Experiencing grief at university

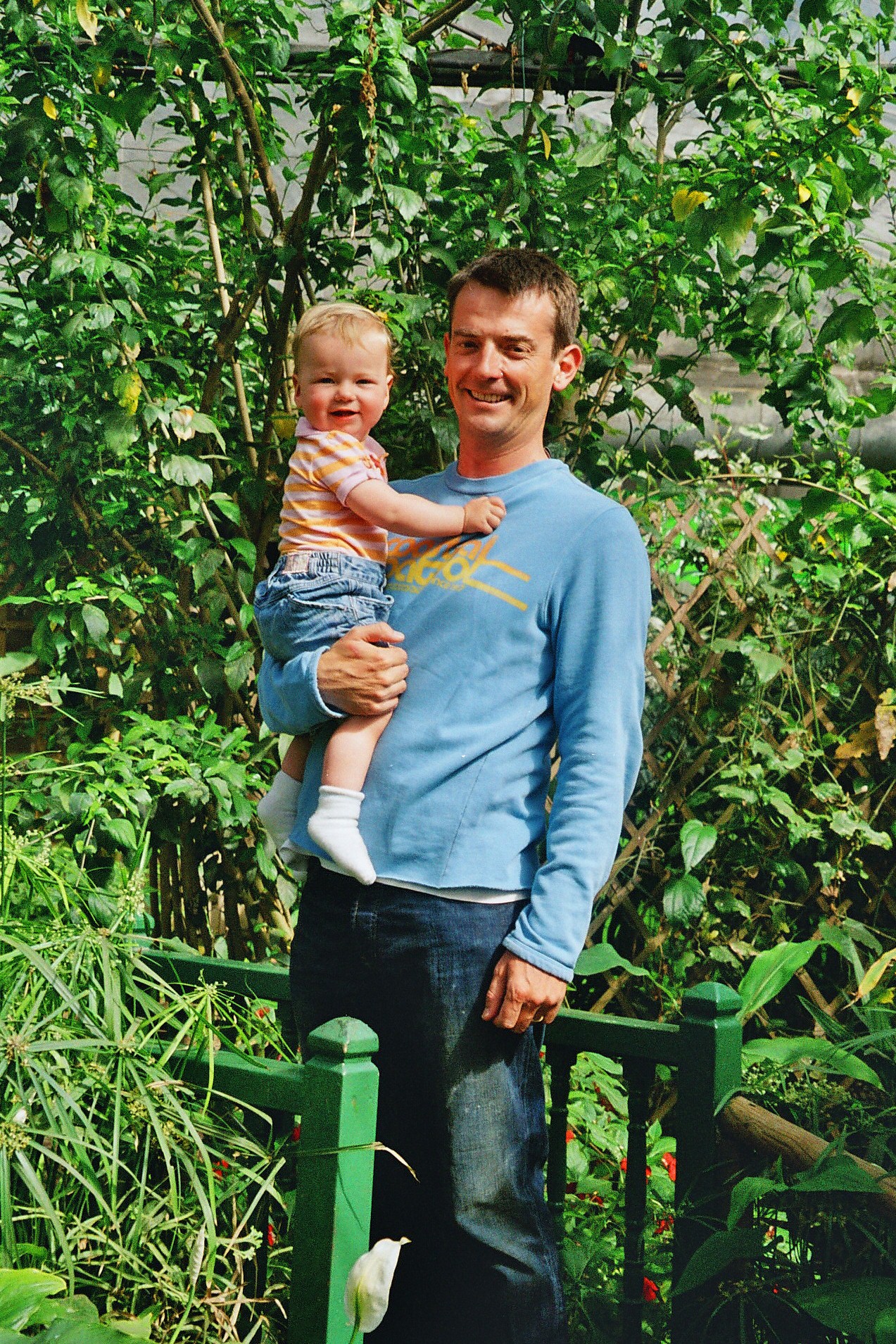

Image: The last holiday with my dad, spent in the Scilly Isles, 2005.

