Trifling

A village fete. Bunting. The air is sticky like marmalade. The scorched grass as crunchy as a brandy snap. Light up on Winnie, seventy-four, blouse the colour of stained wallpaper, standing behind a cake stall.

WINNIE: “I don’t use clotted cream.” I knew I’d have to kill her when she said that. We didn’t rub along from the start. Belinda and I. Didn’t envy her one bit, not like the others on the committee – liver-spotted sycophants – when she strutted into the village hall with her Emma Bridgewater cake tin. Skin smooth as skimmed milk. One of those bobbed haircuts that was fashionable when I was her age. Dark and glossy as a chocolate ganache, sitting on her shoulders. I wasn’t jealous of her. Not one bit. I sat there with my earl grey and garibaldi thinking what a self-pitying bunch of pensioners they were, swarming around her like that. Pathetic. And some of them only sixty!

Sniffles.

Once they’d sat down after all the excitement, adjusted hip replacements, turned hearing aids up and let blood pressures settle, I began the meeting, smoothly allocating out the savoury items (cocktail sausages, scotch eggs, cheese scones, coronation chicken, cucumber sandwiches, pork pies) like a hot knife through butter. Although we did take a vote on quiche, mind you. The cakes and traybakes have been more hotly contested in recent years, but I know how to navigate a fête meeting like the back of my Le Creuset oven mitt. Everyone knows how I run things in this parish. Cupcakes, brownies, treacle tart, lemon drizzle, carrot cake, chocolate cake and the rest were all fine to give out. Well, one or two hiccups. Mark (village alcoholic) wanted the black forest gâteau again, but I put my foot down. Not after the Jubilee fiasco when he set the gazebo on fire after flooding the trifle with Armagnac. Frightful behaviour.

Plucks tissue from sleeve. Dabs nose lightly.

There are unspoken rules to a cake stall. Every village has one. It’s like a church, but more cultish. The weighing of sugar on scales, the ritual cracking of eggs, the meniscus of vanilla extract on poised teaspoons, the pinches of salt, the incision of cake skewers, the fine mist of icing sugar, the rhythmic whipping of cream, and the licking of the spatula. It’s ceremonial. The Bake Off is my Bible. I take the sacrament of sponge and compote. I pray at the altar of Prue Leith. If baking is a religion, then I am a high priestess.

Dips finger in icing. Licks.

Now, the Victoria sponge is the most prestigious, quintessential, and sought-after cake on the stall. Two slices of sponge, the finest Cornish clotted cream and strawberry jam filling, topped with the thinnest sprinkling of icing sugar. It is the highest honour that can be bestowed on an amateur village baker, a task assigned only to the deftest tin-greaser, tenderest spatula-wielder and veteran committee member. Many people have died in the history of baking Victoria sponges. I should know. I’ve fended off my fair share of young, plump, pre-menopausal housewives (who think they know a thing or two) in my time. But she – she was something else. I’d caught her staring at me, trying to suss out my weak points, the pink corners of her mouth poised, twitching impatiently, scarlet fingernails drumming on the lid of her polka-dot tin – tap tap tap tap tap tap – echoing around the village hall rafters.

Taps table.

Until I say those holy words: “Victoria sponge.”

Tapping stops. Silence.

“I’d be happy to take that,” she says. The only noise in the room is Geoff’s faulty pace-maker ticking.

Crumples tissue in fist.

Nobody challenges my Victoria sponge. Nobody. “We normally start newcomers on the coffee and walnut,” I say. (No one likes making coffee and walnut cake.) Then she says in that treacly, sweet voice, “Oh, but it’s my speciality. In fact, I’ve brought one I baked this morning, for everyone to try.” What she does next boils my blood. More than Mr Kipling Battenburg. More than cream before jam on scones. She gets up, plies open her cake tin with those red nails and starts handing out slices of her abomination, not on paper plates, but napkins.

Starts ripping tissue.

She goes round the circle of plastic chairs, greeted with a smattering of guilty thank yous and sheepish glances in my direction. “This isn’t protocol,” I hiss. And yet she puts a napkin on my lap. There are sliced strawberries top of the sponge. A cardinal sin. Hands have been cut off for lesser abominations. The Jam? “Raspberry, Bon Maman.” Ridiculous. Nobody uses raspberry in a Victoria sponge. The filling? “It’s whipped single cream, for lightness. I don’t use clotted cream.”

Tissue shreds fall to floor.

That did it for me. I would have made an Eton mess of her head with Louise’s Zimmer frame right then and there if every pair of cataracted eyes in the room weren’t on me. They were all gawping at me, and – what’s worse – their napkins were empty, cake crumbs caught in moustaches, cream smeared into their wrinkly lips. They watched as I took a bite, probing it with my tongue. Springy, moist, rich sponge with just the perfect amount of filling. But there was something else there, scratching at my tongue. It couldn’t be. Is there lemon in this? “You noticed! Yes, a little lemon zest. My own little twist,” she said. “It’s… different,” I grumble, “but there can only be one sponge on the stall.” A dentured murmur of dissent rises. Belinda looks straight at me with an evil, knowing twinkle in her eyes. “However, this year, I might be prepared to make an exception and have two cakes on the stall. Just in case we run out.” The corners of her young, pink lips ripple into a grin. The bitch.

The peal of church bells. The tormented babbling of children. Winnie begins to cut slices of cake.

