Itadakimasu

では、ゆっくり味わいましょう。

Dewa, yukkuri ajiwaimashō, or “Well then, let’s enjoy this slowly”, I recall my grandmother saying to me over tea before watching her daily dose of travel shows. While I was living with her, the two of us would sit down every afternoon on the zabuton mats by her coffee table with freshly brewed cups of her favourite tea. She would ask me to make it with two heaped teaspoons of sugar and a fresh slice of lemon, picked from the tree she has been proudly tending for years in her small backyard. My grandmother always uses her lemons sparingly, and I know she’s filled with joy when she spots a few of those yellow fruits timidly ripening on her tree in the winter.

Ajiwau in Japanese means ‘to taste’ or ‘to relish’ something slowly: a home-cooked meal, the bitter sweetness of wagashi (Japanese confectionery), or the steaming warmth of tea. The word is reflective of the Japanese tradition of experiencing sensations mindfully. As my grandmother says, it’s about the added value of an appreciative kimochi (feeling) rather than just the taste. We use ajiwau in a less tangible way too – for a quiet walk along the coast or among rows of sakura trees, as their short-lived beauty tinges concrete cityscapes with sprinkles of the palest pink. Yet these glimpses of slower living don’t contradict the reality of a country dominated by constant busyness. Tokyo’s metro overflows with rush hour commuters and working days are infamously long. Japan’s connection to bullet trains, anime, and capsule hotels may further contribute to the stereotype of a country that is somewhat hostile to tradition. However, the seemingly incompatible habits of modernity and tradition appear to be reconciled with people’s daily lives. My country’s fondness for practices of mindful enjoyment is something I’ve encountered on my yearly visits to my grandmother’s house in Fujisawa, Kanagawa – a place where, in my memory, lively children and busy grown-ups always gather, somewhat chaotically, to share her delicious meals.

In Japan, every meal starts by saying itadakimasu. Hungry children pronounce this with enthusiasm at a dinner table, initiating a silence only interrupted by the sound of chopsticks scraping rice from the bottom of a bowl. It’s used by co-workers on their rushed lunchbreaks and by guests sat at a traditional tea ceremony. As a language student, I’m always fascinated by the cultural resonance of words and I find myself dwelling over the translation of common Japanese sayings. I like to think that it’s because the language is exceptionally suggestive, since Japanese is heavily context based. It carries the literal meaning embedded in the visual kanji but also more implicit information, which on occasion consists of references to the seasons or of ranging degrees of formality. My uncle once received an admissions letter from a university saying – somewhat ambiguously – that “the flying plum of the Dazaifu Shrine is blooming” (太宰府の飛梅咲く). Resorting to seasonal symbolism, the news came across as a very subtle and indirect congratulation. Similarly, itadakimasu expresses something different from the more easily translatable bon appetit, as the verb itadaku (頂く) means ‘to receive’ or ‘to accept’ a gift. The phrase traces back to Buddhist beliefs centred around the respect for all sacrificed forms of life, and it’s the acknowledgement of a kind offering, placing us in a position of humility.

Every meal also ends with an appreciative gochisousama. It roughly translates to “you’ve treated us so well”, in recognition of someone’s efforts in preparing a meal – it’s another example of how everyday phrases are imbued with an evocative meaning. Although I’d hear and use it all the time, only recently did I learn that the kanji of gochisousama are the symbols of ‘horse’ and ‘run’ (馳走 or chisou), creating an image of the host galloping around to take care of the guests and provide the food. With go and sama being common indicators of courtesy, gochisousama may sound unnecessarily formal. Yet it’s still used in most restaurants and households, including my own, where a conversation in English instantly switches to Japanese when thanking my mother for her cooking. Itadakimasu and gochisousama are so ingrained in our daily exchanges that failing to say them results in a nudge from a family member. Such expectations of politeness also serve to foster a widespread custom of giving and receiving (omiyage and okaeshi) that I’ve seen being perpetually reciprocated through food between my grandmother and her in-laws.

