The Farce of By-Elections

It’s been quite a year for by-elections. Last month there was double trouble, with Nadine Dorries and Chris Pincher both being thrown out of their seats in a single day. In July there was triple trouble, with three by-elections in one day, including the final exit of Boris Johnson. In all, at the time of writing, we have had seven by-elections in 2023.

Political implications aside, there is something quite comical about by-elections. If you’ve had a chance to see one up close, you’ll know. The canvassers slamming down your door, the smears flung from left and right, the meetings in assembly halls, the hecklers, the posters, the journalists; for a moment during all of that chaos, the town seems suddenly to matter.

It’s obvious, then, why by-elections are such a fail-safe joke. In fact, they have been a staple of humorous writing in this country for centuries. In cartoons and satirical papers, of course, the view has always been the same, but in literature and film it is even more remarkable. A popular view of by-elections as essentially farcical remained unchanged over at least two centuries, and this I think is worth examining.

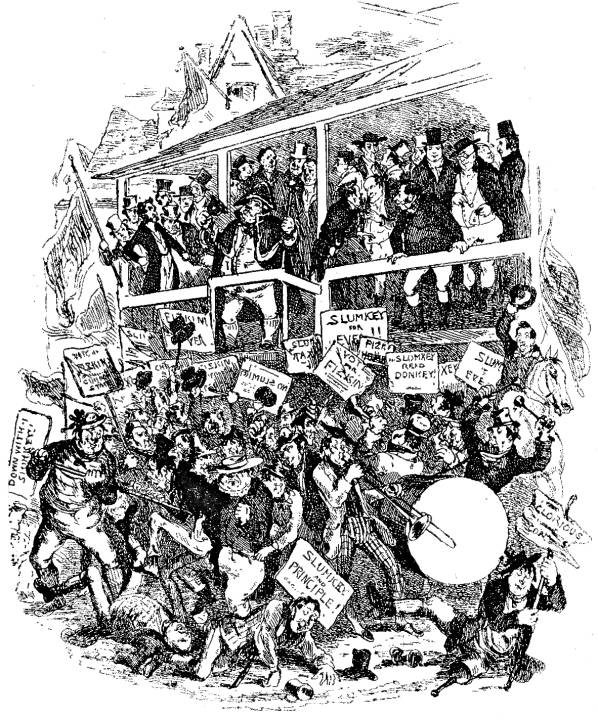

In the 1830s, Charles Dickens centred a chapter of his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, around a by-election. The date is significant. At that point, although the old party system of Whig and Tory was still a recent memory, the dominant two were Whig and Conservative. Dickens had, in younger days, been a Parliamentary reporter, so he understood the serious political impact of by-elections. But he instead spends the whole chapter ruthlessly making fun of them. He begins by setting them on an equal footing: “Now the Blues lost no opportunity of opposing the Buffs, and the Buffs lost no opportunity of opposing the Blues”. His objective position is an advantage, because he can devote equal attention to both sides.

The campaign itself is soundly ridiculed. Each side has a propaganda machine which spends more time slagging off the enemy than disputing points of policy. The candidates, Slumkey and Fitzkin, try all sorts of things to win the townsfolks’ favour, including kissing babies. Eventually, supporters of both parties form mobs and there is a violent clash. A scene of dialogue between Mr Pickwick, his friends, and the mob, is worth quoting in full:

‘Slumkey for ever!’ roared the honest and independent.

‘Slumkey for ever!’ echoed Mr. Pickwick, taking off his hat.

‘No Fizkin!’ roared the crowd.

‘Certainly not!’ shouted Mr. Pickwick. ‘Hurrah!’ And then there was another roaring, like that of a whole menagerie when the elephant has rung the bell for the cold meat.

‘Who is Slumkey?’ whispered Mr. Tupman.

‘I don’t know,’ replied Mr. Pickwick, in the same tone. ‘Hush. Don’t ask any questions. It’s always best on these occasions to do what the mob do.’

‘But suppose there are two mobs?’ suggested Mr. Snodgrass.

‘Shout with the largest,’ replied Mr. Pickwick.

Volumes could not have said more.

The humourists of the twentieth century followed the same pattern. Something very similar to Dickens was attempted by Rudyard Kipling in ‘The Village that Voted the Earth was Flat’ (1917), which, though not strictly a by-election story, still pokes fun at a village that is torn into confetti by a media campaign of ridicule against the local MP.

The humourist Saki, too, in a 1919 story called ‘Canossa’, tells the story of a by-election candidate who goes on trial for blowing up the Royal Albert Hall. The government, not wanting to lose any by-election votes, makes sure his sentence is reduced to a single week; as soon as the week is up, however, the candidate refuses to leave without a brass band; so, a brass band is hired and, just in time for the vote, he is released. He loses the election. Here, again, is the same dysfunctional process of government, the same lunacy over an election result, the same idea of a by-election result being prioritised over everything – literally everything – albeit with a much more extreme example than in Dickens.

