Review: Six Degrees of Separation

“I read somewhere that everybody on this planet is separated by only six other people,” Ouisa Kittredge tells us in a roll-credits monologue towards the end of Six Degrees of Separation. “Six degrees of separation… I find that A) tremendously comforting that we’re so close and B) like Chinese water torture that we’re so close.” John Guare’s hit 1990 play, staged for St John’s Arts Week, brings characters into orbit who, with no previous relation to each other, can change each other’s lives. Worlds apart, they are all suddenly incredibly close. But in Guare’s world of high-class phonies and liars, closeness is trickier than it seems.

Six Degrees of Separation is a self-conscious choice for a college arts week: it’s all about how we relate to art, or rather how we pretend to use art to relate to other people. Taking a plush seat in the lavish St John’s Garden Quad Auditorium, we are greeted with a very attractive set. A living room in 90s Manhattan, a Kandinsky on an easel downstage left. The painting is interpreted for us time and again, but the meaning is self-evident: the painting is double-sided, so its owners can look at it but show it off as well. A piano, a drinks table, eclectic bookshelves: its owners want to impress their visitors, and the audience is suitably impressed. The same goes for the costumes: Ouisa’s black evening gown and white gloves, Kitty’s silken red top and fur jacket. It’s all a façade – we are left in no doubt about it – but it’s just so enjoyable. And that’s the problem.

The art dealer Flan Kittredge and his wife Louisa – though she goes by Ouisa, darling – are a wheeler-dealer social-climber double act, jointly narrating the story of their terrible fright. Trying to impress a rich client into buying a Cézanne, they are interrupted by a wounded young black man, Paul, apparently a schoolfriend of their children and the son of Sidney Poitier. Enthralled by his celebrity and charm, they invite him over for the night, only to catch Paul having sex with a violent hustler and then fleeing the scene. Here begins an unlikely intertwinement between a rich New York couple and a desperate conman, who gets back in touch with them after his next dupe commits suicide. Despite betraying the Kittredges and even claiming that Flan is his father, thus legally implicating him, Paul still manages to win over Ouisa, who offers her help. In this she fails. Paul is arrested and later, we are led to believe, kills himself in prison. But he has shaken the lives of those he has seduced forever.

The reveal, of course, is that the Kittredges are conmen too. Marni Wilfred’s charming, enigmatic Paul, appealing to the end, is not much more suspect than Cosimo Asvisio’s sleazy, art dealing Flan. A cast entirely of phonies, all desperately performing status to each other, risks being headache-inducing. But Annabelle McInroy’s moving performance of Ouisa turns high-society egotism into haunting desperation. Why does she tell Paul, a conman she has only met once, that she loves him when he calls asking for more favours? Because “he wants to be us!’” Validation of her lifestyle, which the caricatured millennial youth despise, is all she asks for. There is a refreshing sincerity in this lunacy, matched only by Sol Woodroffe’s stand-out turn as the naive Rick, recounting his dizzying, terrifying night out on the town with Paul, which had the audience in stitches before the tragic twist.

