On Asphalt and Satin

Sei allem Abschied voran, als wäre er hinter

dir, wie der Winter, der eben geht.

Be ahead of every leave-taking as if it were behind

you, like the just-departing winter.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Sonnets to Orpheus II, XIII

I live in Berlin and study in Oxford. Every time I come back to Oxford, it is a sojourn from the everyday and an immersion in another world. In some ways, they seem like vastly different cities. There is hardly a building older than the eighteenth century in Berlin, and hardly a building newer than the eighteenth century in the centre of Oxford. But distinct as they may be, daily life propels me through the two cities in similar ways. And as I walk, I see.

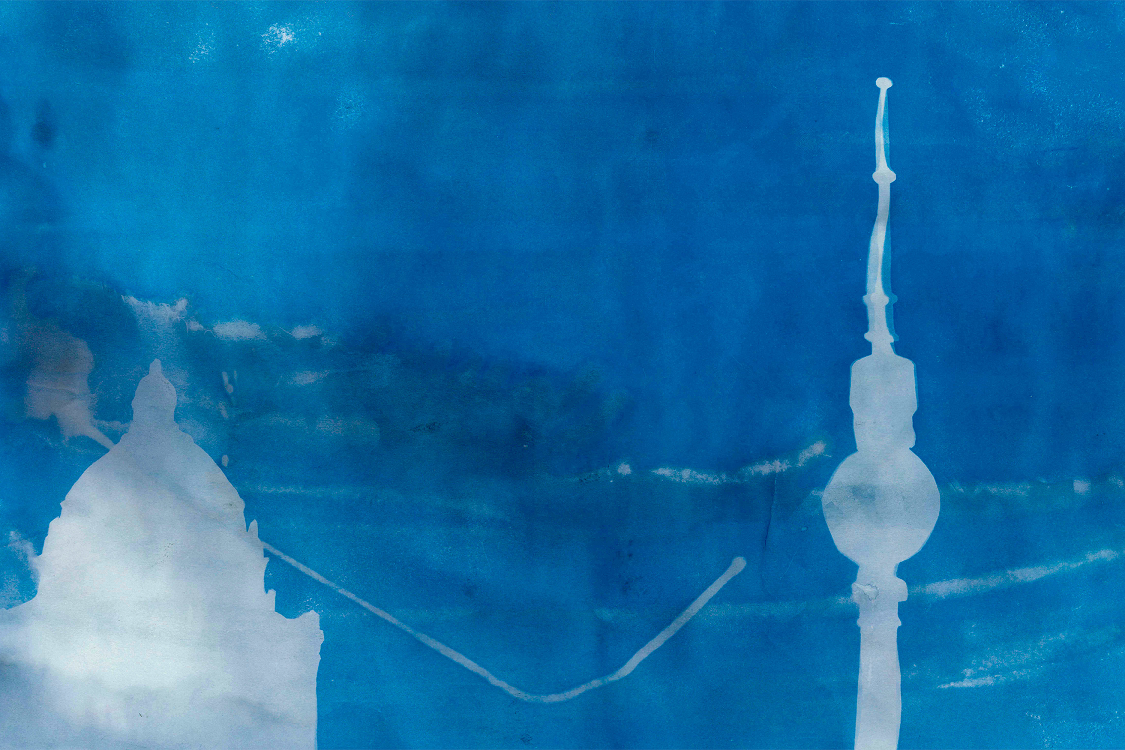

The German capital, riven by history, is as reliably dubbed ugly as Oxford’s spires are extolled as exquisite. Berlin’s blue sky is cut in two by the TV Tower twinkling invitingly (or menacingly) where avenues terminate. But attention turns an eyesore into a thing of beauty. Gaze at the concrete stem of the construction shaded by sunlight: the blank surface is wholly unornamented, yet shadows shape a form that can capture the eye. And while the mirrored globe might first attract viewers with jaunty retrofuturism, its glass and metal pyramids are also a sight worthy of reverie. In some ways, the looming Palladian weight of the Radcliffe Camera protruding above Brasenose College’s squat cloisters is no less alien, no more beautiful.

Indeed, Headington limestone and pre-Wende steel both catch the sun in alluring ways. I was taught that beauty resides in the Sheldonian’s harmonious façade, and amidst the pristine, remote landscapes of Gloucestershire. But the excluding nature of a frame that demarcates ‘art’ from ‘not art’, and confirms the supremacy of sanctioned places of beauty, is misleading. Sequins shed onto asphalt shine as beguilingly as those stitched onto a gown.

Conventional ideas of decadence foreground costly ornamentation. Goldwork embroidery transforms a cotton dress into royal attire. A stone carver’s chisel shapes a block into an expressive face. A worked surface becomes a luxurious one because of the materials applied to and the time spent on it. But an appreciation of everyday beauty helps to shatter the monopoly that privilege and wealth hold over aesthetic experiences. In Everyday Aesthetics, Yuriko Saito proposes “bringing the background to the foreground”. We are encouraged to expect transcendence in rarefied places, whether natural or man-made. But what happens when we apply the principles governing art to everyday life? The unseen background of our lives is often formed by the unframed spaces we pass through – the Hellweg parking lot, the Oxford Tube, the Greifswalder Straße underpass, the Covered Market public toilets, even our light-starved breeze-block rooms. When we attend to the unremarkable, we transform it.

Take the detritus of an everyday walk. From hour to hour, street to street, our many steps send us past air conditioning units, surveillance cameras, drainpipes, fractured pavements, and even blunt plastic boxes that open up to reveal their innards of cords and wires and lights. Can the inside of a cable box be beautiful? Can the idea of everyday beauty be extended to enclose the sinuous curve of its red and white wires as they snake from plug to prong, the flashing red lights that display what is on, what is wrong? Rather than passively appreciating beauty which someone else has placed on a pedestal, how much better to discover what lies there for the taking. Recognizing and seeing everyday life as art is a way for our attention to co-author beauty – to frame, elevate, and call into being the very work we regard. We may cherish the fall of light through a bus shelter wall, even if – or precisely because – that glass is stained, that light a streetlamp’s sodium glare. Because this beauty often lacks a vocabulary for its articulation, it remains elusive.

Liberating ideas of beauty from inaccessible spaces means discovering transcendence in everyday life. And when schooled to tune into everyday beauty, the eye begins to alight on previously unnoticed places. Through a Turl Street window, you spot a book propped open by a mug with a tea bag slumped over its edge, splattering a page from Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus. Crossing the railway bridge at Dänenstraße, you observe how the coat of black on a brick wall has so thoroughly faded that the patches form a face. You turn a corner, and an iron railing paints a crisp silhouette on the sunburnt sandstone. And when you look over, the citric sharpness of a lime tree’s blossoms has sparkled the windscreens green. ∎

Words by Sylee Gore. Art by Violet Trevelyan-Clark.