At what cost do we perform the ‘Cool Girl’ aesthetic?

by Violet Aitchison | May 31, 2024

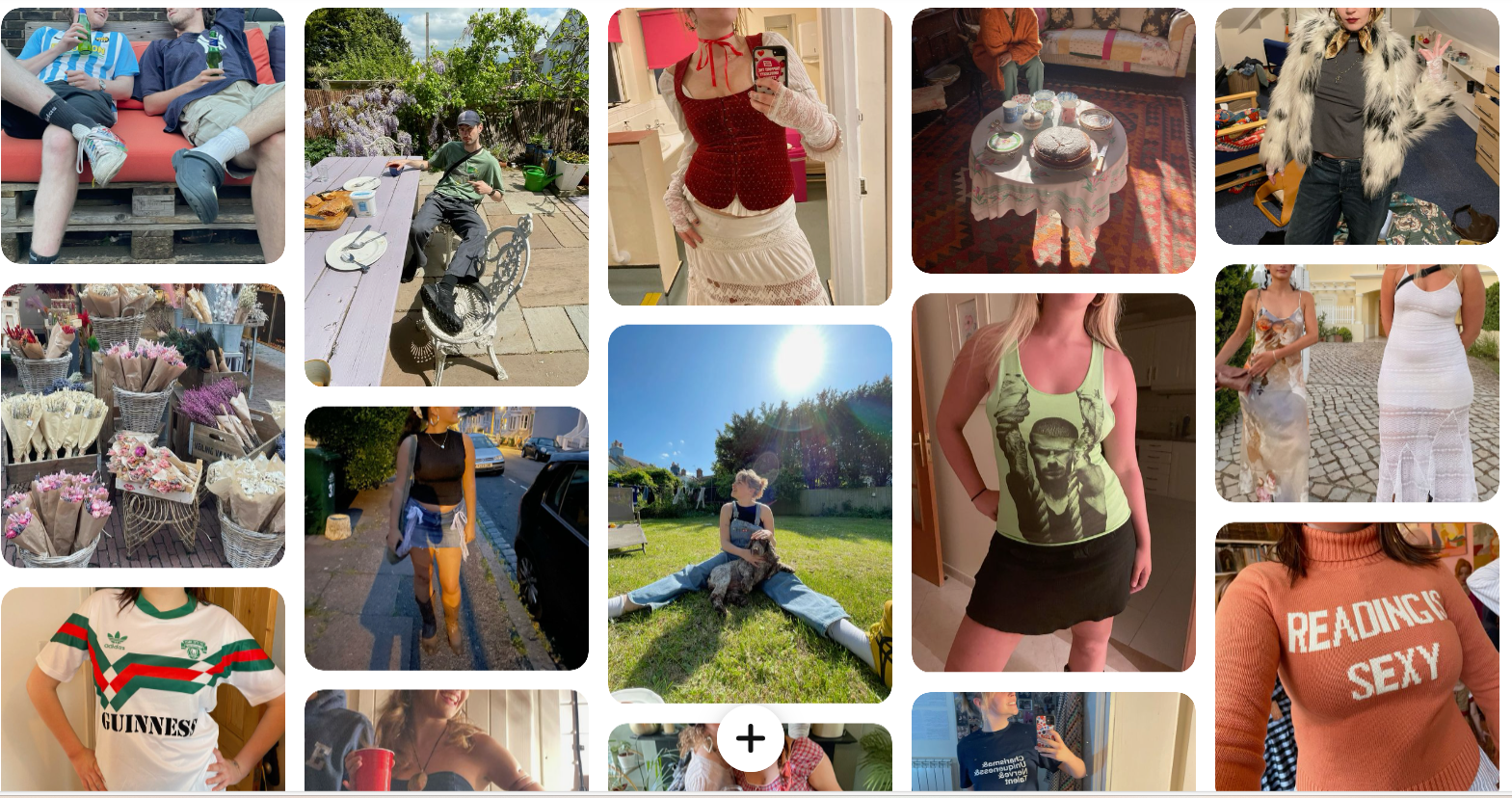

Images: Me, in my best moments of performance.

“The mob wife… is a little more grown up. It’s right there in the name: She’s a wife! She’s not a girl; she’s a woman” claims Harper’s Bazaar. Amazing news for anyone stuck living like it’s the 1950s. Because, as we all know, the defining moment of womanhood is marriage. And, thanks to social media, you too can feel this empowered! Just buy a synthetic fur coat from Amazon, do your smokiest eyeshadow, and take on the traditional role of a mob wife: a mistress or housewife. The godfather (pun intended) of ‘mob wife’ TikTok, Kaya Trivieri (@ktrivz), claims that in its truest form, the mob wife aesthetic is intangible: “It’s an energy, an aura.” To achieve this look, you really must embody and internalise gold old girl-boss, choice feminism. And buy a whole new wardrobe obviously. Be everything at once: powerful yet submissive to your husband; sexy and confident BUT not too much and know exactly where the lines are without asking. Easy enough, I suppose.

