Won in Translation

Translation is often seen as a necessary evil. It is the imperfect remedy to the embarrassing fact that we can’t speak all the languages, to be swept under the rug and forgotten about. Translation is merely the conduit that allows us to access writings that would otherwise remain mysterious to us. I think ‘access’ has the right degree of clinical-ness here. Translation is associated with precision, and through translation we lose some of the essence of the original, which remains covered and mysterious.

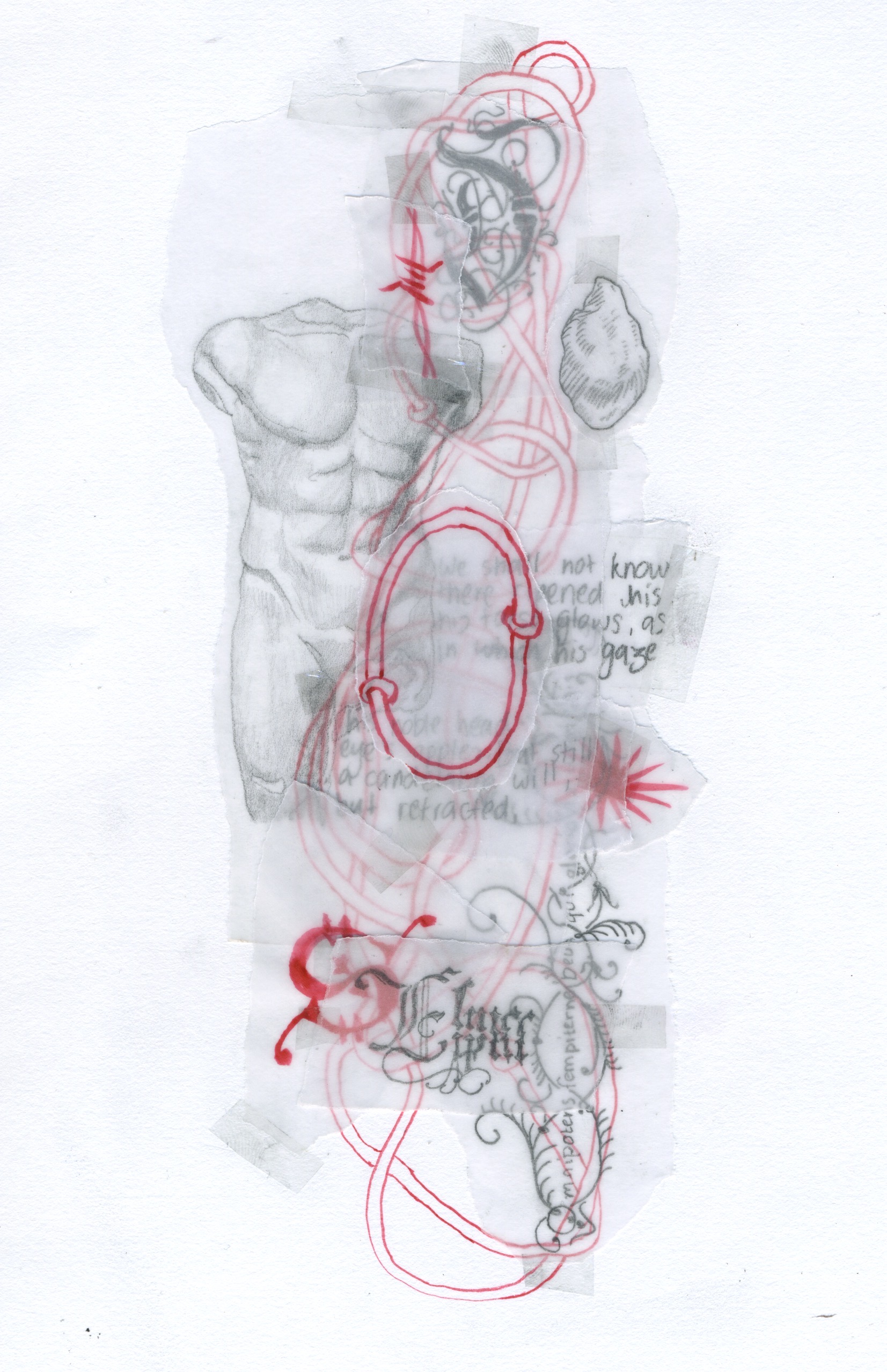

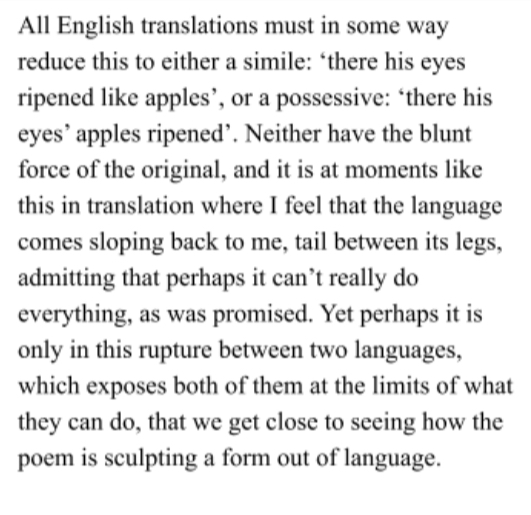

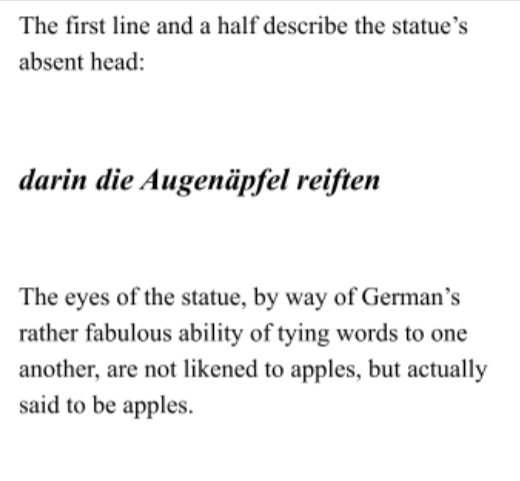

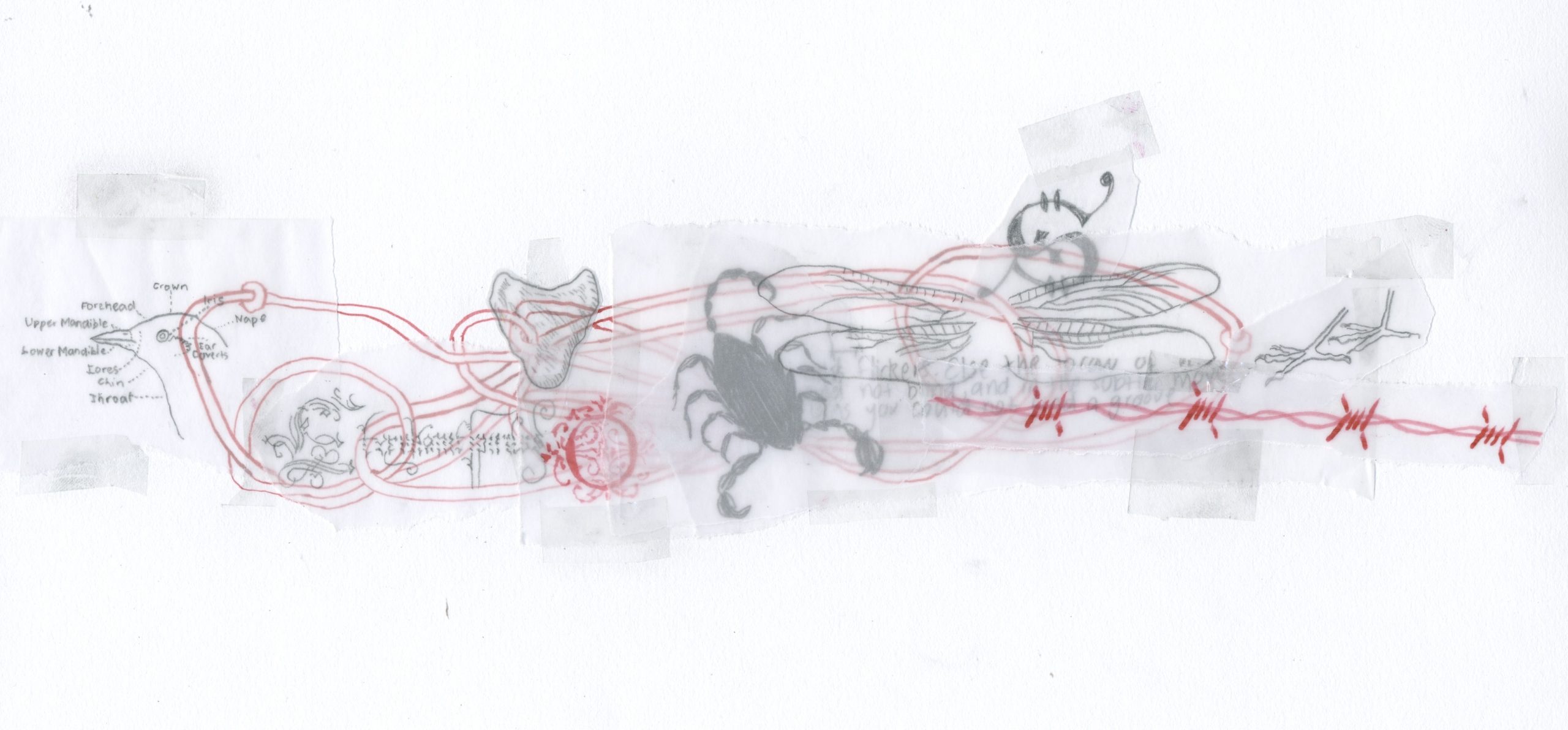

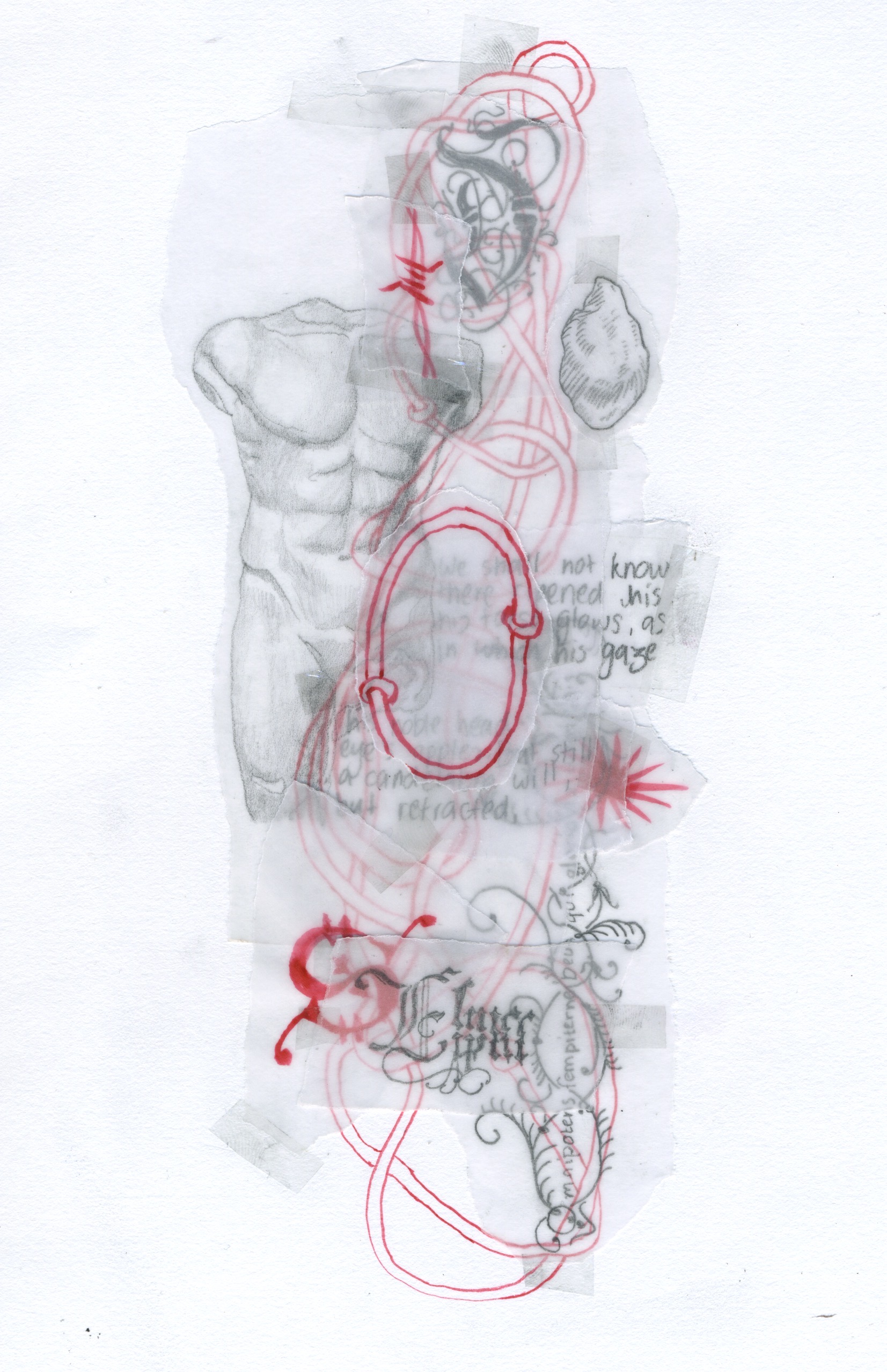

