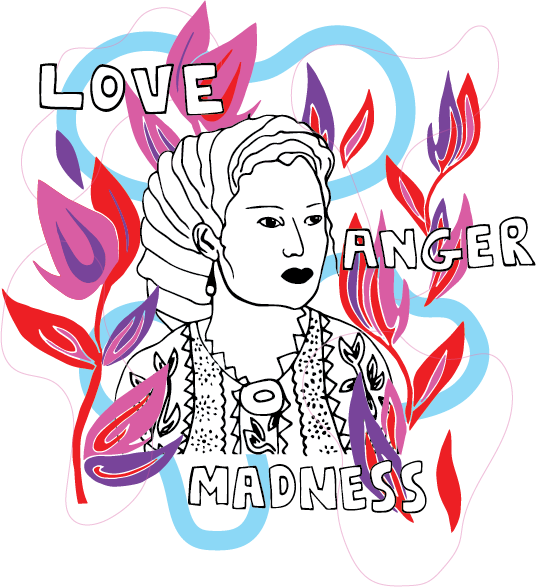

Love, Anger, Madness: Rebellious Haitian Literature almost Pushed off the Edge of History

CW: Sexual Assault

After the suspicious death of three family members, Marie Vieux-Chauvet and her family halted the production of Love, Anger, Madness. They travelled across Haiti to destroy all published copies, and she left her underground literary society The Spiders of the Night in order to flee to New York. She would die there before she could return home or publish again. This book held within it a power that threatened her life – a threat that came from a figure embodying prejudice of the most extreme kind.

Haiti had powerful enemies. Born in 1804 out of the first successful slave revolt, it was the first independent black republic in the Western Hemisphere. After releasing itself from the torturous grip of French slavery, the formidable former coloniser enforced reparations over the state for 122 years. A sickening $30bn worth of reparations was paid to the slave owners who ‘lost’ their plantations. Equally, the US had motives to prove that an independent black nation would never work – eventually moving to invade the country for economic advantage. The US’s greed would lead them to become the largest economic supporter of one of the most aggressive dictatorships in history – a financier of Marie Vieux-Chauvet’s hell.

This unending history of oppression left scars that manifested themselves in many corrupt Haitian leaders. But in 1957, one ruler, fuelled by a lethal god-complex, pushed the boundaries of tyranny to new heights. Francois Duvalier altered the Lord’s Prayer recited in schools, replacing all references to God with his pseudonym: “Papa Doc”. Claude Moise noted that the Duvalier Dynasty “innovated repression to a level of brutality and perfection never before seen.”

“Our Doc, who art in the National Palace for life, hallowed be Thy name…”

Under Duvalier’s shadow, countless artists and activists faced repression of the most extreme kind, such as the revered feminist speaker, Yvonne Hakim Rimple. She was dragged away from her home as her daughters were viciously beaten by masked soldiers. She was found the next day in a ditch, naked and likely raped. She would never speak publicly again.

Among countless other cases, despicable suppressions of freedom forced Marie Vieux-Chauvet’s masterpiece into the margins of history, until a copy was recovered and published in 2005. Vieux-Chauvet’s unfortunate reality should not only elucidate the power of the disgusting Duvalier Dictatorship but also reveal the counteractive power of art and literature – a threat able to scare even that self-proclaimed “immaterial being”. There is no better description of Duvalier’s Haiti that I can give, other than the life and art of Marie Vieux-Chauvet.

Love, Anger, Madness is composed of three novellas – titled accordingly – which relate to each other only in their context and themes. Vieux-Chauvet captures the many experiences of Haiti under the Duvaliers by using a melange of varied styles from play-script to poetry. She simultaneously leads us through a gallery of Haitian literature and the eclectic culture of Haiti. She guides us through the hierarchical racism that Haiti inherited from French colonisation to the spirits of Vodou brought from its African heritage. At the time of writing, this deep history had led Haiti into the haunting setting of our novel: a nation horrendously abused by an untouchable despotic god. But the unseen antagonist of Vieux-Chauvet’s fiction was not plucked from imagination. He transcended the pages of the novel and loomed over her household. And in response to that damning weight, Vieux-Chauvet transcribed her world into a vitally uncompromising exposé of the most brutal and intimate kind.

Vieux-Chauvet sketches the horror before her by dissecting three distinct parts of herself, one in each story, that have been violated by the Duvaliers: her freedom as a woman, as an activist, and as an artist.

“I am nothing but a heap of mutilated flesh.” ~ Love

In Love, Vieux-Chauvet introduces her personal freedom – fittingly in the form of an intimate diary. Under the repression of two tyrannical ‘male’ figures (the French and her own government), the invasion of the protagonist’s bodily autonomy serves as a haunting metaphor for the abuse of Haiti itself and a guide to resistance. The diary is quietly infuriated. The whole novella wants to scream with frustration. It explores the forces that were tearing Haiti apart through Claire’s relationship with two dominating male characters.

Firstly, she indulges in a poisonous lust for her sister’s aristocratic French husband (Jean-Luze). His presence spotlights Claire’s position in society as less valuable on account of her darker skin. This is a position she shares with her author. Taking Claire’s body (and by proxy Vieux-Chauvet’s) as a stand-in for the island of Haiti, her internalised self-deprecation is reflective of the country’s inwardly directed discrimination. Race-based classism is inherited from its French colonisers, plaguing the nation with decades of social disharmony.

