A Day at the Zine Fair

Several versions of Zayn Malik’s disembodied head pout at me from a pile of old Vogue copies, The Guardian’s Feast magazine, printed stills from Bend It Like Beckham, Pritt Sticks, left-handed scissors and stacks of multi-coloured paper. I pick out a particularly sulky portrait from Malik’s quiff days and glue it to some green card, besides a Nokia brick and a sunflower. Someone next to me is making a birthday card, and others softly discuss an upcoming party, but mostly the patrons of the collaging table sit in the sort of comfortable silence more common to friends than strangers.

I’m at the Blackwell Hall of the Weston Library for their Zine Fair, where local artists, collectives and activists have gathered to share and sell their work. Long used in social and political movements and in marginalised subcultures, zines can loosely be categorised as magazines produced non-professionally and self-published for a small audience. Today, people migrate in a loose circuit around the stalls, picking up stickers, leafing through the zines, and chatting with stallholders, keen to share the stories behind their publications.

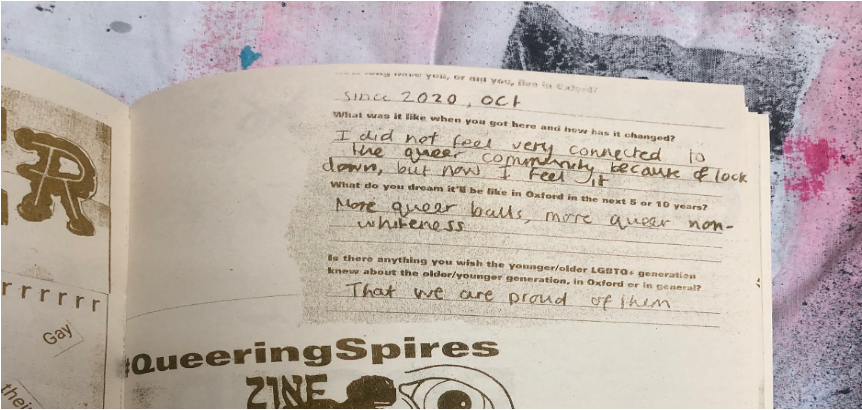

Queering Spires, a hand-bound zine made of two booklets tacked together, emerged from a partnership between queer activists and the Museum of Oxford’s temporary exhibition about hidden queer spaces in Oxford. The focus of Queering Spires is on space: the lost and latent queer geographies of Oxford (like the Royal Blenheim pub, which I find out used to be frequented by a regular LGBTQ+ clientele), eclipsed by the remaining strongholds of Plush and The Jolly Farmers. Queering Spires also shows the strong tradition of collaboration in zines. Replies to questionnaires filled in with sprawling ink discuss their relationship with Oxford’s queer community, anonymous poets long for sober queer spaces in the city, and snippets from the Oxford Gay-zette and line-drawn naked figures recline across pages. I linger over a response, which wishes the younger LGBTQ+ generation to know “that we are proud of them”:

Search for zines online, and countless images of homespun DIY paper booklets will pepper Google Images, but not all zines share this format. Maryam Rimi, a film and theatre editor from Onyx Magazine, a Black radical magazine, notes of its style that “it’s not DIY. It has a high production value. It’s about giving Black artists the dignity they deserve”. Whilst many of the other zines I flick through are consciously hand-made, Onyx doesn’t bear any signals of its own making. The pages under my fingers are glossy and weighty. Onyx’s subversive quality instead lies in its aim to bring new voices into the editorial world. “We are all about disrupting the traditional publishing sphere, dismantling it, and building something new”, Rimi says: “giving Black artists the opportunity to have their high-quality work distributed in the high-quality ways it deserves.”

Another zine with a glossy, editorial finish is Yente, a queer, Jewish student collaborative, whose editions revolve around Biblical icons, reviving and reinterpreting their stories. The members of the collective emphasise how Yente has provided the freedom to express a queer, liberal Jewish identity, which they felt was more inhibited in more formal Jewish spaces. With submissions filtering in from across the globe, the publication includes artwork, prose, poetry, and collages. Some of the pages feature pastiched screenshots of messages from The Yentes Who Raised Us, which range from the supportive and witty to eccentric emergency plans in the event of a communication breakdown. Yente playfully seizes the potential of our social media interactions and weaves it into the zine’s texture.

Along the hall from these two zines stands Adam J. Maynard, a poet who works in the stacks beneath the Weston Library. On his table are a selection of his own hand-made prints and pamphlets, as well as some he has collected. He tells me he started working here about seven years ago, moving all the books from the old site post-refurbishment. Adam creates poetry pamphlets of varying forms. Are they zines, I ask? “Poetry pamphlets is probably the term I use”. So that’s that. One of them, titled The Moon, is an A4 pamphlet stamped with an image of a full English breakfast in Riso print. Blank pages enclose one singular printed poem:

“The cold light

Of depressed chandeliers

In college dining rooms

Dim and dreaming”

(extracted from The Moon)

I ask why he made an entire book for one poem: “I suppose it’s about making something physical.” Like an artefact?: “Yes, I suppose. The means of production are cheap.”

He’s made one called A Very Brief Visual History of the Zine. On the first page, he shows me the opening line of the radical BLAST manifesto of the Vorticist movement:

“BLAST First (from politeness) ENGLAND”

It makes sense that Maynard’s Brief History begins here – indeed, some of the poetry I leaf through from his table almost feels modernist, or at least short, imagistic, moon-lit, alcoholic. But far from modernist snobbery, it’s important to Maynard that zines represent marginal voices: “It’s a form of having agency outside governmental structures and ideas of profit and capital. Spaces where certain people can exist. It’s just making, really. It’s not gonna be monitored”. He pauses to think, then adds: “it’s about things that aren’t mainstream”.

Maynard works underneath the Weston and creates artefacts of his own words as zines on the side of his main job. How did he get into working here? “I applied”, he responds. Fair enough.

The practices and ideas that permeate Oxford’s Zine Fair are not wholly new, of course. Marginalised groups have been using unorthodox methods to express themselves in print for a long time, and collage is not a distinctly modern medium. After all, zines depend on old material, both in the re-contextualising of images in collages, and the use of historic ideas and characters, such as Yente’s reappropriation of Ruth and Judith. It is energising to see institutions like the Museum of Oxford and the Weston realise the power of the medium, as the Oxford zine scene grows and gains visibility. That being said, we shouldn’t reduce zines solely to vehicles of activist commentary. Zines can function as Resistance with a capital R, with their Resistance to mechanisms of power and control by inserting hand-made textual existence as a method of retelling and reshaping narratives. But their interactivity also serves as resistance to other uses of time. At the collage table, hands fully occupied, you resist distraction, because your fingers are grubby and you need to borrow the scissors from across the table, “if you could pass them down? Cheers.”

The lightness and joy of sitting around a collage table, muddying my fingertips with Pritt Stick and stray strips of paper, reminds me how art, whatever its quality, can function as an antidote to the brutalist academic strictures of Oxford.

As I leave the fair, I slip a small sheet of card into my pocket, coated with fruits, flowers, stray objects and one-fifth of One Direction. This is no masterpiece: the images are roughly-cut and jagged, the edges already peeling upwards, the mise-en-scene haphazard and random. But it is my own little sliver of art nonetheless. ∎

Words and photographs by Julia Males and Imee Marriott.