‘Mob wife’ might be the latest ‘core’ to capture the attention of social media but in the past couple years we have seen a revolving door of trends including ‘coquette’, ‘clean girl’, ‘Y2K’ and more that aims to fill the social need to define our identities within different categories. I watch my sixteen-year-old sister navigate endless online trends and succumb to depressing pressures, often set by women and men at least double her age; witnessing her girlhood consistently being disrupted. Advocates of trends such as coquette claim they are reclaiming their own girlhood, but this is often at the expense and exploitation of the young women currently navigating their own identities for the first time. Of course, dress however you like. But why is it that we allow influencers and companies to not only dictate the ways we dress, but also define our identities with these rigid aesthetics?

2023’s biggest trend ‘coquette’ is perhaps the best example of this. The term can be traced back to the Victorian period, where it was derogatory slang for a ’seductress’. In more recent times, the coquette aesthetic appeared on 2010s Tumblr in the slightly different form of the ‘nymphet’ aesthetic. Many adolescent girls hopped on the Tumblr trend, blissfully unaware of the term’s problematic associations. The term ‘nymphet’ was popularised by Lolita, the 1955 novel by Nabokov. Lolita follows unreliable narrator Humbert Humbert, who details his perverted obsession with 12-year-old ‘’nymphet’’, Dolores Haze (Lolita), whom he kidnaps and sexually abuses after becoming her stepfather. Before even delving into the actual coquette fashion, the associations alone are enough to make your stomach turn.

And whilst we might feel a long way from 1955 and the sexualisation of pre-teen girls, it was only in 2008 when Australian supermarket chain Woolworths were forced to withdraw a bed design named “The Lolita Midsleeper Combi”. Marketed for girls aged six, many mothers reported outrage at the branding. The store initially refused to recall the bed: they were bemused by the offence mothers had taken. Reports from major news outlets such as the BBC, the Evening Standard and The Times demonstrate how engrained this exploitation of girlhood was and is, with the BBC stating, “a parenting website said it was in “unbelievably bad taste” to give the bed the same name as a novel about a sexually precocious young girl.” To think that even in 2008, major media sources were still victim blaming 12-year-old ‘Lolita’ who was not, as they claim, ‘’sexually precocious’’ but abused and groomed. The world seemed to be more offended by the mother’s outrage than the profiting off a bed associated with a narrative centring paedophilia. This might feel detached from the coquette we know today, but ignoring the history of an aesthetic which has seemingly taken over social media is a slippery slope. Because, simply, central to the inception of the concept of ‘coquette’ is the sexualisation of young women by older men. And this becomes more evident once you explore the look itself.

Step into a coquette closet and you might think you’ve accidentally stumbled into the kid’s section. Bows and ribbon; lace and lip gloss; pink and plaits: the best inspiration for this look comes from childhood pictures of yourself. It encourages a child-like form of hyper-femininity, with a twist of male appropriation. One search of ‘coquette’ on the Urban Outfitters site takes you to 154 different items that are ready to shop. The more depressing items include a ‘Long Satin Bow Clip’ for £12, and ‘Urban Renewal Remade From Vintage Pink Bow Jersey Cami’ sold for £22. But we can surely steady our minds knowing that the president and CEO of Urban Outfitters, 76-year-old American businessman Richard Hayne, has the best interest of ‘Gen Z’ girls at heart. The fashion industry is (unsurprisingly) not the only field to exploit girlhood in this way. The television and film industry has plenty of male directors also taking advantage wherever they can.

Sam Levinson’s show Euphoria consistently sexualises characters such as Cassie (played by Sydney Sweeney) who are supposed to be around 17. The male director plays with pastel colours, ultra feminine clothing, ribbon, and plaits as well as excessive nudity. Sweeney told The Independent, “There are moments where Cassie was supposed to be shirtless and I would tell Sam, ‘I don’t really think that’s necessary here.’’ The show is adored – HBO claiming it as its second most viewed show of all time after Game of Thrones – and continues to profit massively from this oversexualisation of young female characters. Whilst the media might endlessly try to convince us that the coquette core is a great opportunity for young women to lean into traditional forms of femininity, and reclaim our youth, it has been too far removed from the girls and women themselves for this still to be true. And, simply put, it’s another way to categorise women.

