Hide and Seek with the Brain

The brains of today remind me of hamsters on wheels: forever playing catch-up, running from one day into the next, set on rebuilding themselves. At times, stretching themselves awake in a baby, and later, spreading across the sky. There are two types of people who can teach you a great deal about this densely packed bundle: Ones in whom it is forming and those in whom it finds itself unravelling. I remember the first time I heard Dida’s speech start to slur. I watched as parts of the woman who raised me were unwinding like leaves in autumn. One of the first names to go was the one she had chosen for me: Spa-tea-kah, with all its clashing consonants.

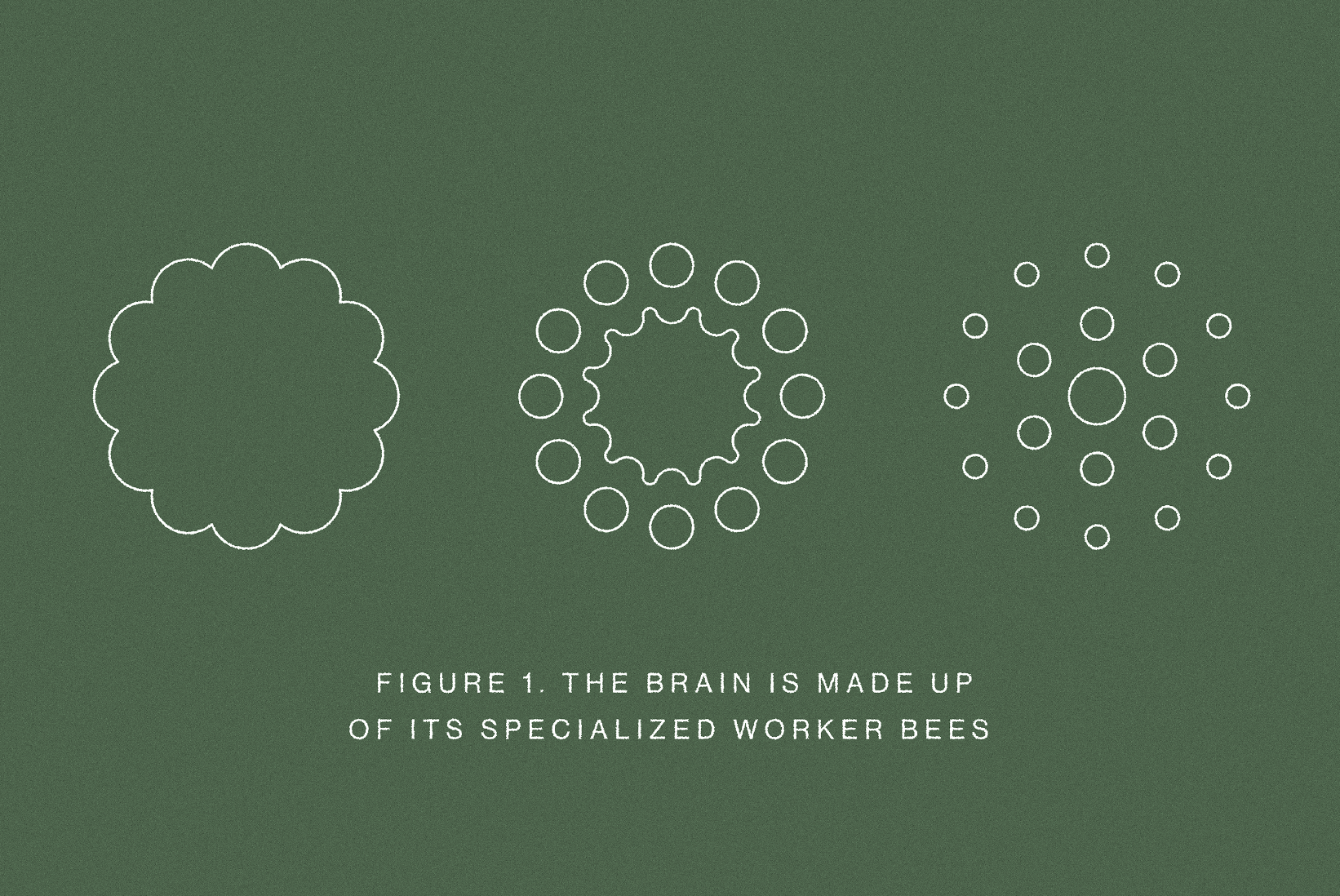

Broca’s area is a little part on the left side of your brain that controls speech production. It also happens to be one of the first regions to shut down in Dida’s rare neurodegenerative disorder, termed Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. The brain is made up of its specialized worker bees, an army of neurons. Neurons conduct the electricity that fires up an entire life – yet in all their glory, they cannot divide or make more copies of themselves. So, when it begins to die, the bulb dims away.