Even P.G. Wodehouse – who is agreed to have been the finest comic writer of the twentieth century, and was about as apolitical as they come – doesn’t refrain from poking fun at by-elections. He chooses as his medium a 1923 story featuring one of his lesser-known characters, a sociopathic but loveable sort of con artist called Ukridge. In ‘The Long Arm of Looney Coote’, Ukridge helps to arrange an old schoolfriend’s by-election campaign. Here, too, the comic potential of the scenario is fully exploited. Speeches are made. Babies are kissed. Potatoes are thrown. Angry mobs attack. Propaganda wars start, with songs and posters as each candidate tries to sabotage the other.

Two things are remarkable in this Ukridge story. Firstly, the sheer chaos of it all. Secondly, the fact that – in almost a century of political development since Dickens wrote The Pickwick Papers – absolutely nothing has changed. The by-election turmoil is identical. The mocking, detached narrative is identical. Either story could be swapped into a different century and still be just as relevant.

The advent of film didn’t get in the way of by-election comedies either. With the end of silent era, cinema, which until then had been monopolised by slapstick, now became habitable for more advanced forms of comedy. The 1930s unleashed a stream of political satires, many of them reliant on the by-election trope.

One of these – a quota quickie called A Political Party (1934) – was a vehicle for an unfunny comic actor called Leslie Fuller. The plot is quite straightforward: A chimney-sweep decides to run for Parliament against a local aristocrat. Today this film is probably most noteworthy for depicting the growth of social mobility – a chimney-sweep in Parliament would have been impossible even a decade earlier – but it also makes use of the classic by-election tropes. The polarisation of the town into meaningless groups (“socialism, communism, rheumatism”); the throwing of potatoes at candidates; the underhand schemes to sabotage the opponent; are all topped off with a romance plot involving the chimney-sweep’s son and the opposition’s daughter.

This entire ludicrous parade marches along onscreen just as it did through the pages of Dickens, Kipling, Saki, and Wodehouse. In the end the chimney-sweep does win; but no sooner has he taken his seat than a general election is called; and, refusing to undergo “the whole damned thing” again, he quits.

In Storm in a Teacup (1937) there are some vaguely similar ideas: a hypocritical MP is ridiculed (Pickwick Papers); a trivial media campaign goes national and erupts into provincial life (‘The Village that Voted the Earth was Flat’); and the hero marries the MP’s daughter (A Political Party). Even more in the classic tradition is the film Old Mother Riley, MP (1939). Here, again, the social context is unique – barely twenty years earlier, a woman would not have been able to stand for Parliament – but the depiction of by-elections is the same as ever. Again, for all the contemporary upheavals in society and politics, the by-election pantomime remains the same.

The most representative by-election comedy of the post-war era is Launder and Gilliat’s Left, Right and Centre(1959). By this point in history, much had changed in politics. For instance, Conservative and Labour had replaced Conservative and Liberal; and the “post-war consensus” was in full swing. Yet the film begins on the same objective note as Dickens’ piece from a hundred and twenty years earlier. An opening narrator tells us: “Whereas the Conservative philosophy is the exploitation of man by man, with the Socialists it is exactly the other way around”.

What follows is a traditional by-election comedy with all the usual trappings, under the guise of a unique plot about two opposing by-election candidates who fall in love with each other, as their campaign managers work together on schemes to rekindle the rivalry. There is the usual campaign drive, the usual hostility of the locals, and the usual descent into a shouting match and a mob. On the whole, the exact same events could have been taking place a century earlier or later.

One scene is especially noteworthy. The Labour Party office has called a certain political giant to give a speech supporting their candidate. This political giant accidentally ends up at the Conservative Party office, where he gives a speech on party principles and is applauded; then he is taken back to Labour HQ, where he makes the exact same speech, and is applauded just as keenly. From this scene anyone can gauge that our politicians today are hardly unique in being considered “as bad as each other” or “lacking in principles”. Surely one of the great things about Parliamentary democracy – and there are many – is that nothing ever changes…

To conclude, then, there is one thing which, across centuries of different political contexts, remained consistent about the view of by-elections. It is the very quality which, in more recent times, we no longer apply to by-elections: a sense of the absurd. In the old view, neither political party is taken seriously. The whole by-election ceremony is not only idiotic but openly acknowledged as such. Peaceful villages become the scene of riots. Friendships are torn apart. Careers are ended. But it’s all such tremendous fun. The general view, held by everyone from Dickens through to Launder and Gilliat, can be summed up as: “What is the point of these damned by-elections when, long after all these policies are gone, others will be fighting this silly little campaign all over again?”

This, I think, is the right attitude to adopt. Not towards politics as a whole – I and many others may still feel strongly about politics – but at any rate towards by-elections. Today, we can acknowledge that there is genuine need for political change, felt by many people who have no channels to express their concerns other than through by-elections; we can acknowledge this while keeping good-humoured about the by-election ceremony itself. By-elections and their results are of course very serious matters – but it will always help to take the tradition with a pinch of laughing gas.∎

Words by Hassan Akram. Featured image courtesy of The Victorian Web (https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/phiz/pickwick/14.html).