Every winter, my sister and I look forward to our aunt’s special delivery of hoshi-gaki – sweet sundried persimmons that she makes – from the south of Japan. To us, they’re the ultimate winter delicacy, and we always fight over who gets to eat more. Food, and the appreciation of it, are closely linked to 四季 (shiki or the four seasons), which are artfully featured all across Japanese culture. They are the central source of contemplation in haiku, the short and impressionistic poems composed as the poet-wanderer’s melancholic response to the changing seasons. Seasonal imagery typically forms the landscape of Edo-period (1603-1848) screen paintings, kimono fabrics, and decorative lacquerware. The seasons are also delightfully contained inside a warm bowl of gleaming shinmai (newly harvested rice), in the starchy core of satsumaimo (baked sweet potatoes) and in my grandmother’s cup of lemon tea.

Japanese cuisine always celebrates 旬 (shun or ‘peak seasonality’) in the ingredients used, making the enjoyment of food a way of being in touch with the current season through its harvest. Commercially, the seasons appear creatively packaged in limited-edition chestnut or plum flavoured Kit-Kats, which I’ve so far only found in Japan. More traditionally, seasonal ingredients can be discovered in the multi-course kaiseki-ryōri. It’s a rather fancy meal that comprises a series of small and colourful dishes representing different methods of cooking and textures. The kaiseki-ryōri is meant to enable the slow enjoyment of both balance and variety. The word kaiseki (懐石) is written as ‘bosom stone’, referring to the stone that Zen monks placed on their stomachs to keep their hunger at bay before a tea ceremony, in show of moderation. This sense of measure is still vital in Japanese cooking: the portions tend to serve just enough because, according to an old Japanese saying, in order to really enjoy a meal it’s best to be “eight-tenths full” (腹八分).

Taste is a visual experience too. Beauty and food are closely correlated ideas, so much so that the kanji of the adjective oishii ( tasty), is spelt by combining the terms ‘beautiful’ (美) and ‘flavour’ (味). Careful composition and presentation also extend to everyday cooking at home. A homemade meal usually includes the tasteful mix of white rice, miso soup, fish, and a few okazu (small side dishes) – traditionally even served for breakfast. Back home, I remember my grandmother religiously laying out the dishes herself. She would frown at us if we served ourselves rice messily, and if she noticed that the colour green was missing on the plate, she would promptly top it with some form of garnish to make the dish more beautiful. In a way, she recreates her own version of a kaiseki-ryōri on our dining table. Whenever I visit, I’m amazed by her ability to put together a diverse and nourishing meal just by using what she finds in her fridge, as well as her patience in decorating it, even if it’s just for us appetite-driven grandchildren.

Through these subtle yet expressive modes of appreciation and hospitality, Japanese culture suggests some ways in which we can savour life today, in its array of seasons and flavours. The disruptive demands of modern society often force residents in larger cities of Japan to eat alone or resort to more practical convenience store food. The pace of life and dining habits have changed, and not everyone now has the time of day to enjoy food slowly. Yet many commuters can still be spotted traveling with a beautifully packed bento box to indulge on for lunch. Eating seems to reflect the search for a more immersive comfort within the ever-changing landscape of the seasons – the same one that haiku poets crystalized into seventeen exquisite syllables. It’s a way of allowing ourselves the luxury of small, measured joys amidst a flood of appointments.

Despite Japan’s predominant sense of modernity, our daily habits, utterances, and gestures, as well as our chosen ingredients, are a gentle nod to tradition. Phrases such as osakini or ‘excuse me for going before you’, conventionally used during a tea ceremony by the guest who starts drinking, crop up in everyday interactions with colleagues and friends. Having spent a long time living abroad, I’ve grown to admire the Japanese language’s distinctive nuances and respectful intentions, imparted even to the more mundane activity of eating. With food, as with haiku poetry, words can translate the immediacy of the sensory and the temporality of the seasonal into a kimochi that lingers like the aftertaste of sweet sake. They are, I think, the unwritten recipe to a truly flavoursome meal that fulfills our feelings as much as our tastebuds. It all starts with the simple yet ever so thoughtful itadakimasu.

My grandmother recently phoned to tell me that she started baking satsumaimo on her old outdoor stove again and that she’s looking forward to my visit in December when she’ll finally be able to make them for me as well. Her words felt like a much-needed hug on a gloomy week of term, bringing back the familiarity of my childhood and the joy of anticipation that I so strongly associate with her and my native country.

