Painting in Circles: the Artistic Relationships of Freud, Bacon, Andrews and Auerbach

Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach and Michael Andrews walk into a bar – it sounds like the unpromising start to a rather niche joke. It was, however, also a reality: a scene immortalised in John Deakin’s famous photograph of the four men, alongside Timothy Behrens, having lunch at Wheeler’s in Soho in 1963. This is the visual springboard for Friends and Relations: Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Michael Andrews at Gagosian’s Grosvenor Hill gallery. The image, blown up to cover an entire wall of the exhibition, shows the easy confluence of talent and inspiration. Artistic genius becomes not abstract but decidedly social and even inviting. It smokes and grins behind an open bottle of Moët and the stiff peaks of folded checked napkins. Curated by Richard Calvocoressi, the self-professed aim of the exhibition is to contextualise the works of the four painters, to unpick the complex web of relationships that fed into their art.

The list of names almost reads as a roll call for the so-called “School of London,” that loose conglomerate of artists who insisted on figurative painting in an era which gravitated towards the abstract. They moved in a tight social circle, so an acute awareness of each other’s achievements was unavoidable. Notably, Freud owned work by all three of his contemporaries and had sixteen of Auerbach’s paintings in his possession at the time of his death. It is, however, only when the work of all four figures is placed in such proximity that both the similarities and differences between them become so startling. London flickers from Freud’s Paddington Wasteground (1970-73) to Andrews’ busy Colony Room (1962) and proves almost unrecognisable under the thick streaks of paint in Auerbach’s Primrose Hill (1958). Likewise, the tender, ritualised show of paternal affection in Andrews’ Melanie and Me Swimming (1978-79) hangs opposite Freud’s famous Naked Portrait on a Red Sofa (1989-91), in which the artist’s daughter reclines, arms crossed in a stylised show of ease. The effect, as you sidle from one image to another, is like staring at a series of funhouse mirrors. The same themes emerge, refracted through the lens of each artist’s particular focus and signature style.