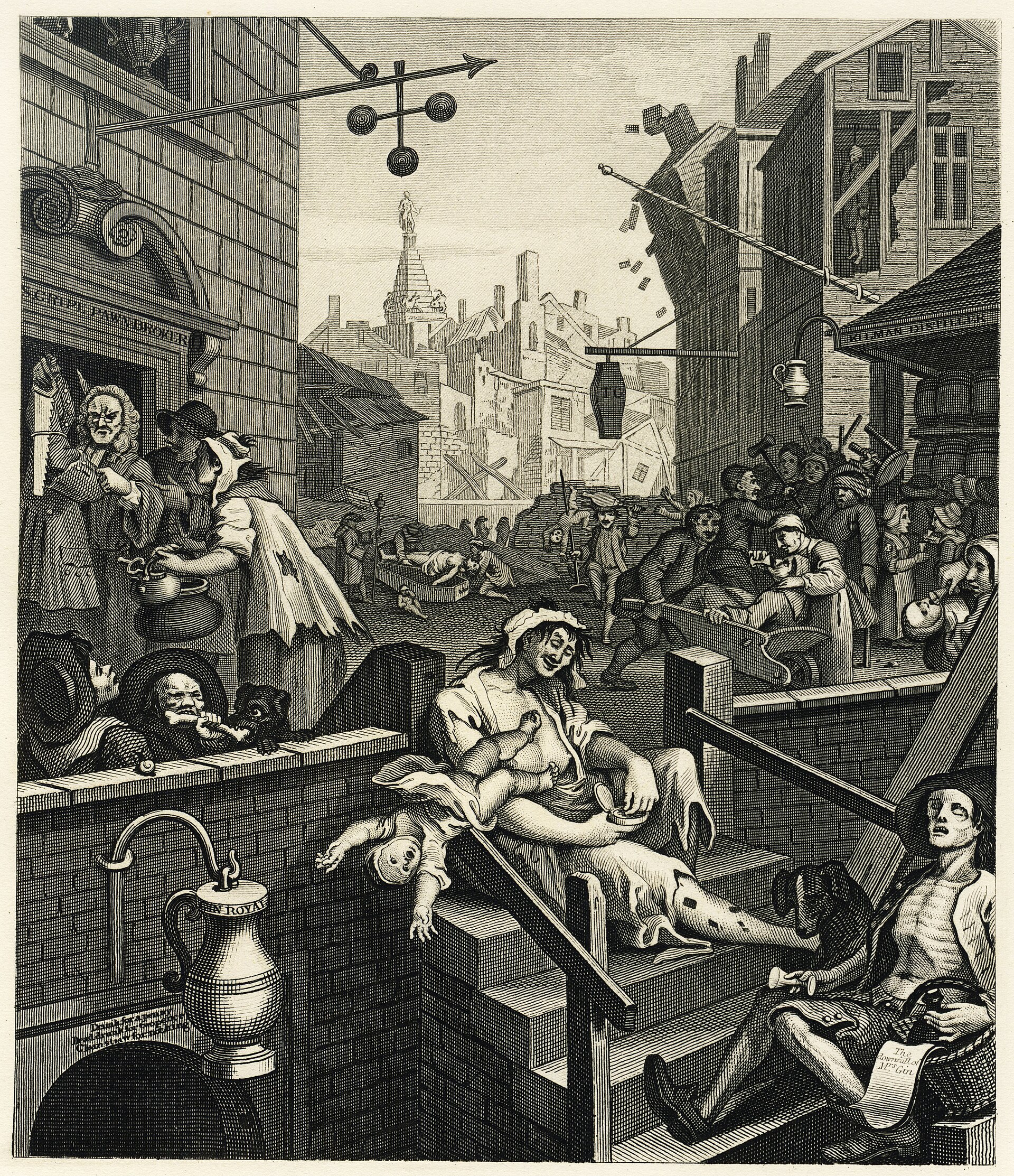

This is a play about status anxiety. It’s about performing what Pierre Bourdieu calls “cultural capital,” where the Kandinsky in your living room is a sign of social and economic status: you have the money to buy it, and you have the taste to appreciate it, and you have the education to speak about it. The Kittredges wax lyrical about Cézanne’s apples and Renaissance Florence to their rich visitor. Then, under a blue light, they face the audience in Kardashian-esque confessionals: “two million dollars,” “the figure is superfluous,” “I hate it when you say superfluous.” Anxiously correcting each other’s social behaviours – talking about money, using the wrong word – their sheer aspiration is their driving force. This is the rotten home, the rotten society, where an equally aspirant conman can work his magic. Even Central Park is represented by the same living room with a few trees and green lighting: the same rules apply everywhere.

This game is fatal, and the play frequently reminds us of that. The first ten-minutes of the play are scattered with telling references: a long speech about Holden Caulfield’s hatred of phonies in The Catcher in the Rye, Flan’s comment that “Agatha Christie would ask what do we all have in common,”and Paul’s final proclamation that the Kandinsky is painted on both sides. It feels a bit heavy-handed. We can do the working out ourselves, we promise. It’s usually more fun that way.

But these are the occasional weak points in a highly entertaining play: its 90-minute run time flies by. It is also very funny. The Cats bit comes to mind here – the musical is something the über-tasteful characters are a little thrown by, although they know they mustn’t be snobby. “You called it an all-time low in theatre,” Ouisa’s daughter pointedly says when her mother announces she will be an extra in the film. “Well, film is a different medium,” she anxiously replies. If Sidney Poitier likes it, so must she. Behind “cultural capital” lies cultural groupthink: no one can decide until everyone else has (the constant challenge of the theatre reviewer). It is in these comical moments of crisis that the degrees of separation collapse. It doesn’t matter who meets who, after all, if they all con each other or perform statuses they don’t really have. Only when the cracks inevitably show do we all become so close. ∎

Words by Clemmie Read.