But I think there could be another way of thinking about translation—as a process where a piece of writing is at its most exposed, vulnerable, and honest. Rainier Maria Rilke’s poem, ‘Torso of an Archaic Apollo,’ is a text which might be fruitful in what it can tell us about translation as it is being translated. The poem describes the experience of looking at a fragmented statue, just a torso remaining, uncanny in the way that the headless body seems to gaze back at the viewer. The statue is weird because of the absence that is embodied in the fractures and the sharp edges of its neck, its arms, and its legs. The viewer knows something has been lost. However, this lends it more power, and the statue might almost be able to speak with its strange mouthless voice about translation, as it takes off the clothes of one language and puts on the clothes of another.

As well as exposing limitation, the process of translating the poem can make possible new ideas latent in the original, which reveal themselves when forced to make the leap from one language into another. If I try to maintain the rhyme, problems are certainly caused, but these might also be read as opportunities.

I am, as such, faced with a body of words which seem to be subject to my control. I set to work on it, making it speak again. But as soon as I touch this text, I lose all power: the relationship is suddenly and violently reversed as the text stares back at me, judging me for what choices I will make. Is it acceptable to introduce one’s own words to someone else’s poem? The moment I thought the text had revealed itself to me, I find myself naked before it.

Basically, this is because the translator could be wrong. I could always make this translation a piece of writing that claims to be another piece of writing, which, upon further scrutiny, fails. In this case would I have lied? Anybody reading this would be doing their reading under false pretences. If I am not being faithful to the original, then what is the point of translating it? There is excitement at the possibility of creation tempered by a worry of not living up to the original. Now the statue looks back at me, expectant.

For the reader, the power of any translation is that it comes from a larger whole, like a lost part of the statue. They understand that there is something missing, which in its very absence might give the translation the right to be deemed more suggestive. Rilke repeats the word “sonst” (‘otherwise’) in the second and third stanzas. Otherwise, we wouldn’t read the poem. But otherwise, it wouldn’t have its strange allure in allowing us a glimpse of something we couldn’t have seen.

