“To Penetrate or to Envelop?” Deborah Cameron On How We Talk About Sex

Have you shagged anyone this term? Maybe you’ve fucked someone, or, God forbid, been fucked? Did you partake in a bit of fifth week love-making? Did you get railed, or did you screw someone?

“One thing that’s changed is people do talk about sex, and they do so publicly”, Professor Deborah Cameron tells me down a crackly WhatsApp line on a dark Wednesday afternoon.

Former Emeritus Professor at the Oxford Linguistics Faculty, Cameron has written extensively on the language of all things sex. She’s even been dubbed the author of the “Penis Paper” (I should say—colloquially, not formally titled), which she wrote in ‘92. Now, she’s retired, but she hasn’t put her pen down: her latest book Language, Sexism and Misogyny is available in all good bookstores.

This piece has been festering in me for a while now. I must confess, perhaps unsurprisingly, that I used to run a feminist literature society with a brilliant friend. Each week we’d pick something new to chew over amongst peers. One week we were having a particularly hard time choosing, and as I was sat in a compulsory and painfully interactive Sex Ed talk (don’t ask), I started to pick up on the speaker’s choice of language. I heard ‘penetration’ an unholy number of times; and started counting which words referred to a female agency, if any. It got me thinking. I was incredibly frustrated that everything we had been taught about sex assumed a power dynamic—to put it crudely, one would either “fuck or be fucked”.

Unable to fall asleep, I came up with the modern-day equivalent of “To be or not to be”: “To Penetrate or To Envelop?”. I curated a coral pink presentation and made my case for the “envelopment revolution” one Tuesday lunchtime.

Now, I want to start at the beginning of ‘sex talk’, but I realise I’m not exactly sure when that was. When did we start talking about sex publicly? Cameron explains “if you think about modern times—if we bracket the Middle Ages—there was a rise of bourgeois politeness around the mid-late 17th century… Things did get written but they circulated underground”. Cameron points out that the ‘60s marked a big turning point: “People talk about the sexual revolution coming in the 1960s and the decades thereafter, which made it much easier and much more commonplace to publish stuff about sex”.

Cameron references the Chatterley Trial of 1960, which, if you don’t know, was when an obscenity trial took place over D. H. Lawrence’s rather raunchy Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Penguin Books already had 200,000 copies printed and understandably weren’t ready to leave Lawrence’s prose to rot away in warehouses, so they hired fiendish lawyers (including E. M. Foster). It took a grand total of three hours to convince the jury to unanimously vote that Penguin Books were, in fact, not guilty of publishing obscene materials. The gavel came crashing down and all was resolved. A landmark case was born.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover sold over two million copies in the next month. Cameron clarifies here, “when we say ‘sex’, I’m not talking about romantic novels, I’m talking about the technical element of it”.

Got it. Let’s get to the “technical element”, then. I’d like to find out if men and women broadly talk about sex in the same way. We often tend to get the impression that some men, when in same-sex groups, will use language that makes their sexual partner seem submissive or passive. Exhibit A: “I fucked her”, or “I screwed her”, or (we even lose a personal pronoun here), “I tapped that”. Now, I’m not saying women don’t say these phrases too, but there seems to be a stereotype that the feminine way of talking about sex is less dominating, and a little more focused on a partnership. Exhibit B: “We fucked last night”, “We slept together”.

Cameron carefully agrees that “there are stereotypes to which there are probably many exceptions”. One of these stereotypes, she tells me, “is that men are visual, and women are all about words: women get turned on by erotic prose but men need the dirty pictures.” She chuckles now, and cheekily notes “I’ve met plenty of women who like a dirty picture.” Don’t get me wrong, I usually pride myself on being fairly relaxed in these kinds of taboo conversations, but Cameron certainly has the upper hand. She’s been writing and talking about the sociolinguistics of sex since the ‘80s. Well, we’ve made it past the first awkward five minutes, thank God, and we’re already chuckling about female pleasure.