I’ve developed an uncanny trick for telling when spring is on the cusp of summer. It requires very little skill, aside from a keen eye on the advertising campaigns in Tesco Express, Magdalen St. Only last week, having summoned the courage to do my food shop, I noticed (while reaching for the discounted mini eggs) a sign that read ‘GIFTS FOR DAD/ FATHER’S DAY 2024’. I know now, upon my first annual sighting of the relentless over-commercialisation of Father’s Day, that June must only be weeks away. Father’s Day tends to be somewhere between the 15th and 18th of June, personally I find June 17th to be my favourite. I like odd dates; I find a peculiar comfort in their asymmetry. The number 7 happens to be my favourite number and 17 feels like its funny older cousin. The 17th also happens to be the date my father died, so I reckon there is something symbolically gratifying in those two anniversaries coalescing.

My father didn’t die on the 17th of June 2023, just to be clear. He died on the 17th of September 2005. Next year it will be the 20th anniversary. This will be the same year that I will turn 21. I am now over half my father’s age when he died. I should never have outlived my father in this way. I knew him, though not for long. Around 18 months more or less. Grief did not come creeping, it arrived unwelcome and obliterated all in its path. My father was busy living and then all so suddenly he was dead. He had no right to be, only 34 years old. I don’t recall the first few hours of quiet on that Saturday morning, let alone the years that followed. I simply had a father and then I didn’t. That was all.

It’s one thing to grow up with a loss, another to have no memory of the person you are told you have tragically been bereaved of. Here is all that I don’t know of my father: what he smelt like, the ways in which he loved my mother, what a face weathered by age and love would have looked like, what his rage sounded like, his laughter. What I am told is that my father was very smart (I like to believe this because he studied at Oxford too.) He was funny and handsome, a great sportsman, and a kind but often stubborn man. He hated God but he loved sunflowers and the Lord of the Rings trilogy, and me immensely. I am very like my father; my mother often reminds me.

