There’s Nothing Abstract about the Climate Crisis: An Ecological Case against Conceptual Art

by Izzy Walter | February 21, 2024

It’s often been said that all art is political. The case is compelling and it’s one that I subscribe to. All Art is personal, the personal is political, and, in a world of fake news, it’s important to interrogate the agenda of media we consume. Luckily, our ever-impartial prophets at the BBC are always ready to take up arms against misinformation. The final episode of Attenborough’s Saving Our Wild Isles was cut from the series by the corporation. Fearing right-wing backlash, it was deemed too ideologically driven for broadcast. Phew! Another close escape from the lefty climate conspiracists. Britain can keep its head in the cosy sand another day. Except, the excised episode isn’t riddled with the harrowing reality of pastoral farming, or the disturbing statistics on wildlife loss. David Goulson, Professor of Biology and author of Silent Earth, criticised it for not going far enough. He described it as “deliberately uplifting and overwhelmingly positive”. Rightly, Goulson implores Attenborough to use his privileged position and “persuade the BBC to commission the hard-hitting, kick up-the-arse documentary we really need”.

In this instance, assuming the inherently political character of visual art is important — it allows us to probe the bias that underpins creative decisions from media outlets. However, I worry that ascribing an ideological status to any purportedly ‘ecological’ artwork has removed the pressure on mainstream fine art to engage effectively with political issues. Whilst documentary deals with real-life images and tangible events, post-modern art’s vendetta against the figurative risks becoming irresolute, impractical, and ultimately illegible. At this point, the climate movement simply can’t afford to deal in good intentions.

Richard Long and David Nash are two seminal figures of British Land Art, strongly associated with the British ecological art. Long is well-known for A Line Made by Walking (1967), where he walked repeatedly across a field and photographed the trail of flattened grass with ethereal results. Nash also makes elegant alterations to landscape in his work Ash Dome. In 1977 he planted a ring of twenty-two ash trees and diligently guided their development so that they rose to form an enclosing canopy. Of course, there is value in this type of work – namely therapeutic — but I don’t buy that anyone’s walking away, jumping on their computer and sending a letter to their MP. These works are too idyllic to spur practical change and certainly too abstract to instruct it – ironically, the very change needed to protect their materials.

The wider problem here is that the bread and butter of conceptual art is simply ill-equipped to deal with climate change. Its entanglement with abstract theory and survival on lofty absolutes cannot even begin to approach the issue’s administrative complexity. The existential density of the climate crisis is a serious barrier and art must step up to the task.

I don’t believe the fault of the climate crisis should fall at the feet of the individual (as the infamous BP Carbon Footprint campaign would have us believe), nor do I think all contemporary art fails to productively engage with the topic. I am simply imploring the art world to re-evaluate its love affair with abstraction in the face of imminent disaster. There is nothing abstract about climate change. It might be a different story if, across the board, fine art was under pressure to deal directly with ecological threats, but ‘environmental’ art persists to remain a segregated category.

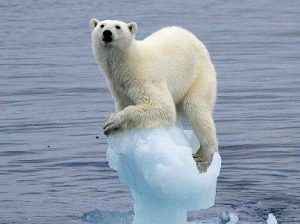

Take for example Olafur Eliasson’s globally-acclaimed Ice Watch. Mark Godfrey (Tate Curator) commended the artist for “[making] this crisis of climate change tangible for people because it gives [it] a physical experience and puts people really in touch with something that usually you couldn’t imagine”. Eliasson’s work consists of three ice blocks and was reiterated at three locations around London. Imported from a Greenland fjord, at ecological and financial expense, the choice to place this artwork in London, the seat of English government, and align it with ecological activism feels unconvincing. Does Britain not have enough issues of its own without outsourcing? Yes, the UK is one of the top emitting countries (and that’s just territorial emissions) and yes, the effects of those emissions are rising temperatures, melting ice caps, and rising sea levels, but the work doesn’t actually clarify that relationship. Its focus on the material landscape of a different continent is rendered alien and ambiguous in Trafalgar Square. What about those issues closer to home? Those that might signify more immediately? Just a few that spring to mind include the pollution of the Wye River, the government’s repeated approval of peat or the effective ban of onshore wind turbines. But maybe that would be too political. According to Godfrey, Eliasson has also “inspired world leaders”. I suppose these are the same “inspired” leaders who have allowed more carbon to be released from underground stores in the last 28 years than in the 75 before their first COP summit in 1995? I have no doubt that these so-called leaders leapt at the chance to proclaim their admiration for an artwork that deploys the same abstract vocabulary as their own immaterial promises.

Eliasson’s puddles are not going to cut it and, whilst I truly enjoy the work of Nash and Long, at what point do these idyllic works fall into the same category as Attenborough’s documentary? Pandering to the ageing Brexiteer’s fantasy — that Tolkienian albion of the good old days where rivers ran clear, biodiversity abounded, and, as John Major said in 1993, “old maids [bicycled] to Holy Communion through the morning mist”. Isn’t environmental romanticism the real propaganda?

On a more optimistic note, we need to think about what effective, truly radical, ecological Art looks like. I nominate Richard Mosse’s exhibition, Broken Spectre at 180 The Strand. In his latest exhibition, the photographic artist uses multi-spectral infrared sensors to show the destruction of the Amazon rainforest in alien, dystopian colours. Far from the green and pleasant countryside of ecological romanticism, the garish illusory colour distortion of his photographs is disconcerting and surreal, and the black and white film in the following room puts up a similar resistance to the idealizing gaze. In other words, it’s closer to the truth. Reviews described it as “deeply political and distressing”, portraying “the amazon as a devastated, barren, singed place . . . The whole thing is brutal, overwhelming, affecting, disgusting, heart-breaking, and utterly brilliant”.

This is precisely the sort of art that David Goulson is writing about: “the hard-hitting, kick-up-the-arse documentary we really need”.∎

Words and photography by Izzy Walter.