Speaking of female pleasure, Cameron is frustrated with how the word “sex” tends to be viewed: “There’s a long-running problem about ‘sex’ being defined as the set of practices which men find most pleasurable, and for women they are unsatisfactory… I’m talking about intercourse, penis in vagina, fucking”. For a long time, feminist activists have spoken about “how most women can’t get an orgasm just from that—they need clitoral stimulation”. Words like “foreplay” are particularly noteworthy to Cameron, because it implies that “turning a woman on is what you do before the main act”. Cameron believes that if you asked a sample of people to define sex, most would define it solely as intercourse: “We think of it as the man plugging away in there which starts when he penetrates you and ends when he comes”. I’ll admit my eyebrows raise slightly.

I want to know more about how our anatomy is named, and I’m shocked by what Cameron has to say about this. “A lot of sexual terminology is in Latin [and] when you look at what it means it’s a bit of a taker-aback”. For example, anatomists still use derivatives of the word “pudendum” to talk about external genitalia regardless of sex, which Cameron tells me translates as “‘thing to be ashamed of’”, coming from the verb “pudere – to be ashamed or to make ashamed, it’s the gerundive”. Of course, medical students don’t typically know this when they’re learning about the pudendal nerve, but as Cameron rightly asks: “Why are we still talking about a woman’s shameful parts?”

Even the word “vagina” can be traced back to meaning a “scabbard, the place where you sheath your sword”, she says. (The “sword” being the “penis”, if you hadn’t got that). I already knew about the “scabbard” situation, but not the “pudendum” palaver, and I’m curious to know what Cameron thinks the next step should be. Are we aiming to stop all use of these terms? She tells me “there is a world committee that decides on official anatomical terms”, and while they did get rid of “pudendum” (not just because it’s sexist, but because it’s “extremely vague” and not even medically useful), they kept the “pudendal nerve”. Cameron notes that these debates “bring out some very ancient attitudes”; for example, she remembers a debate on whether “shame is another word for modesty, and modesty is positive”.

“Since when was it a good idea to locate people’s virtue in their genitals, and in the concealment or non-use thereof?”, she asks.

When Cameron was working in the US, a group of students told her that when they were “by themselves, usually in same-sex groups”, they’d sit round in a circle and “come up with as many words for the penis as they possibly could”. Cameron asked them to record this exercise the next time they did it. She tells me she wanted to analyse the terms her students used to figure out if there were any underlying metaphors. Cameron admits: “I got formally complained about to my department after publishing it”.

So, what were the findings? “One very clear metaphor was that the penis was personified: it was like a separate person. It was kind of feral and strong”. Other metaphors included things like “machines, meat … tools, weapons”, which suggested to Cameron that “sex was being conceptualised in terms of power and conquest – not intimacy or affection or mutuality – it was all about the penis getting in there and conquering.” If you’re curious and want some light holiday reading, it’s called Naming of Parts. (And, in case you hadn’t clocked, this is the one and only “Penis Paper” I referred to earlier on.)

Other linguists would follow suit later on and tried to analyse different terms for female genitalia, but, as Cameron puts it, “that was just a mess”. Scathing. The Vagina Papers (as coined by me) found that female genitals tend to be conceptualised “as a hole, a trench, something dirty”, but – and this is fascinating – “there was no personification as a conqueror, or indeed as the submitter”. Ultimately, “it was all about the disgustingness of the female genital”.

All of this is fascinating, but I’m conscious our conversation has strayed into the abstract. It’s easy to speak to like-minded people and really dig into the small print. Don’t get me wrong, Latin etymology is fun, but I want to understand how these words and phrases actually affecting us, if at all. Perhaps we don’t really think about them enough to have any consequences. I mean, is the word “foreplay” really reinforcing our sense of the female orgasm’s unimportance?

Cameron walks the fence on this one: “I don’t think that when people use the words there’s an instant shock”. But, she reminds me that most of the time “it’s not so much etymology as it is metaphor”, and “the accretion of these different uses does actually send a message”. She leaves me with a hard pill to swallow: “It does tell us something about what the conceptual scheme is that people are imposing on the activity of having sex”.