If we pull this back to the basics, it’s kind of like a bigger version of the Madonna-Whore complex. The Madonna-Whore Complex is a psychological framework that limits female sexuality through a binary categorisation of women as either virtuous and good or promiscuous and bad. And in this case, coquette is the ‘Madonna’–feminine and sweet–whilst mob wife is the ‘whore’–alluring and confident. Either way, neither seems too appealing. And ‘coquette’ and ‘mob wife’ are only the beginning. The clean girl is yet another brand of aesthetic which aims to set ridiculous standards for young women. The clean girl – Madonna – is sophisticated, effortless, and always thriving.

This aesthetic encourages you to always look and feel your best whilst appearing as if you didn’t even try. Hundreds of thousands of videos litter Instagram and TikTok detailing how you can get the look: most suggesting you adopt a ‘no makeup, makeup look’, ‘slicked back bun’ and ‘minimalistic dress’. TikTok has hailed Sofia Richie-Grainge the queen of the aesthetic and her 2023 wedding was dubbed the ultimate symbol of ‘clean girl’ and ‘quiet luxury’–which can be characterized by understates elegance and refined consumption, emphasising exclusivity and discerning taste without overt displays of wealth. She was (quietly?) adorned in Chanel gowns, a slicked back bun, and paired back makeup. For someone like Sofia Richie-Grainge, who can swap out full wardrobes as quickly as the trends change, her recent stint as queen of quiet luxury is apt. But what these celebrities and influencers don’t tell you is that the simplicity of their looks does not improve the accessibility.

One search about the details of Richie-Grainge’s everyday white t-shirt blue/ jeans combo tells you everything you need to know. Her go-to light denim straight leg jeans go for $250; one pair of her favourite black suede ballerina flats are priced at $745, and a pair of gold hoops to accessorise the outfit will set you back another $350. You are far from a full outfit, and you’ve already spent over $1000. Because, to actually achieve ‘quiet luxury’, you first have to understand the mechanisms of wealth, so you can eventually reject it. It might be branded as the easiest look to achieve, but the truth is, it can only truly be accomplished by a very small echelon of society.

It’s also depressing knowing that it doesn’t even attempt to market itself to men. So many of these aesthetics project and perpetuate completely unattainable standards only reserved for young women. The only aesthetic to really market itself as doubly ‘masculine’ is ‘gorpcore’ which is described as ‘wearing functional outdoor wear in an urban, trendy style’. Supermodels such as Bella Hadid and Kendall Jenner have been described by publications such as Teen Vogue as “sporting the hiking-inspired aesthetic in their own chic, high-end iterations’’. It’s not that surprising that supermodels are the only celebrities spotted in this trend, because the truth is, I’m not sure I know many people that could chuck on a raincoat and still be described as ‘chic’. And it’s not like functionality is a core element of a ‘clean girl’. The clean girl should go to Pilates, drink her inexplicably lurid green juice (and use whitening strips in the evening to remove the tint); make sure she always has a fresh set of acrylic nails and – most importantly – never be seen with as much as a millimetre of hair on anywhere other than her head. In this moment I’m reminded of Amy Dunne’s notorious monologue from Gillian Flynn’s 2012 novel Gone Girl:

“’Cool girl’. Men always use that, don’t they? As their defining compliment: “She’s a cool girl”. Cool girl is hot. Cool girl is game. Cool girl is fun. Cool girl never gets angry at her man. She only smiles in a chagrined, loving manner. And then presents her mouth for fucking.”

And, as it turns out, even in 2024, twelve years after the release of Gone Girl, perfection still isn’t overrated.

I know I’m probably sounding a bit patronising. I myself have subscribed to many of these trends: buying Dr. Martens ‘Mary-Jane’ shoes, occasionally sporting a huge faux fur coat, and attending Pilates classes with my mum during holidays. The fact is, experimenting with this aesthetics can be a helpful way to build up your own style. The internet has been beneficial for many young people from tiny rural towns who want to better express themselves, but don’t know how, or don’t have sufficient influence to do so. It’s great that platforms like TikTok allow exposure in this way. But, for those of us who are older and should know better, it pays to be conscious of our decisions and change the narrative.

The appropriation of girlhood is only one tiny element of the issue with trend cycles, but one you should be well aware of the next time you think about running to buy a closet full of whatever trend will inevitably make its way around TikTok. The days of daily corset wearing might be over, but society will always find a way to tightly lace women in if we let it.∎

Words by Violet Aitchison. Images courtesy of Violet Aitchison.