Edo-period poet Matsuo Bashō wrote this haiku on a chilly autumn day during one of his solitary voyages across a mountainous and windy Japan. He evokes the homely space of a tatami room:

Smell of autumn –

Heart longs for

The four-mat room.

(秋近き心の寄るや四畳半)

aki chikaki kokoro no yoru ya yojōhan

As the colder months return my thoughts travel to similar places of comfort. They recover the warm flavours of my memory and repeat the words I was taught to use as a child. And now as I resume my hectic life as a student, I find myself craving a taste of life outside of the library. I long for home and the afternoons spent sipping tea with my grandmother.

では、いただきます。Dewa, itadakimasu. ∎

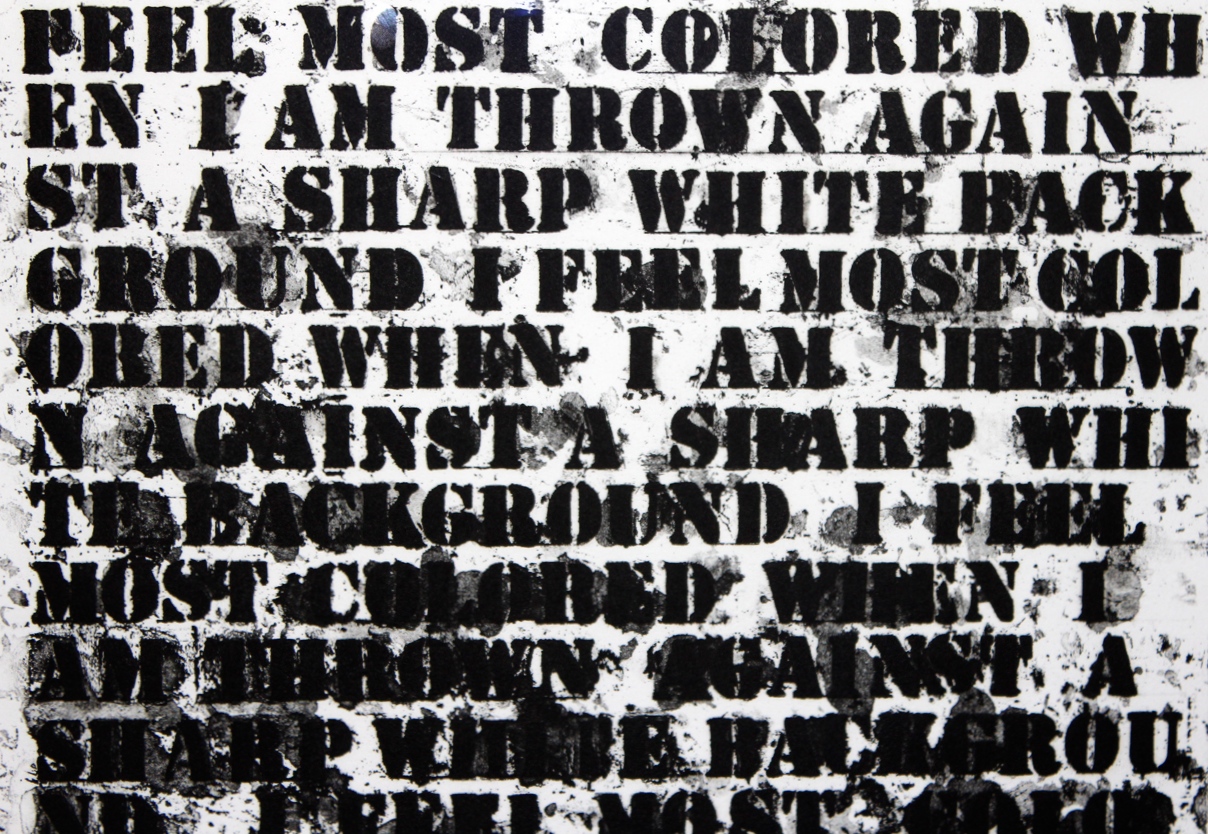

Words by Siena Muller Yamashita. Art by Elsie Gray.