Seeing Double

Squirrelled away in Room 65 of the Ashmolean Museum are two remarkable landscapes. The paintings hang side by side in the Pissarro Gallery, surrounded by a collection of nineteenth-century pictures, and have done so for over a decade. They are, to wit, Camille Pissarro’s View from my Window and Vincent van Gogh’s Restaurant de la Sirène, Asnières. The careers of these masters neatly bookend the swirling currents of French Impressionism, a movement which, by the time of their vistas in the years 1886-8 and 1887, respectively, was in its twilight years. Their lives were markedly different: the longevous Pissarro, by many accounts a bon coucheur, would spawn an artistic dynasty to rival Renoir’s – quite unlike Van Gogh, whose sorry end and subsequent rise to fame are widely noted. Pissarro’s great-granddaughter, Lélia, runs a gallery in St James’s, and it was her great-aunt, Esther, who donated this paysage to the museum in 1950. In an exchange of fortunes, the painter who knew success within his lifetime fell into relative obscurity. He is just as likely to be mistaken for a marauding conquistador as he is to be recognized as père Pissarro, father of Impressionism. The movement’s myriad strains are marked by diverse approaches to perception and its transcription onto canvas. These Ashmolean landscapes are an invitation to look closer in the hope that one might eventually see.

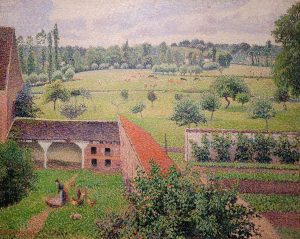

In 1884, Pissarro moved with his family to Éragny-sur-Epte, a quiet commune in northern France and the scene of this composition. While only a short train journey from Paris, the new environs were distinctly bucolic. He was presented with the pastoral scenes of a Millet painting, the kind actively sought by a young Van Gogh. But this calm spell in the country was to last only six years – by the final decade of the nineteenth century, Pissarro had returned to Paris, his cityscapes increasingly marked by the vicissitude of the seasons. The rentrée saw a reprisal of the variously urban and urbane subjects of his salad days. Van Gogh’s movements, meanwhile, were born of necessity: having grown so poor that he could no longer afford his modest rent in Antwerp, he came to Paris in February 1886 to lodge with his ever-supportive brother, Theo. A stroll away from his room, Asnières, the haunt of Seurat’s bathers, offered an ideal mixture of treed landscape and compelling exteriors. It was after this move that he met Pissarro, under whose counsel he turned to a more experimental brand of Post-Impressionism characterised by gestural brushwork and a lighter palette. This style was at the very forefront of pictorial innovation when, in 1890, he suffered a mors immatura at 37: the same age as Raphael.

Pissarro’s View from my Window is the larger painting. Were it not for his smart residence in the foreground, the scene would be ripe fruit for an eclogue. There is a rustic charm to this unremarkable episode of country life, an appeal that lies in its detail and, at first glance, its seeming fidelity to nature. The eye is drawn at once to the strong geometric form of a building in the lower centre, its slanting roof picked out with tiles of a dappled red. A mossed canopy juts out squarely from the wall, adjoining a barn at the extreme edge of the view. The precise boundaries of the poultry yard in the lower-left corner are thus enclosed, allowing a farmhand ample space to go about her duties. A small flock clucks away, as if in encouragement, as the eye jumps over the hills, where cattle court the cooling shade, hardly more than streaks of golden brown in a sea of greensward. Further yet, the barrow is circumscribed by a band of deepest pine. So is the soft lowing of the kine met with a sylvan silence; flora and fauna have reached a common understanding. These delicately handled swaths of land are harmonious in their juxtaposition, acting as modest foils to one another. To the left, lithe cypresses reach into the sky. To the right, the rampant foliage of a mighty trunk marks the landscape’s border. Every passage is treated with parity, and the picture exudes a gentle serenity.

The human eye is a curious, fickle thing: it is quick to fill in the gaps. The colour pink, for example, does not exist in nature. It is a postulate of the mind, cerebral shorthand for the wavelengths of light which the eye cannot process. Pointillism and Divisionism, which both fall under the parasol of Neo-Impressionism, knowingly exploited the corner-cutting processes of visual perception. These two prongs of avant-garde painting eschewed the narrative urgency and loose technique of Impressionism in favour of elaborately patterned brushwork and prescriptive colour theory.

Pissarro’s approach here falls somewhere between the two. It is a rigorous, quasi-scientific method, demanding the adjacent application of different colours that are then conflated by the eye and brain into an intelligible image. Often, contrasting tones are assembled into apparently seamless blends, with their contiguity lending the work a pronounced luminosity. The predominance of mauve tones in View from my Window, for instance, is remarkably subtle and carefully considered. Only at close range does one begin to notice stray purplish marks at every turn: in the shadows on the right-hand wall, between blades of grass, running up tree trunks. The temperature of this pigment is neutral. It acts in a largely unificatory capacity, silently adding cohesion to the work. Elsewhere, in the depths of Pissarro’s tulgey wood, scattered auburn marks counterbalance the otherwise overpowering darkness. Joris-Karl Huysmans lambasted this contrived technique and its chief proponents for their perceived superficiality: “strip [Seurat’s] figures of the coloured fleas that cover them, underneath there is nothing, no thought, no soul, nothing.” In thought and soul, Pissarro’s piece is not wanting. His œuvre is shot through with humility and paternal honesty, and this landscape above all is sedulously planned. Yet Huysmans’ point stings: however well-trained the fleas may be, they can only ever amount to a circus. Beneath its seductive chroma and inviting calm, Pissarro’s landscape lacks the impetus that distinguishes the most compelling pictures of the period. Individual passages sparkle with life, but the whole is compromised by a general want of motion. Conspicuously absent are the morning’s rosy oriflammes, or the spiral tension of an elaborate coiffure. Lost, too, is the immediacy of a bobbing petticoat, or an acrobat caught mid-flight. The vista is so carefully composed that it retains nothing of the pictorial entropy which vitalised nineteenth-century painting. Fortunately, Pissarro soon returned to a truer Impressionism, one which honoured the movement in spirit if not in letter, capturing and crystallising a scene, preserving moment as memory.

