What Remains

A pink scarf he bought that first Christmas together. Not that she ever wore scarves, which was why he’d bought it in the first place, and why he shouldn’t have bothered. (It snowed that January – more sludge than snow, really, the kind that produces muddy, misshapen snowmen – and she wore it then. When she joined him in the hallway, he said with pride: I bought you that.) After he moved out, she found it buried in the back of the wardrobe.

A painting they bought at a craft fair in town not long after they’d moved into their flat, of gondolas in Venice, water too blue to be believable. It reminded them of their first holiday: arguments at the airport; shoulders pink and peeling from sunburn; spending money they didn’t have. She still has the photo of them smiling in front of the sunset, after he’d spent the entire day complaining about the art gallery she made him visit.

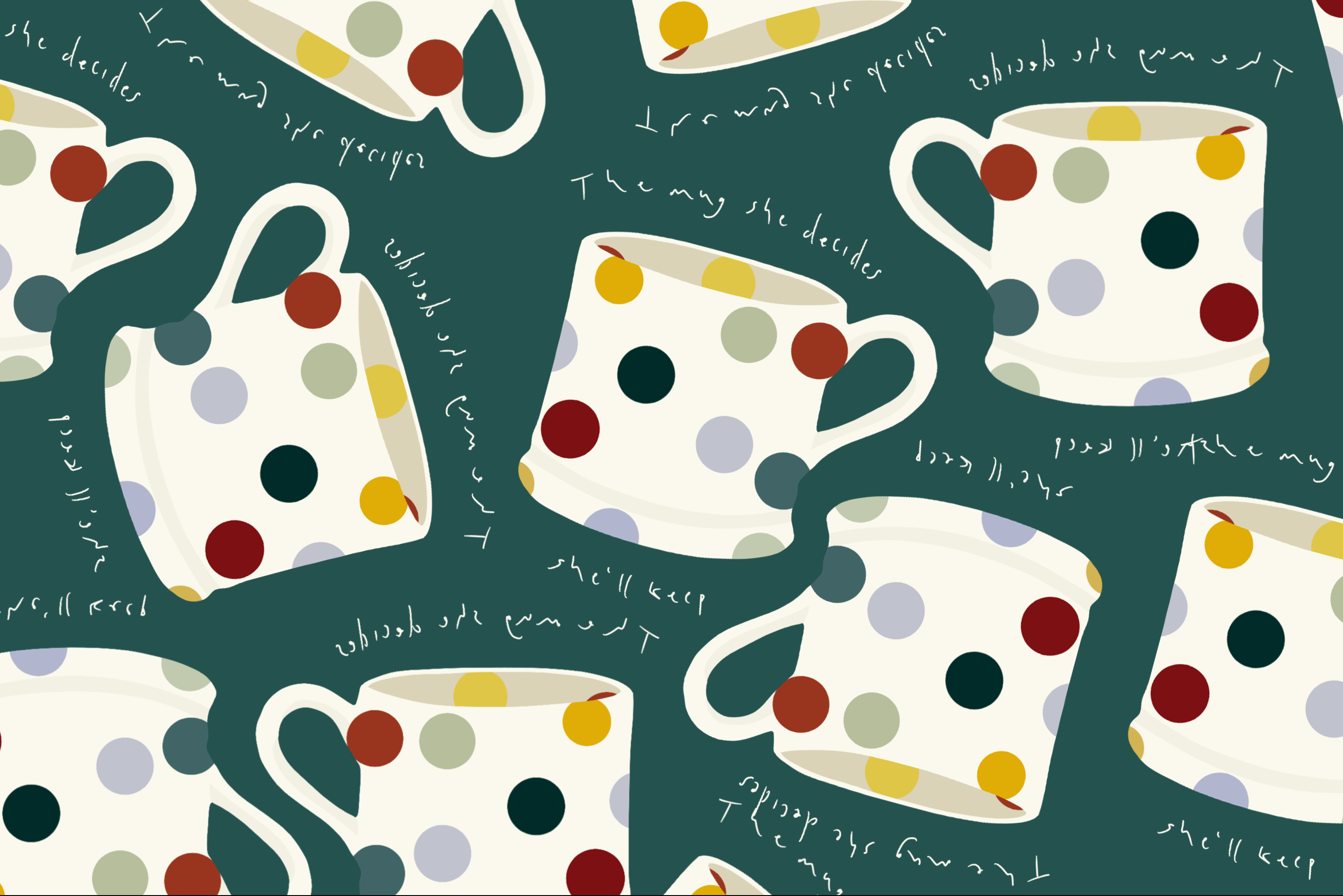

The Emma Bridgewater mug his mother had stolen from their kitchen (which she stole back the next time they visited his parents). That might have been the same visit his mother had run a finger along the top of the television and asked if she ever dusted.

Polaroids from Amber and Dan’s wedding last June. Blurred pictures of them dancing, wine and heels in hand, dishevelled hair stuck to foreheads. Whispered promises about his grandmother’s wedding ring. He had told her, three years, five Big Arguments, and countless Small Arguments ago, that it would be hers when they got married.

A note he left on her bedside table the morning he went away on a work trip, to apologise for calling her family suffocating. (She knew he didn’t regret the comment, so he had to sleep on the sofa for a night.) He wrote, at the bottom of the crumpled Post-it, that he loved her, which was by that point a lie. She found it tucked inside her collection of Dorothy Parker poems, a month after he had said they needed a month apart.

A vase (now in two pieces), white and decorated with an intricate blue design, which they had bought at the Oxfam next to the barber’s to make their new flat feel more like home. She had accidentally knocked it off the worktop, a fortnight before he left, but told herself she would try to fix it. The pieces are still in the kitchen cupboard, pushed to the back where she has allowed herself to forget about them.

The artefacts, preserved all this time, are laid out in a line on the living room floor, a four-year history condensed into sixteen objects from which she could cultivate a museum. She finds other things in the process of packing: the dress she’d worn on their first date; the black hoodie he wore to the gym; a half-empty bottle of aftershave; the cheap fridge magnets they collected from every place they visited; the cufflinks she had given him for his birthday; a receipt for the brunch place in town she’d been wanting to try for months; four Valentine’s Day cards.

The exhibit ends there, a far cry from the museums she visited as a kid. The relics aren’t protected behind glass, and there is no need for security guards to patrol the room (after all, who would think to steal a Post-it note?). There are no polished plaques, complete with dates and names. These stories won’t be found in any history books. As a footnote to the receipt, it could say that she ended up going alone, pancakes for one. Perhaps an empty space could be left after the fourth Valentines card, where the fifth should’ve gone.

One by one, she picks them up from the floor and puts them in a box, to be thrown away or donated to charity. (The mug, she decides, she’ll keep.) ∎

Words by Liberty Brignall. Art by Ben Beechener.