So much for the reader. I think, as far as the writer is concerned, there is a temptation to see the translator as an impersonator. I worry that in translating I am impersonating, and so that anything I write here is only of derivative worth. I would even to go as far as to suggest that translating comes from a desire to have written things that I have read, and loved. This might seem bizarre, but it is an impulse known to any reader, I think—the feeling of being struck by a phrase, it seeming to speak to something that you know so well, immediately followed by a niggling suspicion (embarrassing to admit) that you could have written it. Or, the knowledge that you could never, would never have written it, accompanied by the desire to know what it would feel like to write it. Feeling this, the translator takes the opportunity to get as close as possible to the experience, to glory in the light of the original author. The translator here is a jealous reader, dressing up as a writer.

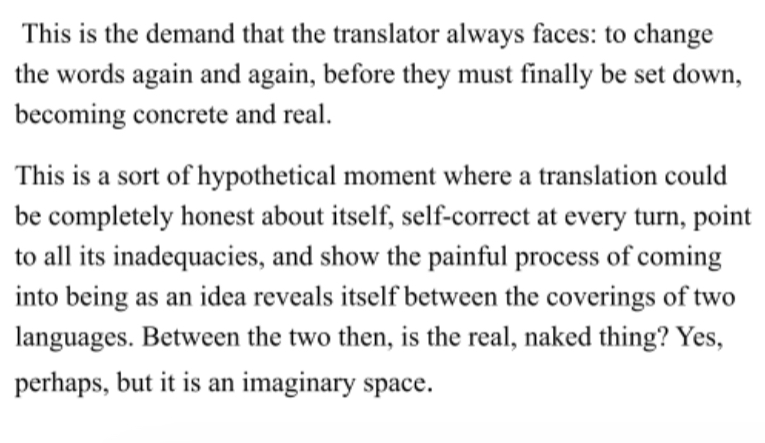

A strange twist on this idea is offered here by the lyrics from the song ‘Dress up in You’ by Belle and Sebastian. The change here from ‘dressing up’ as ‘to dressing up in’, has a particular discomfort to it, forcing you to imagine the body as something that can be taken on or off. Nakedness, a state of exposure, becomes a place of performance too, as though it could never reveal something completely. The translator, in a similarly weird way, is understood to speak with the voice of the original writer, to inhabit their body, briefly. It is quite normal for me to claim that Rilke’s poem begins, ‘We shall not know his noble head’, even though this is, in a really obvious and important way, complete nonsense. Rilke did not write that. The translator is there (in the skin), but normally, we gloss over this because it is odd, and to spend too much time on it would be tedious. But hopefully not here, just for a little longer.

This way of thinking combines nakedness with the idea of putting on a costume. I like particularly the way that it makes me think of the process of revealing something as necessarily involving the hiding of something else. In a translation, if the original text is thought to appear, to reveal itself, then the translator recedes, merely a neutral vessel through whom it passed on its way from one language to another. But, if the text seems to reveal the translator, expose them and their reading, then the original fades into the background, becomes mysterious for the reader of this translation. Translator and translation: ‘We shall not know’ one of them.

Another way of avoiding the fear/accusation of being a mere impersonator might be to think of all translations as suggestions, submitted to the reader with the proviso that all this is said under correction. I have suggested that Rilke’s poem does begin,

But, taken by another, slightly more grandiose mood (not out of spirit with the poem), I might rather think that it begins,

Not huge differences, perhaps, but over the length of the poem, it can be imagined that this would lead to a not-inconsiderable difference in tone. And so, the reader’s experience of the poem would be drastically different.

‘Noble’ and ‘incredible’ might not seem particularly similar words, and this comes down to the fact that the German adjective in this line is particularly evocative: unerhörtes. Reading painfully literally, almost just stringing the parts of the word together to build its meaning, this means unheard or unanswered, like a prayer, and therefore not approved of. But the word has developed more specific sense of singular, and therefore unbelievable, outrageous. None of these English words seem to me appropriate for the description of a statue’s head, lost yet imagined to be magnificent. It is in this moment of consideration and decision, then, that we approach ever more closely to the poem. Rilke closes with an enigmatic comment, as though the statue, having lost its mouth, suddenly speaks to us with a ghostly voice:

Words by Alastair McLelland. Art by Sasha Hardy.