From Bin to Body: The Role of Rework in Alternative Subculture

Our consumer climate creates a body-to-bin culture, making people believe that an endless stream of new clothing is needed to stay on trend. DIY subculture communities subvert this mainstream model by recycling apparent rubbish into unique items for long-term wear. This bin-to-body fashion cannot be unpicked from the collective mentalities underpinning it. The practice of making DIY clothing brings people who share anti-consumerist values together, forming a common thread in their alternative communities.

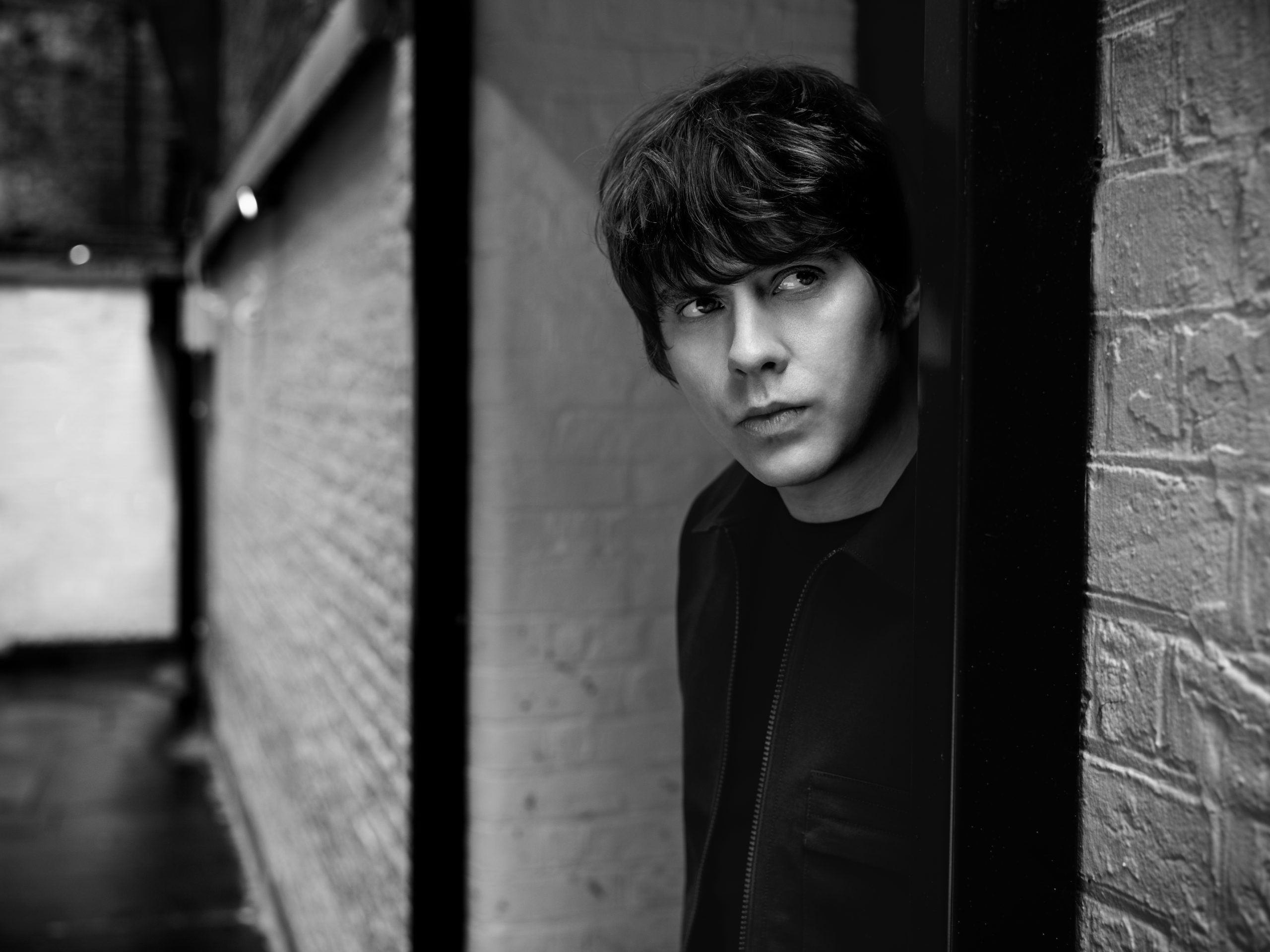

One of the original UK subcultures was 1970s punk, born from the UK’s volatile political climate and changing music scene—think The Slits, Crass and the notorious Sex Pistols. DIY ‘battle jackets’ are a punk staple: worn to gigs adorned with spikes, studs and hand-painted, whip-stitched patches attached with dental floss. Early 1980s crust punks smeared beeswax or even jam into patch pants to stiffen denim. Remnants of early punk can still be found today: Ink (pictured below) is part of Brighton’s DIY punk, goth, and psychobilly music scenes: a fusion of rockabilly and 1970s punk rock. Their The Cramps leather jacket is thrifted and painted, with 315 large cone studs added by hand. This shape of stud has been used as a symbol of non-conformity on British punk jackets since the early 1980s. Later, goths intertwined the outrageousness of punk with a Victorian romanticism, wearing winklepickers (dark pointed shoes), adopting other mourning couture from dusty shop corners and subverting cross iconography into an overt statement of demarcation. Post-punk ‘baby bats’ flew to gloomier bands—. Venus (also below), one of today’s ‘trad’ goths, made her harness out of six pieces of chain that she cut with a hacksaw, using pliers to attach them with a padlock at her front and carabiner at the back. Those belonging to traditional subcultures continue to resuscitate unusual materials, continuing that subversive cycle from bin-to-body.

