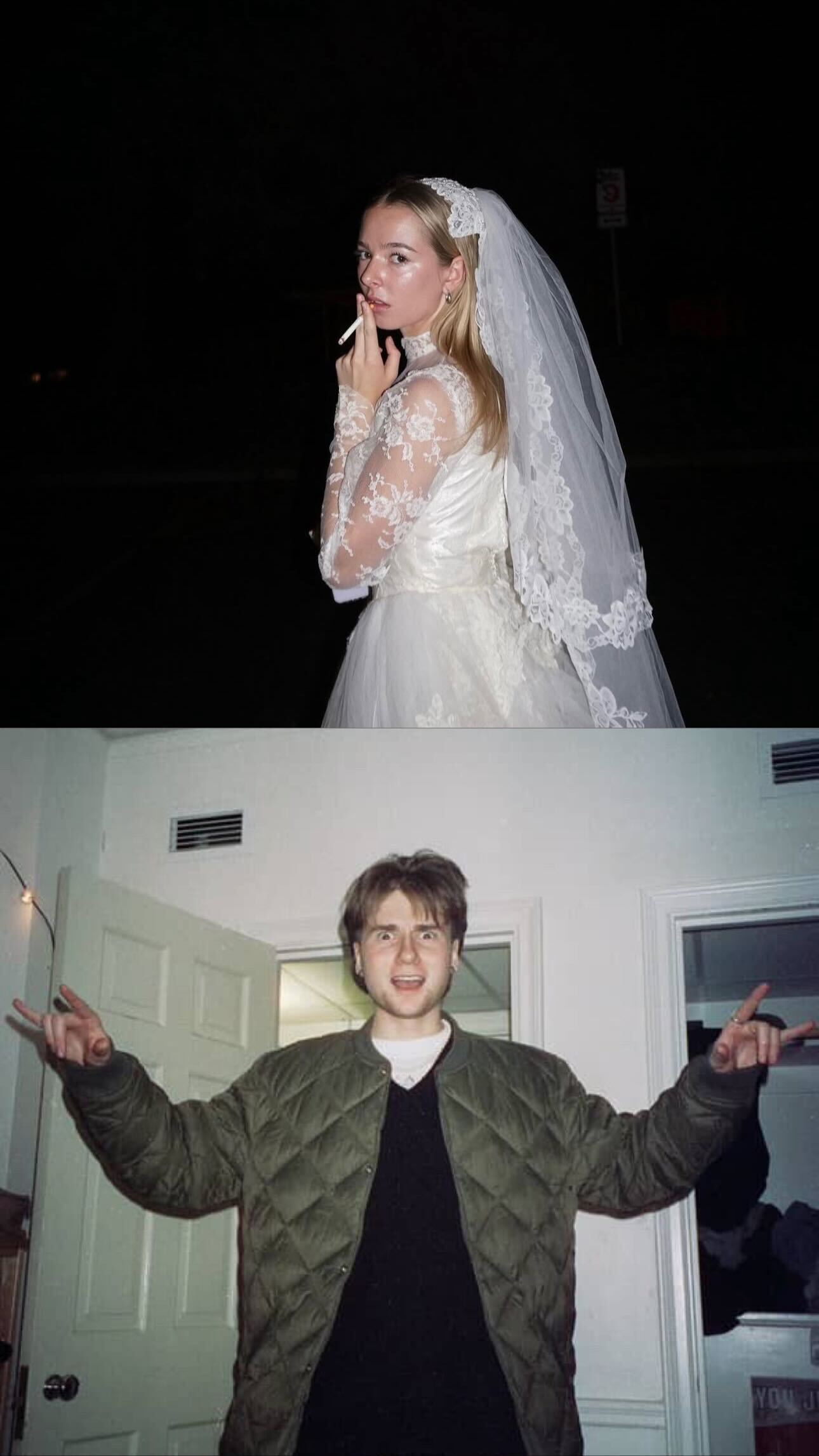

Words by Treya Agarwal. Image courtesy of Equus Facebook.