I insisted that we arrive here nice and early so I could get home and bake my sponge before the fete begins, have it nice and fresh. It’s a cake stall industry secret. It stops the cake from getting soggy, see, and the cream won’t crust over. Not that Belinda would have thought of that. She made hers last night. I could practically smell the compote rotting and whipped cream curdling from underneath her cake tin as we drove over this morning. She wouldn’t stop droning on and on about tempering dark chocolate as we unloaded the cakes onto the stall from the back of her Range Rover. We’re pitched next to the children’s games stalls at the far end of the boggy football pitches away from the village, so she kindly offered to courier the Tupperware over. We arrange the glorious spread of savoury nibbles and sweet treats over my floral tablecloth, leaving the central cake stand empty for my Victoria sponge. “I’ll just grab my cake then!” Belinda turns into the boot of her car, so I split her head open with the splat-a-rat mallet.

Eats cake.

The fête is going swimmingly and, of course, my cake stall is the centre of attention. There’s a wonderful buzz of villagers ambling around the field and – except for the hideous screaming of the brats on the merry-go-round – I’m actually rather enjoying myself. I even allowed myself a thimble of Pimm’s earlier! Wouldn’t want to shrivel up in the sun.

Winks.

“Is this raspberry jam, Winnie? That’s not like you. It’s quite pulpy,” Louise asks after sampling my Victoria sponge. The weather is delightful, a warm August breeze and clear blue skies. I smile graciously back, “Well, it’s from Belinda. A few extra ingredients this year!”, “Good for you! Talking of Belinda, I haven’t seen her yet. Do you know where she is?”

Red spotlight. Holds out slice. Grins.

Belinda? Oh. She’s here.

Blackout. Louise screams. The buzzing of flies. ∎

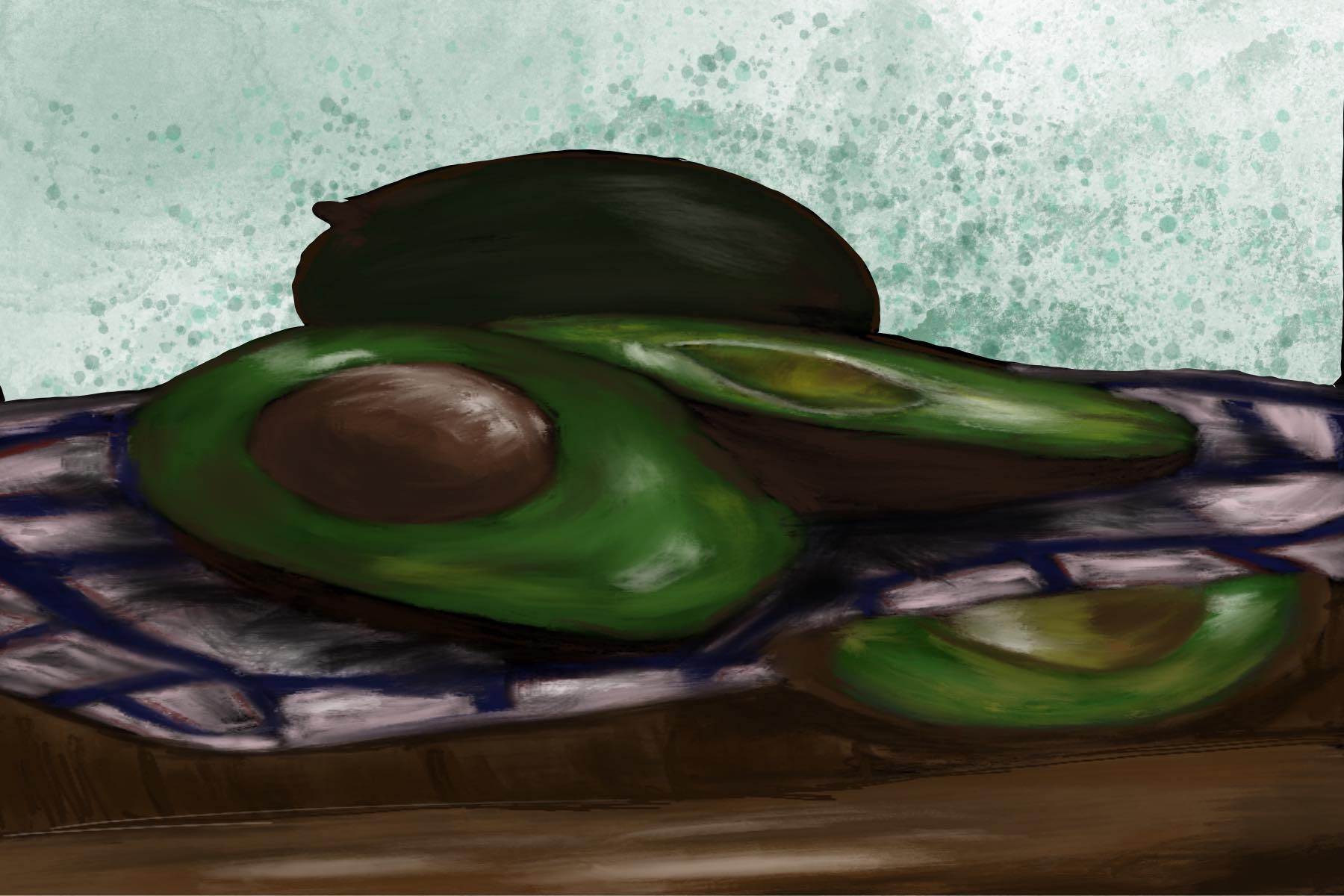

Words by Max Morgan. Art by Niamh McBratney.