Review: The Golden Cockerel

A trumpet blares – tremolo builds, anticipation hovers. The mesh background drips starlight as the orchestra drifts downward in a minor key. A soldier glares at the audience, and I find myself in an enchanted world somewhat reminiscent of our own.

An astrologer takes the stage. There is a deceptive simplicity to this opening scene of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s satirical opera, The Golden Cockerel. Though the astrologer describes the ensuing story as “a moral tale for good folk” and “an old fairytale come to life,” the plot that follows is anything but crystal-clear – a strangeness captured charmingly in the recent performance by Oxford’s Orchestra VOX.

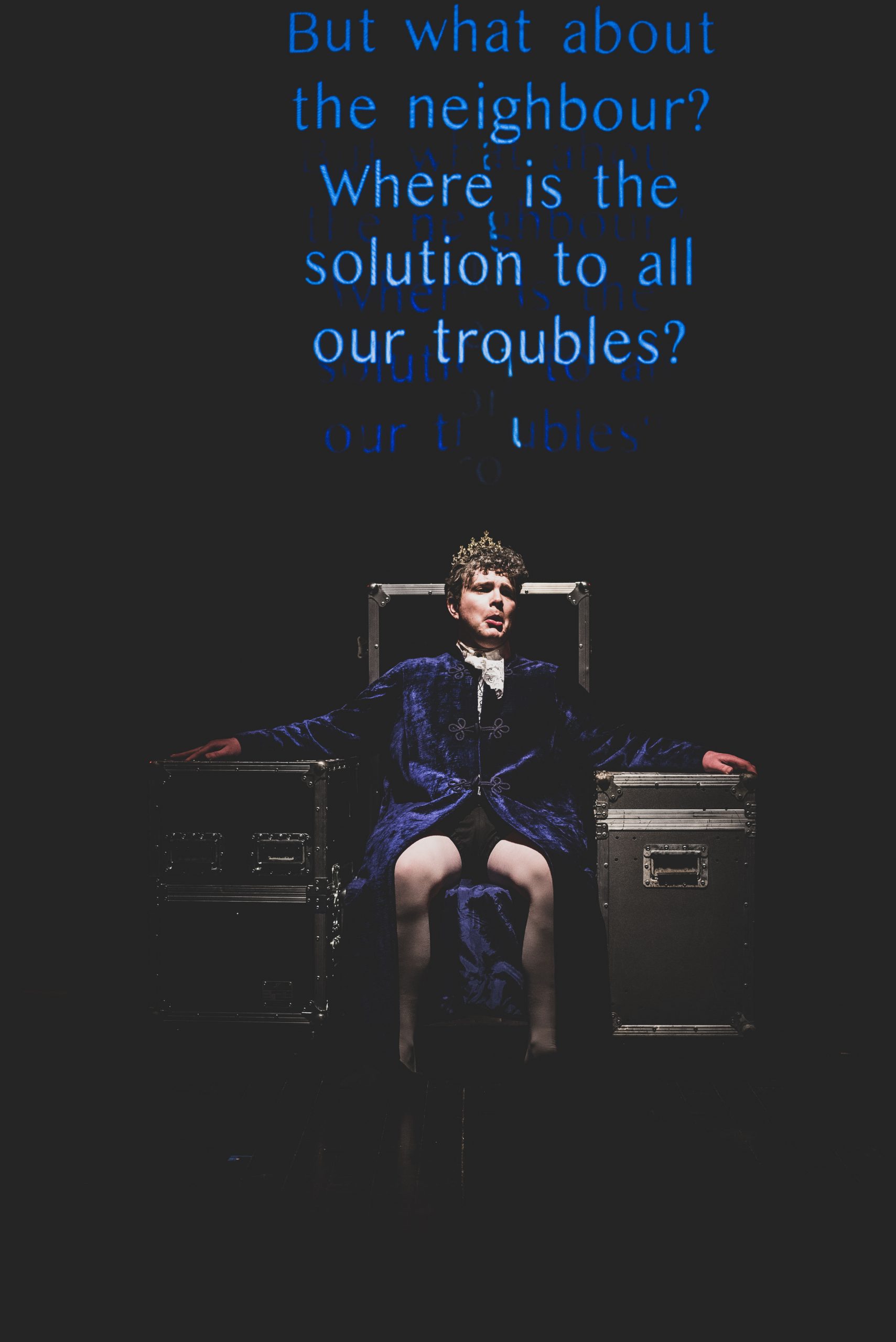

The story centres around the lazy and incompetent Tsar Dodon, a paranoid leader who feels that war is imminent. He and his two similarly incompetent children – one armed with a belt of soda cans, the other with a toy sword – flop back and forth between strategies, all half-baked. Any fancy from Dodon immediately becomes unquestionable – “How simply the matter is resolved!” The astrologer then takes the stage with a proposition for Dodon: he will provide him with a golden cockerel to warn him when danger is imminent, allowing him to nap in the meantime. In exchange, Dodon promises to fulfill any one request from the astrologer.

After a stretch of alternating naps and false alarms, Dodon is alerted – the time for war, the cockerel tells him, has come. He sends both his sons to battle before heading to war himself. He eventually discovers them dead, but hardly a moment later the grief dissipates: He sees before him the beautiful Tsaritsa of Shemakha. Through most of the act, she seduces him with food, drink, and song, and she is ultimately brought back to the kingdom as the companion of an enchanted Dodon.