Francois Duvalier was supposed to lead somewhat of a countermovement against this inherited infighting. He campaigned as a good-hearted doctor and became a figurehead for the marginalised black majority. He represented a movement to give a voice to the silenced. Echoing this, when a new Police Captain is sent to Claire’s small town he brings a prejudice toward the French-modelled aristocratic upper class. Like the Duvaliers, this is expressed as unthinkable violence. The commandant’s particular cruelty towards women is an important quality he shares with the Duvalier regime. He targets women who refuse to submit sexually to him – looming ever closer to Claire, who never relents. This is a metaphor for Vieux-Chauvet’s role as an undying rebel in the face of Papa Doc’s violent suppression, perhaps a plea to all Haitians to retain autonomy from this evil movement. Vieux-Chauvet is clear to punctuate the narrative with a theme that permeates the entire book: personal oppression can only lead to revolt.

“I saw his horrible hand approach my body and touch it ever so lightly with a kind of unbearable, sick curiosity.” ~ Anger

Anger begins with a sudden jolt. With no explanation, no names, no faces, a family’s traditional home is bordered and seized, leaving them stranded in their own country. This incredibly Kafkaesque set-up leads to the most forthright description of the Duvalier system in the trilogy. It is a document of many political abuses. Despite a false sense of freedom within their walls, the family is flooded with dizzying legislature, fake signatures, coercion and slow bureaucracy that leads nowhere. We are clued into the real experience of those deemed unworthy of rights, their voices systematically eroded to nothing. The family is a study of life in the margins of politics.

In each chapter, we closely watch the hopeless struggle of the seven family members with overlapping chronology, yet all intertwining and with a trajectory to coalesce. We see drunken escapism in the mother’s story, attempts to manipulate the system in the father’s, but submission in the daughter’s, whose nauseating sexual abuse is central to the unbearable frustration. Vieux-Chauvet reminds us, with almost unreadably intimate detail, of how the Duvaliers tightened their constricting grip on the population by using sex as a “currency of power”, in Laurant Dubois’ words. The Duvaliers and their militia (the Tonton Macoute) discovered that committing the most traumatic and scarring atrocities was the best way to stifle the voices of women, along with anyone who cared about them – just as they did with Yvonne Hakim Rimple. Anger bubbles out of the pages and fills the reader’s mouth with a shaking need to do something, yet we are left stuck in the same futility as the rest of the family – forced to do nothing.

But, just like Claire in Love, glimmers of resistance flash out of the dark. In the narrative with the grandfather and disabled child, Vieux-Chauvet gives us this image of an older generation telling stories of ancestry, a deep history of slaves freeing themselves from the plantation, the very ghosts buried in the land they defend. In a novella clearly addressing modern politics, Vieux-Chauvet subtly reanimates imagery of Toussaint Louverture, Boukman, Dessalines and countless Haitian revolutionaries freeing themselves from French slavery. It is perhaps not just a memory, but a threat to the Duvaliers that, when they re-enslave the political system, Haiti’s history is fated to repeat itself.

“Maybe it is just the screaming silence that the human ear can make out only when everything is quiet.” ~ Madness

In the abandoned house where we find Madness, a handful of destitute, censored poets cower after their friend was shot by soldiers and left on the porch to rot. Vieux-Chauvet brings us to a third part of herself that has been attacked by the Duvalier Dynasty: herself as an artist. The image of a dear friend’s corpse melting in the hot sun, and a poet deliriously writing inside – drunk, hallucinating and starving to death – is extremely close to Vieux-Chauvet’s real grief. She wrote this by locking herself in her house for six months, producing a story that attempts to drag us into her desperate delirium.

Madness, in many respects, is literature with blurred reality. The poets see their own writing come to life as they witness psychedelic displays of demons and glorious uprisings appear through the peephole. Meanwhile, the medium itself shape-shifts through prose, poetry, and eventually theatre script. In both the characters’ lives and Vieux-Chauvet’s, the line between their art and reality is vague. This punctuates the triptych with the disturbing reminder that what is written here is not just fiction. Intertwining life with literature serves to not only actualise the almost unrealistic degree of suffering, but also to inspire an urgent cause. Even the half-dead artists, with nothing to give or lose, must eventually leave that house of madness and lash out with desperate passion.

Perhaps she is beckoning other censored Haitian artists to come out of hiding, or maybe she is inscribing her own obituary, writing these poet-rebels to the execution block. Either way, the final message is clear: to have a voice is worth any cost.

“Oh Christ. Since they are going to tie us up to a post like they nailed you to the cross […] let our deaths mean something.”

In 1984, 16 years after the release of Love, Anger, Madness, the Duvaliers broadcasted a luxurious ball on national television, ironically, as a benefit to raise money for the poor. But the $30,000 necklace, expensive champagne, and tailored suits clashed with the extreme poverty of the people watching. The subsequent uprising against Jean-Claude Duvalier ended with the Tonton Macoute beating a pregnant woman to death in the streets. Vieux-Chauvet’s horrific account was stepping onto the public stage. The people, their politics, and their freedom of expression had been violated too far. And, true to life imitating art, two more years of revolt would finally lead to the exile of the Duvaliers – an uprising powerful enough to kill gods.

The public took to the streets for their personal freedom, as a powerful political force, and with a revitalised movement of activists, intellectuals, and journalists. In this crucial book, Vieux-Chauvet dissected herself in three portions: a woman, a political force, and an artist. After her death, the trinity of her spirit would return to embody the revolution. ∎

Words by Kristian Suszczenia. Art by Taya Neilson.