These iconic early subcultures divided and expanded into a kaleidoscope of communities, from metalcore to emotional hardcore ‘emos’, to the mass of obscure styles and DIY-focused communities that exist today. While DIY isn’t necessary to be part of an alternative subculture, making your own clothes is often a symptom of a subculture’s ideology: if you’re anti-capitalist you’re not going to be mass ordering from Shein when equally cheap, ethical solutions exist. DIY directly undermines the view that to solve your problems, you must buy a solution. Its materials, sourced anywhere from scrap fabric bins to family desk-drawers, exemplify not only a ‘do-it-yourself’ but a ‘use-what-you-have’ attitude: to rip, tear, safety pin together and re-assemble ‘rubbish’.

The role of DIY in these subcultures therefore runs deeper than clothing: a ‘do it yourself’ attitude stitches a group of people who listen to similar music together into a shared ethos. Punks create their own zines, book gigs and record music with others in their community. DIY culture is self-made, not prescribed: Abi (below), who added safety pins and badges to her skirt and bandages on her arms, ankles and bunches, was photographed at a grassroots healthcare fundraiser. The community came together to raise money through a day of live transfeminine-fronted music, selling handmade jewellery and clothes. Similarly, Mira (below) plays drums in an NYC punk band and spends her time with “folks of similar inclinations.” Local DIY music scenes are still growing around grassroots venues, where subcultures flourish through solidarity.

With the rise of alternative culture leading to wider accessibility online, new types of alternative fashion communities are growing. Otherwise-isolated members of subcultures now have access to a network. I first met Cove (pictured below, on the left) online during the 2020 lockdown. He handmade his bonnet, and Hero’s headdress as some of the “first things” he DIYed. Both boyfriends have had an “interesting pipeline” in their personal styles: Cove was “trad goth for like three years” before partaking in several Harajuku-fashion substyles. Latex (pictured below) encapsulates the fluidity of subculture today. They can go “completely scene”, attending raves with “big emo hair, big fringe, bright colours”, but they also attend Midwest emo gigs (I’ve witnessed them thrown into a crowd), a music subgenre that spread from 1990s Midwest America to blend math rock and emotional hardcore influences. This internet-aided fluidity of modern subcultures makes room for interests that might have been conflicting in the past: subculture labels no longer have to be stitched so tightly separate.

The growing online awareness of alternative fashion allows established creators, or subculture ‘old heads’ to teach viewers how to experiment with DIY: tutorials and inspiration are a click away. I’ve attempted, and often terminally failed, to follow videos on how to add studs, how to line-sew, paint fabric, rework thrift. There is an increasing cross-section between ultra-specific online “cores” and wider subcultures, where online communities can solidify through shared music and global experimental fashion. Pictured below, Thalia’s Harajuku-fashion EGL (elegant gothic lolita) exemplifies this accessibility to global alternative culture: this Japanese style is also partly “inspired by western antiques, the Rococo era.” Her bonnet is made by a Japanese friend who “sources her own lace” and her socks were scavenged from a second-hand “bin” in Camden Market—London’s countercultural hotspot since the 1970s. Worldwide alternative cultures are now accessible both locally and digitally.

However, the growing commodification of subculture aesthetics represents the antithesis of DIY values. As alternative fashion communities have migrated online, subcultures have been neatly divided into ‘cores’: marketable, fast-moving appearance-focused styles that are consumed and spat out by the digital trend-cycl During the pandemic, these commercialised ‘cores’ were at their peak: cottagecore, kidcore, glitchcore, gremlincore—whatever your heart (or wallet) desires. The label ‘cores’ may have come from the terms ‘hardcore’ or ‘metalcore’—a 1980s fusion of metal and hardcore punk—but here it is trivialised into fleeting trends that die as quickly as they come. By definition, true DIY culture cannot be bought and sold—these trends obscure the home-grown personal styles that subcultures exist to foster, thrift shop prices have soared and online second-hand platforms such as Depop have grown exponentially larger than the pockets of poorer consumers. Fast-fashion websites have even replicated the “handmade” style with a throw-away facade, often ripping off independent designers, and creating clothing that is designed specifically for the body-to-bin cycle.

Despite the commercialisation of subcultures online, real life DIY communities are still thriving, as today’s subculture kids have been motivated to express revolutionary attitudes in new ways. There has been no disintegration of subculture into the commerciality of popular, marketable alternative fashion; rather their subversive communities are becoming increasingly important. Adaptations of traditional reworking techniques are rising as a reaction against consumerist co-options. See Mira’s cropped, hemmed and lino-printed top with the message, you are seeing and being seen, which forces the viewer (her tutor or fellow students at Oxford) to consider how they perceive her. This non-traditional punk expression forces the same self-awareness as its ‘outrageous’ 1970s precedents.

Subculture is alive and breathing—and fuelled by DIY. Photographing just a fraction of the UK’s alternative communities has shown me how their kaleidoscope of self-expression expands in relation to our ever-changing cultural climate. Prisma, pictured below, is the personification of “personal style.” They told me that they are “dressing to my joy” in exclusively colourful clothing, a handmade skirt, pins and ‘kandi’, exchangeable bead bracelets—a staple of early 1990s rave culture that was taken up by 2000s scene kids. Despite their opposite styles, Nez and Prisma both live within alternative and, importantly, queer communities, which have been able to assimilate as modern subcultures have diversified: “My life is the queer scene; there is no scene outside of it to me.” Their outward presentations are intrinsically pinned to their identities and cultures. Nez tells me, “I feel like when I’m wearing that stuff I don’t necessarily feel like the hottest… but I feel the most excited—like yes, this is what I love.”∎

Words and photos by Bee Barnett.