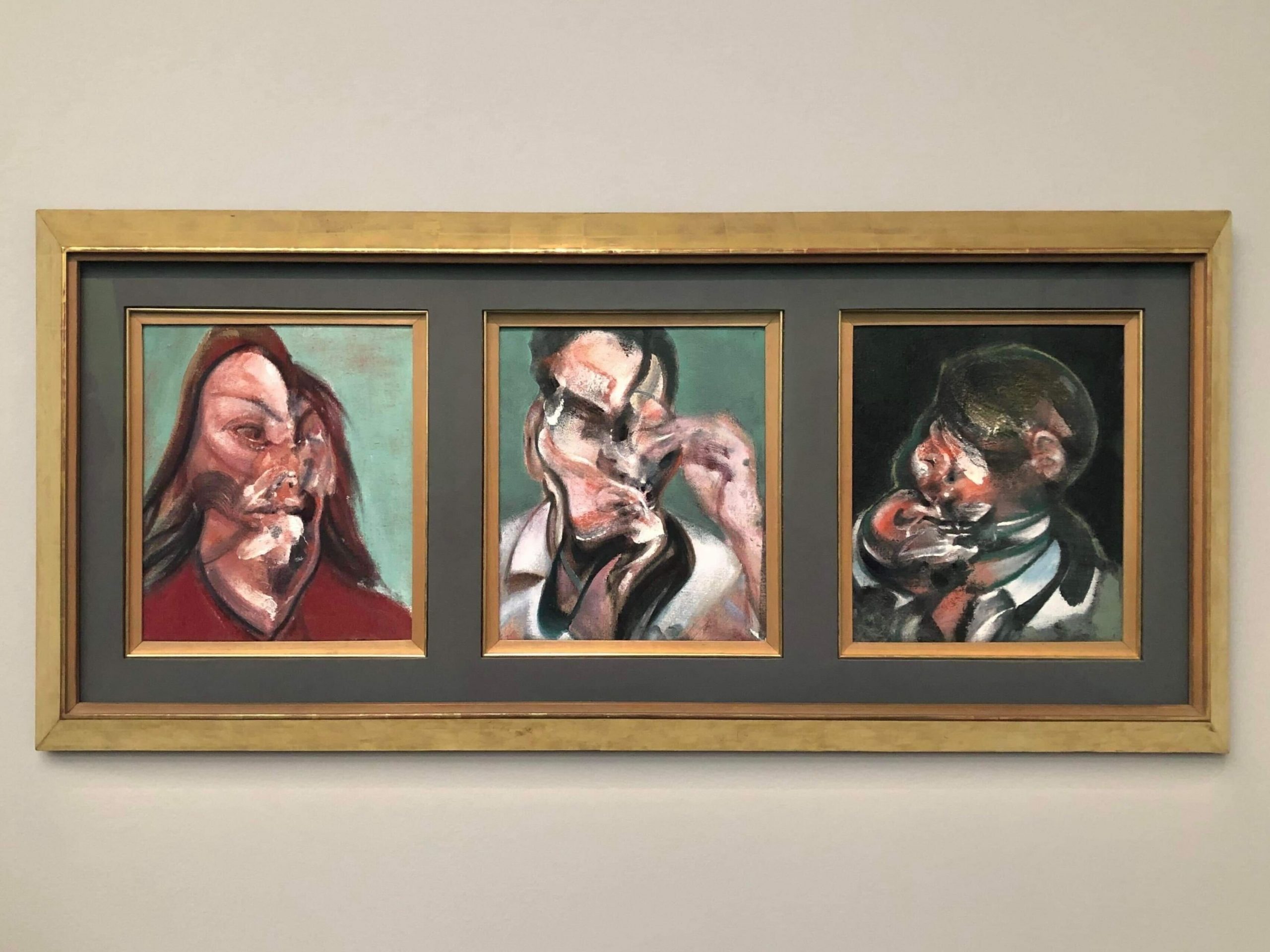

Freud remarked wryly in a 1988 Omnibus interview for his retrospective at the Hayward Gallery, that the temptation to paint oneself is perhaps due to the artist’s own “permanent availability.” The artist is the ever-present subject. But to be both muse and maker is a curiously complex dynamic. Freud’s self-portraits strive almost to defuse this charge. In Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening (Self-portrait) (1967-68), the admission of its subjectivity is pushed into parentheses even in the title. In the painting itself, Freud figures between the fronds of a houseplant, refusing to inhabit the usual solipsism of the self-portrait. Equally, in Reflection (Self-portrait) (1981-82), he meets the viewer’s eye in a steely side-glance – it is almost a reproach to the presumption of a certain intimacy between artist and audience. Freud’s instantly recognisable features are twisted and blurred in Bacon’s Three Studies for Portraits: Isabel Rawthorne, Lucian Freud and J.H (1966). As the central panel in the triptych, he is recast in that distinctly Baconian mould of devastating distortion. It matches Bacon’s own self-portrait, Head of a Man (1959): both men’s features simultaneously crystallise and collapse in colour. In short, the stability of the self is, rather paradoxically, both affirmed and negated in the portraits that litter the exhibition.

Collaboration between the artists is imposed nearly retroactively by Calvocoressi’s careful curation of the parallels between their work. Walking through the gallery allows for an odd sense of immediacy. Here are four men who moved in the same orbit, who painted the same things and often the same people. By contextualising their paintings, the boundaries between artist and art, life and work, become porous. To be an artist, then, is also to be the subject – to find parts of oneself dispersed and diffused in the work. Painting friends and relations is, however inadvertently, to paint a part of oneself and, if this exhibition is anything to go by, it is a practice that is both eternally evasive and exposing. ∎

Friends and Relations: Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Michael Andrews was on at the The Gagosian, London, 17 November to 28 January.