Most neurological disorders manifest with a variety of symptoms and each patient finds themselves writing their own story. Dida slowly lost the ability to speak more and more words, which is when I came face to face with poetry. I decided to peek into that parallel universe of Dida’s neurodegeneration. Tishani Doshi, an Indian poet from Madras, describes hope as both “a booby trap” and “a noose around [her] neck” in her writing. It turns out that Dida and I could take this meaning and turn it around from one into another, and the result would be a strange tour of a poet trying to grab wisps of their best friend, and a scientist wondering whether two brains can remain in silent conversation. Their colliding landscape began to pave our way ahead.

The machinery that runs our memories has intrigued us for decades, and the arts have had a fascinating impact on understanding the brain. In the book, Secrets of Creativity: What Neuroscience, the Arts, and our Minds Reveal, Suzette Henke coins the term ‘scriptotherapy’ to describe how writing is necessary for healing. Writing was vital to the lives of Virginia Woolf, who suffered from depression, and D.H. Lawrence in his struggle with anxiety. It was crucial for James Joyce as well, who dealt with symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Writing in this context captures the transfer between experience and fiction. Even today, such processes bear relevance for caregivers and patients alike, as though they were a bridge of clouds across the horizons of Dida’s mind and mine. It meant stepping back from the embers, finally sent to burn elsewhere.

Let me now draw your attention towards a little part of your brain that has stood the test of evolutionary time: the amygdala. This bi-lobed structure sits in its deep cushions and regulates our mood, emotions, and fear-processing, amongst other things. Interestingly, brain research explained by Daniel Schacter and Bessel van der Kolk has suggested that during the creative process, retrieval of emotional memories may occur from here, as opposed to the main memory-storing areas of the hippocampus. Patients with post-traumatic stress disorder have also been shown to have decreased activation in Broca’s area, which could indicate the lowered ability to use spoken communication to process these incidents.

Writers like Woolf were then simply re-enacting their emotional baggage through a medium where their characters could reclaim the author’s personal selves. Viewing creativity as their only saviour, they reconnected these memories and high-powered emotions into a life that was not their own. In many ways, I ended up doing something similar: to remain a spectator and be finished with the story when the pages closed. But for me, the story also carries an interrogation of the brain and the Orwellian state it was constructing inside Dida. Where did its authority begin and how far along have we managed to slip through the cracks?

In a unique study, poetry workshops conducted among early-stage dementia patients revealed that participants use this mode of expression to supplement their self-esteem and personal growth while dealing with progressive stages. Poetry works in both ways: it not only functions in creative interventions for patients with disorders but also serves as an arena for their caregivers and family members. I will not digress towards the philosophical implications that poetry might hold for understanding the brain but will leave you to think about the multitude of possibilities that can be explored in this manner, which standard tests and practices do not permit. Expressive writing is known to be immensely helpful in processing emotional imbalances, but I realised that a scientist could never fully do justice to explaining the process. When the artist William Utermohlen was diagnosed with probable Alzheimer’s disease in 1995, he began using his art to document the changes in his mind. His self-portraits over the next five years display a decline in visual and motor skills, and their rapidity is juxtaposed against his own efforts to understand his declining mind. Dida was a wonderful painter and chef, among the many other talents of her old self. And in our poems, the person before me and the lady who raised me are two entirely new people living with the same mind.

I try to use art to see changes in her brain, but only from a retrospective lens. Research has investigated whether we can do so from a predictive angle, but it is quite a bold suggestion and is still being questioned due to its subjectivity. Nevertheless, it is interesting that a study found some systematic evidence linking neurodegeneration and visual art-making. Patients with different neurodegenerative disorders have been shown to display specific changes in their artistic abilities, such as symbolism, emotional expressivity, and abstraction. Alzheimer’s patient-artists showed an increase in abstraction, supposedly due to specific spatial impairments of perspective and depth, which correlate to damage in specific areas of the brain, including the area governing memory.

As easy as it may be for the scientist in me to pore over the brain’s regional variations and all the signals pinging off its towers, communicating with one another, talking to Dida and trying to interpret every minuscule change in her facial expressions have taught me better. The narration between us, the journey to find out what goes on behind those closed curtains, and the desperate hope for it to stop unspooling in Dida are not things that a dying group of cells can explain. In fact, explaining this rare disorder to her enormous social groups and familial circles would prove easier when interspersed with tangible creations and visual images.

The lack of awareness of what the brain really does leaves most of us in the unknown. We might question the replaceability of the brain in all our science, but we inevitably bow to creative forces to make it more relatable to the people around us. Even as you read this, the neurons that talk to each other, telling you what to think and do, are not the ones in me. The past two years saw me travel through time with Dida and wonder whether the mechanisms I attempt to study each day are playing a chess match of their own. Perhaps this powerhouse is so constructed to only reveal its true self when we are ready to hide amidst its machinations, its pink tendrils and ridges winding their way towards an embrace.

Words by Spatika Jayaram.

Art by Dowon Jung.