So, next time you tell your friends about all that sex you’ve been having; I dare you to think about the metaphors you’re using. Because maybe, just maybe, you enveloped them this time.∎

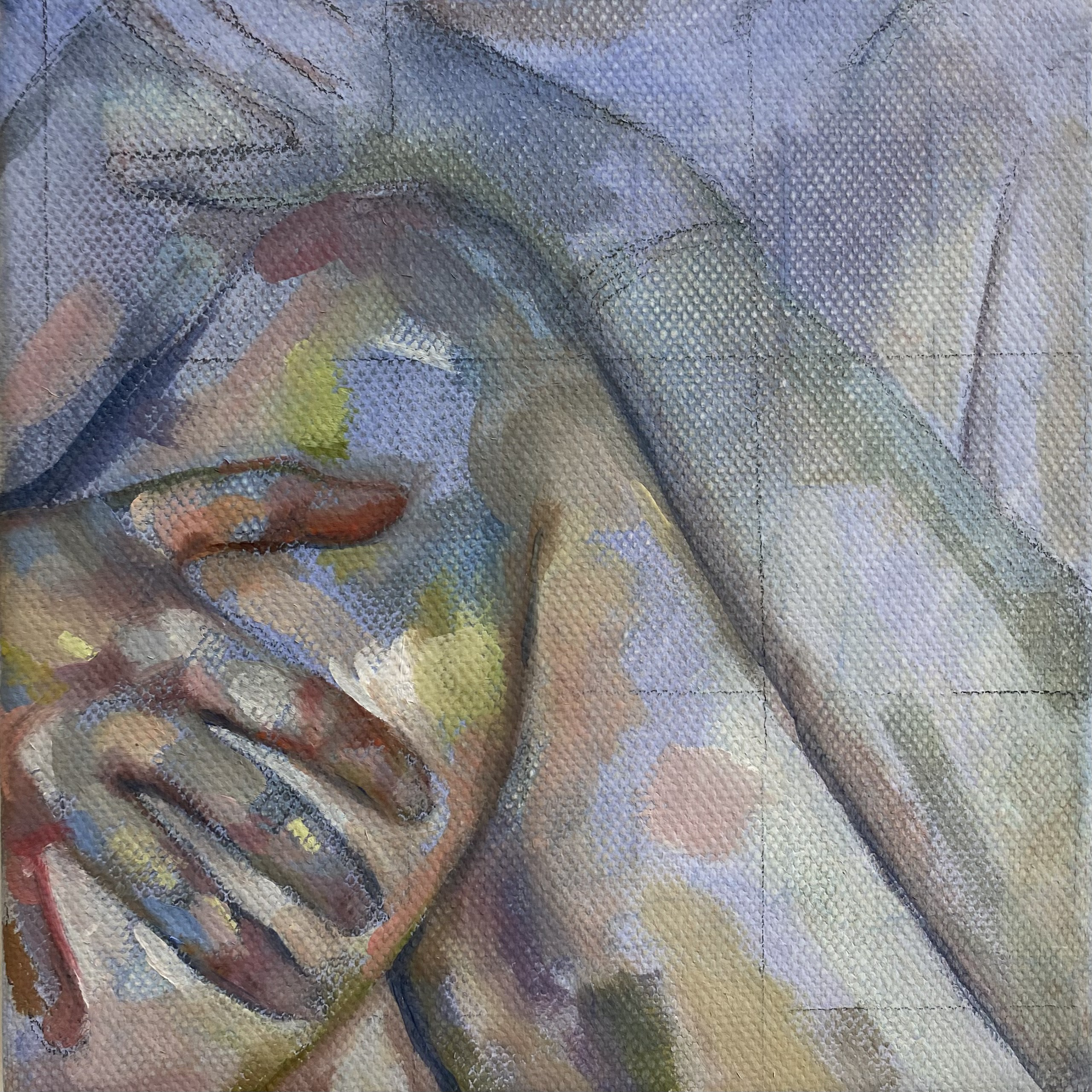

Words by Bella Gerber-Johnstone. Art by Sasha Hardy.