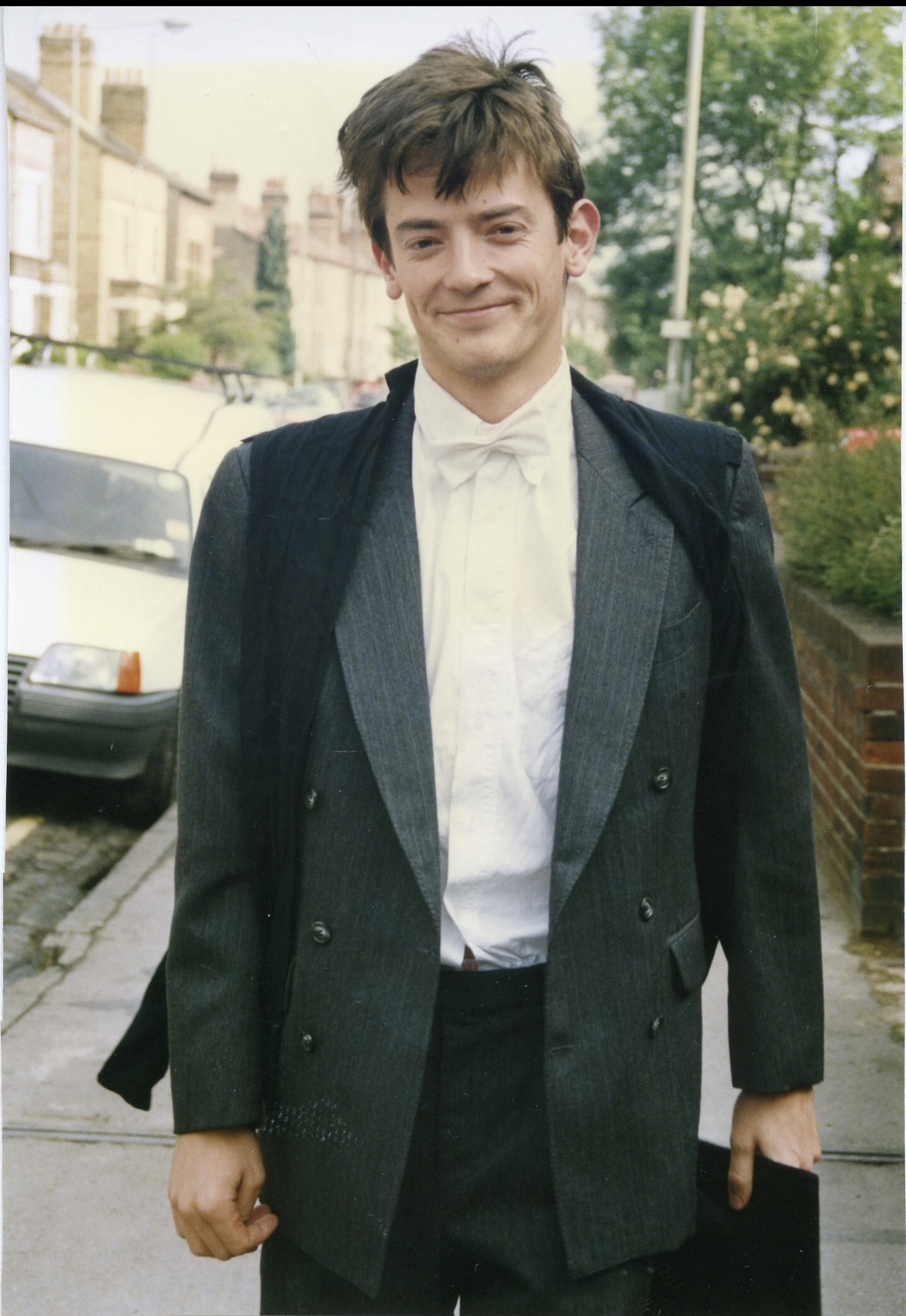

Oxford has grown to become a strange common ground between my late father and me. I know from the few photos I have that he drank pints in the Kings Arms, played cricket at Iffley, adorned the ‘commoner’s’ gown just like his daughter and probably also drank far too much at Formals. I am told by my grandmother that my father was a voracious reader, something I very much try and fail to be. Recently, I made it to Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. Her words have been ringing in my head; “[r]ead, learn, work it up, go to the literature. Information is control.” The older I get, the more I need to know. I need to understand what my father’s death has meant. If it has meant anything at all. Over the years, I have devoured a wealth of resources surrounding childhood bereavement. I could tell you all about the various, speculated stages of grief, particularly why it’s never that simple. I can tell you about the differences between losing a mother and a father, the significance of a homicide vs natural causes and almost everything about the experience of loss between the ages of 1-18. It’s said that the death of a parent dislodges something inside you, especially at a young age. It disrupts the timeline that has been promised to you; that they will be there on your first day of school, the day you try spaghetti bolognese the first time, your first heartbreak, your 20th birthday. I like to believe that after almost 20 years of grieving, I can consider myself something of a professional. At least that I am highly adept at accepting loss, knowing myself, making sense of life’s cruel vicissitudes and all that grief brings with it. Yet, as I wander the cobbled streets of the university my father attended, I have realised I know so little of each of these, most of all, of myself.

Image: Charlie graduating Oxford in 1989.

I have spent my lifetime grieving; it has followed me through my twenty years like a loyal but needy pet. I’ve grieved in my childhood bedroom, the school bathroom, on the riverbank next to my father’s parents’ cottage in the Yorkshire dales. Now I grieve in the city my father spent some of the happiest years of his life in. Each year I have found a different reason to call upon my father’s wisdom. Last year I wished he would tell me how he coped at university, the deadlines, finding the right friends, what I should do when my mother meets someone she falls in love with. This year, I find myself wishing to have a strangely unimportant conversation with my father. I want to ask him about menial things, should I cut a fringe? What colour wool should I knit my next beanie with? Would he like one? At twenty years old what I want more than ever is to know the man who comprises half of me. I would like to know my father.

I have spent nearly a decade resenting Father’s Day and all who participate in it. To celebrate was selfish. To fail to, ungrateful. But, as Father’s Day looms this year, I suppose I’m trying to work out what grief looks like nearly twenty years on. These days I feel I know less than ever, but I think that’s true beyond my experience of grief (God knows how little I know about Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde). What I do know, however, is this: that grief has been an unwelcome gift. In the void of a father’s love, I have relished that offered to me by my friends, in fact, all the people I surround myself with. I know that our knowledge of love is something to be learnt not granted to us. What we know about what we have lost is not dissimilar to what we know of ourselves. I’m reminded of something Max Porter had written in his piercing novella Grief is the Thing with Feathers, that grief is the ‘fabric of selfhood’. My father is all and nothing that I am. He is I, and I him all but for how little we know or will ever know of each other. The grief I have for my father is nothing more than a love enduring. I sense it when I fold the top corner of a book page or declare my atheism. I see it in my friend’s faces when they laugh. I see it in my own.

It is in this that I know, age 20, that I am my father’s daughter.∎

Words by Isabel Raper. Image courtesy of Isabel Raper.