Van Gogh’s vista is altogether more restless. Nominally a depiction of the static Restaurant de la Sirène, Asnières, the canvas thrums nonetheless with a febrile energy. One keenly perceives the murmuring susurrations of the leaves, the restaurant’s fluttering flags, the concerted undulations of the turf. Yet, initially, the eye scurries down the slope’s crest to the meeting of navy blue and the more indistinct tonalities of the sod below. Seeking refuge from this uncomfortable encounter of order and disorder, one can either take the white steps which descend, ladder-like, from the hilltop, or climb the building’s concrete form, described in a bravura show of alla prima (wet-on-wet) mark-making. The eye ascends to the light sky, which seems to continue beyond the painting’s frame – a liberating departure from Van Gogh’s looming, colour-laden norm, which weighs heavily upon the ground below.

His use of negative space lends the landscape a tremulous vitality. The scene is legible enough. One can make out the trees, variations in the heath, and the separate floors of the building. Yet the supply of visual data is limited enough that the mind cannot fully summon the rest. One knows that there must be something in between Van Gogh’s coloured lines, but the eye is a cautious conjurer, reluctant to hazard a guess. This unrealised knowledge generates great tension: the painted marks oscillate in place, attracted to one another but sentenced to be apart. More tangibly, Van Gogh’s use of directional lines further augments this visual instability. The two prominent trees to the right sport leaves of blue and green that fan out from their trunks. The absence of any visible branches in this summarily worked verdure has a peculiar effect on the viewer’s perception. The foliage appears to ripple outward, shuddering in situ and quite unable to escape the confines of its position, like water locked in a pond. Where the restaurant’s regular, controlled lines impose order, these do the opposite. Not a stroke is wasted, and one feels that any more would have been superfluous: such is the painterly economy of a natural master.

The viewer’s presence is keenly felt, and the picture earns its title. It feels, without question, exceedingly modern, both for its execution and its great clarity of conception. Van Gogh’s confident grasp of form creates a convincing illusion of space and three-dimensionality in a two-dimensional work of art, where the focus is assuredly on the restaurant in the distance, and his daring experiment in upward-view perspective lends the scene great drama. Yet, upon closer inspection, the lower-middle register proves most rewarding. Its sharp acclivity is maculate in execution, sparse in coverage, and furious in intensity. Van Gogh has worked the land with a variously loaded brush. Many of the terre-verte and ochre strokes are consistent in thickness and pigmentation, dominating the grey undercoat inherited from earlier generations of French masters such as Corot and Prud’hon. The umber marks that line the bottom-right edge of this passage are strikingly different. They are characterised by a strong clump of colour – the point of impact – that fades upward, a gasp of the brush expressing the exhaustion of its pigment. The ultimate effect of this grand assembly is quite wondrous: spears of grass appear to leap out of the picture like flying fish, springing forth as the notes of Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila overture. As one is ushered out of the gallery and away from Asnières, one may cast an Orphic eye back at Van Gogh’s picture. The canvas hangs in its place, but the flights it conjured only moments ago have deserted the room as quickly as they came. For the briefest instant, the work was itself a paysage, not a painting.

In Pissarro’s Arcadia, there is no tomb. If anything, it borders on the saccharine. One would, however, do well to beware Van Gogh’s uncouth forest: there are tongues in his trees. The former’s adoption of a manner predicated upon artifice and calculation would find countless parallels in the twentieth century, with movements coming and going more quickly than they could be named. The latter, in his shift from harmony to dissonance, from tonal to atonal, emerged prescient. His process of visual deconstruction was a vitalising abstraction, giving new life by subtracting the superfluous. Herein lies the crux of these variously instructive pictures, and precisely why their juxtaposition proves so compelling. Pissarro’s Neo-Impressionist practice points to the mind’s intercession in sensory processing – the density of his mark-making is a barrier to the viewer’s creative impulses, which cannot be transposed onto the pictorial space. One is left to introspect, reflecting on the eye’s ongoing and intentional deception. Van Gogh’s canvas, meanwhile, is suggestive, inviting the intellect to overlay its assumptions upon sporadic strokes. That which must remain unseen throws the things we can perceive into sharp relief, illustrating that, in the hands of the mind, the eye is more a kaleidoscope than a simple lens. Soon lost amidst the imminent slew of secessions and the manifolding of manifestos was the uncommon humility of painters like Pissarro and Van Gogh, whose convictions lay beyond the commercial. They left only memories, remembrances of things past, of scenes lost, and of an endangered art. Van Gogh invests in his picture tremendous evocative potential: one is soon swept away to a field, trudging alongside the haggard brushman as he ventures forth, box easel in hand, to complete his third picture in as many days. A few acres away, old Pissarro sighs wearily, having added the final orb to his constellation with a practiced inclination of the wrist. The wind soughs softly through his room, but he scarcely gives it a thought. He closes the window at last, opening another in the Ashmolean. ∎

Words by Panayotis Galatis. Art by Faye Song.