Emerging Blinking: ‘Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality’ at the Ashmolean

The Ashmolean’s Sainsbury Gallery is rarely so atmospheric. Dark walls loom over codices and drypoint, partitions make the rooms themselves maze-like, and the space is given a feeling of hushed silence – normally. On my third visit, it’s Summer VIIIs, and viewers huddle in the cool away from the sun. The Ashmolean is focused on a very different outdoor activity: excavation. As we start to examine the actual material from Crete, the second room is lighter, blue, and by the final room, we are bathed in the clear light of archaeological clarity, a white 3D-printed reconstruction taking centre stage. It’s an effective analogy for the exhibition’s structure: the scraping back of layers encrusted over the story of Minoan Crete. It also places Labyrinth in the smaller category of exhibitions that work backwards in time. We are offered three very different courses as we progress.

The Ashmolean is well placed to host the exhibition, as Sir Arthur Evans was the gallery’s director during the excavations, and the curator, Dr Andrew Shapland, occupies a post named after him. Knossos is one of the few survivals of the Mycenaean Bronze age, a culture onto which much of Greek mythology – including the stories of Theseus and the Minotaur – maps. The stories are told in Ancient World as much as 600 years later.

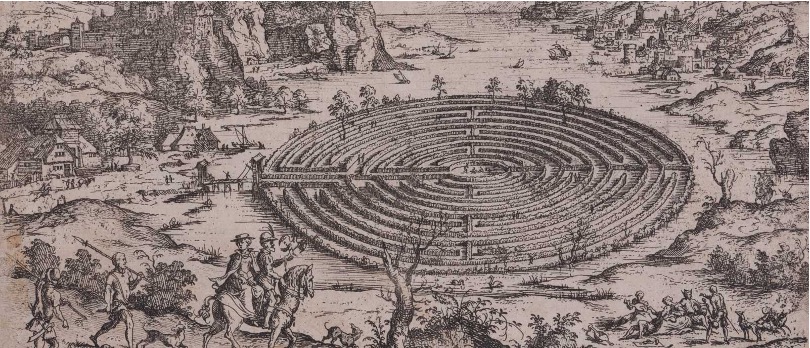

The opening room’s maze of candlelight and prints on black walls feel like a fantasy tunnel of the Western imagination. Here prints by Picasso jostle with late Roman sculpture (a centrepiece with a fantastic flaring nostrils), Athenian vases (with an excellently crisp tondo in a cylix) and 16th century maps (each with a different postulated location for the eponymous maze). A centrally placed vase is comic-strip-like: first Theseus levels his sword, on the other side he plunges it in. A thoughtful touch came from some papyri from Oxyrhynchus, detailing Cretan presence in the Iliad and a synopsis of Euripides’ lost Theseus. The mythmaking reaches back into antiquity: Cretans themselves adopt the labyrinth as part of their iconography on coins as early as 300 BC.

But the labyrinth doesn’t just belong to the ancient world. Etchings show it as a Christian allegory in Boethius. Wobbly medieval maps abound – the crucial maze always changing location – and are eventually replaced by Spratt’s more painstaking 17th century attempt. Nor does the story mean the same to everyone. Across the wall from the Picasso (where the minotaur is the feral part of his soul), a print from Michael Ayrton’s series shows it tenderly, learning to walk.

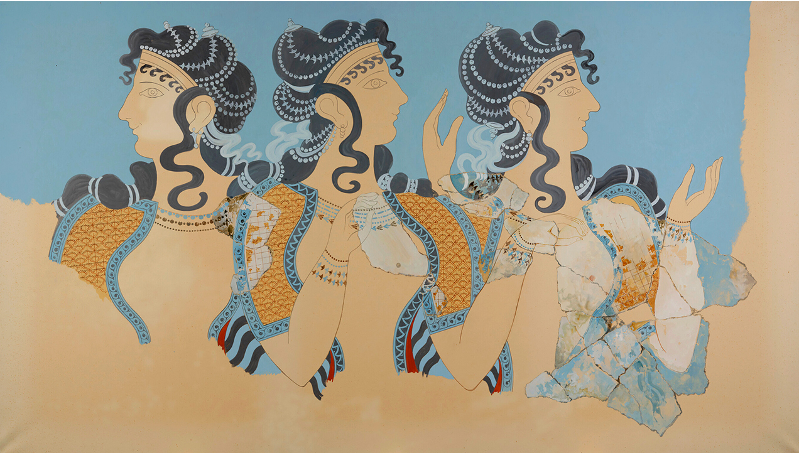

Enter Evans and the archaeology. Appropriate mention is made of Minos Kalokairinos, who first discovered the site, and we are offered the key conceit: the palace is the labyrinth. The evidence for this is both archaeological (the unearthed floor plan sprawls well over 100 rooms) and linguistic (“Labyrinth” can be crowbarred to “house of the twin axes”, a motif appearing among the ruins, and in the exhibition). We have Evan’s handwritten notes, and an Egyptian statuette that allowed him to date the palace complex and infer trade routes. Stylish vector-style columns line the upper walls among the blue, while Tetris shapes float above the viewers. Olive trees, dancers, blue-skinned youths and bulls litter the frescoes – and the watercolours of reconstructed views are deceptively lovely, even if alternative versions keep you alert to their fictiveness. Crowds are sketched-in loosely as if by Quentin Blake. The lighting was perhaps a little dim to do justice to the riot of colour they offered. Additional highlights are the octopus-vases (some however offer a stingy seven tentacles). Their brilliant, startled eyes have always made them a personal favourite. The pottery is a delight – particularly one covered in tendrils imitating stone veining. This is not only a relic from the past but imaginative design that would put Clarice Cliff or Grayson Perry to shame. Several examples are shown next to the Ashmolean’s watercolours of the same vessels, a pleasing call-and-response.

The searing white of the third room heralds the arrival of modern techniques. We are introduced to more recent discoveries, both pre- and post-Minoan, digital photoplastry, and a centrepiece reconstruction with Evan’s additions thoughtfully removed. He rebuilt parts of the site in line with his reconstructions. Even with correction of Evan’s hypotheses, of course, the conceit is ironic. We know much less about the Minoan Palace culture than we do about the Minotaur in the Western imagination, and while Shapland would like us to emerge into the light, the evidence, although real, is a murkier path to follow than the history of its reception. There is also a video installation by Elizabeth Price, a welcome addition if not as magical as the recovered palace.

One whimsical element is allowed into the final survey: Michael Ayrton’s series of minotaur prints return: his minotaur now able to walk and gazes at its reflection in a polished shield. An appropriate final image.

Words by Oliver Roberts

Image credit (in order):

- Knossos Web Banner, 2023, © Ashmolean Museum

- The Cretan Labyrinth, 1558, after Mathjis Cock drawing © Ashmolean Museum

- Watercolour restoration of Ladies in Blue Fresco, undated, by Émile Gilliéron père (1850–1924) © Ashmolean Museum