Yet there are no happy endings for our ageing tsar. The astrologer returns having decided his wish: he would like the tsaritsa. Dodon refuses. He goes so far as to attempt to kill the sorcerer (“Here’s how I argue,” he says as he strangles him) but fails, and the golden cockerel pecks him to death. Our absurd tale thus ends on a reasonably absurd note, framed by a speech from the astrologer that serves as an even more absurd epilogue: “Only the tsaritsa and I were real,” he reveals. The rest of the characters had all been mirages, and us audience members need not worry about the bloodshed. The opera concludes.

In today’s context, The Golden Cockerel straddles a tense boundary. Its content is anti-autocracy and anti-war. Through the story’s often ridiculous plot, these themes continually shine through. Yet in form, it remains the case that the opera was written by Rimsky-Korsakov and inspired by a Pushkin tale. The Golden Cockerel is thoroughly grounded in the cultural lineage of Russia – a country whose past and present drips with the very same imperialism this opera seeks to resist.

During the past year of renewed fighting in Ukraine, Russian culture has often become a target of criticism from those who seek to show solidarity with Ukraine and its people. For this reason, perhaps, posters for Orchestra VOX’s performance were allegedly “ripped off the boards across Oxford,” an intern at Orchestra VOX tells us, “while the posters around them remained intact.” Is this response appropriate?

This sort of question might itself be misplaced. To focus the discussion too heavily on specific pieces of Russian culture – for instance, whether their specific themes or origins justify their being performed today – may itself obscure the structural inequalities which lurk behind the history of Russian art. The question of “Why do we know Rimsky-Korsakov’s name in the first place?” deserves its own thought, and the answers to that question reveal that the matter is not so simple as testing the value of specific works of art.

Yet it remains interesting to consider the extent to which The Golden Cockerel is – and has perhaps always been – an anti-authoritarian project. The history of Russia in its relationship to Ukraine is emphatically one of imperial domination. In parallel, the history of The Golden Cockerel is one of resistance to unjust leadership. Pushkin’s original tale of the bumbling Tsar Dodon was written in 1834, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera was completed in 1907 and first performed in 1909, a censorship-driven delay that made the premier a posthumous one for Rimsky-Korsakov. Orchestra VOX’s performance captures and extends this history of anti-tsarism, bringing this old satire of imperial autocracy into a manifestly modern form.

Anachronisms pervade Orchestra VOX’s opera: a can of baked beans stands on the same stage as the astrologer’s ornate robe. Speaking with Archie Inns, who played the elder (“impetuous, drunk”) tsarevich, I learned more about how the group’s “collection of props spanned [centuries], all the way back to when it was composed in the 20th century, right up to the golden cockerel’s t-shirt,” which bore Lenin’s face photoshopped onto a KFC logo. Some of these references are perhaps erratic in their target – Soviet iconography takes the stage more directly than allusions to the present war in Ukraine, lending some less-than-ideal obscurity to the exact point the performances seek to make. But admittedly, amidst 21st-century props and often palpably ironic deliveries, it would be ungenerous to claim that a relevance to contemporary Russia did not seem to be considered implicit. A broad, if at times vague, commitment against authoritarian leadership therefore seems to underscore Orchestra VOX’s choices. A similar notion is explored by Inns: “The problems and the moral – that is, the most central parts of the story,” Inns shares, “fundamentally speak of much larger universal truths.” Orchestra VOX’s performance wants to be more than just a rehashing of Rimsky-Korsakov’s early-20th-century criticisms. It pulls this censure into the present, using props and sets from across time to drive home the point that resistance to injustice should be universal.

Thus, when audiences catch on to the glimmers of profound relevance that so often pop up throughout the opera, this relevance is reinforced by Orchestra VOX’s unique production choices. When Dodon rants – “The law? How absurd. I’ve never heard about it. My every whim […] is the law!” – his words are chillingly current. When the battlefield is described as “the ghost of an empty wasteland,” or when audiences are told that “only crows guard the heaps of the dead,” one is reminded that the horrors of war extend across centuries. And when the Tsarista of Shemakha sings “mortal man, seize every moment, give every hour to love,” her counsel resonates.

There is an unmistakable timelessness to Rimsky-Korsakov’s satire that Orchestra VOX’s performance captures. But one must remember that the real world is far less simple than Pushkin’s tale, as absurd as that tale is. There is no astrologer to enter the stage and hold autocrats who “burden the world without consequence” to their promises; there are no cockerels to peck the villains to death. The Tsar Dodons of the real world are rarely so bumbling as their fictional counterparts, and they are certainly not mirages. Their victims are by no means audience members who need not worry about bloodshed.The Golden Cockerel is thus a useful tale with a valuable message, and though that is a good place to start, it is only a start. Hopefully, morals like those in The Golden Cockerel will manifest themselves in action against autocracy and imperialism in the future to come. ∎

The Golden Cockerel, an opera by Rimsky-Korsakov, was showing at the Garden Quad Auditorium in St John’s College from 26-29 January, 2023.

Words by Wyatt Radzin.