Tagore and I

by Tridib Bhattacharya | January 11, 2022

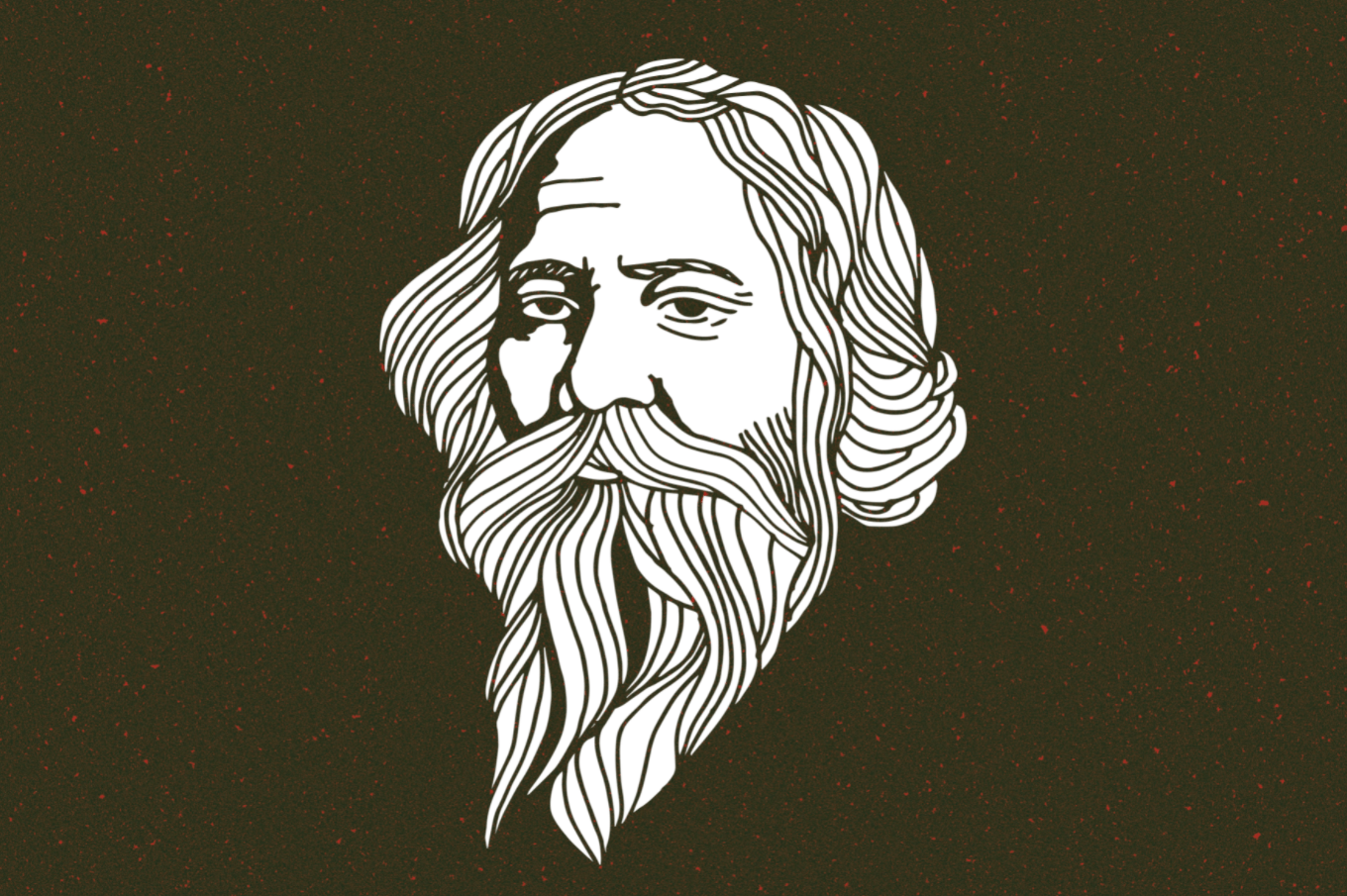

Rabindranath Tagore – renowned poet and composer, writer and artist, philosopher and polymath – has always been revered as a God-like figure in city-bred middle class Bengali families, and ours was no different. As a child growing up in the US, my understanding of God was limited to Ma’s daily prayers and the numerous religious festivals we celebrated. My awareness of Tagore was similarly restricted; I knew him largely as the namesake of my younger brother, who shares his birthday. Every other month, one family would host the rest of the local Bengali community for an evening music session – generally celebrations of Rabindra Sangeet, as Tagore’s songs are referred to. The adults would crowd into the living room, seated in a large circle on spare bed sheets with their instruments and copies of the gitabitan – a compilation of over 2,000 Rabindra Sangeet – while the children would entertain themselves inside. I however preferred to sit beside Baba as he animatedly played the tabla, helping pass plates of hot samosas around while listening to a language largely foreign to me.

It was only after moving to India as an eight-year old that I was gradually exposed to the man behind the wooden carving of Tagore’s face that sits in our family room. Numerous summer mornings were spent sprawled on the large bed in the guest room, as dida (the maternal grandmother) patiently taught me to recite Tagore’s poems for children. Dida, who herself took up writing post her retirement as a school principal, was overjoyed at our move to India; she saw no better way to broaden her grandchildren’s exposure to Bengali culture than through the works of Bengal’s foremost poet. What started as a chore – the echo of an American accent in my Bengali making things no easier – eventually became one of the highlights of my holidays, and dida found that getting me to sit still for an hour became an increasingly simpler task. Lines from Tagore’s verses I learnt over ten years ago linger in my mind even today. A child’s laments to his mother about the seemingly endless wait for Sunday and its pleasures are elevated by the undertones of economic inequality:

“Shom mongol budh, era shob ashe taratari

Eder ghore achhe bujhi mosta-hawa gari

Robibar she keno maa go, emon deri kore

Dhire dhire pouchay shey shokal barer pore

…

Shey buhji ma tomar moton gorib ghorer meye?

(Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday – they all come in such a hurry

Do they all own fast, expensive cars?

Why oh why mother, does Sunday come so late?

At a snail’s pace she arrives after all the other days

…

Does she, oh mother, come from a poor family like yours?)”

Like most other Bengali children, I was then inevitably enrolled in music classes – to learn Rabindra Sangeet. Although I could recognise some tunes from the communal music sessions in the US, I struggled to understand Tagore’s lyrical poetry and grasp his more complicated melodies. Nevertheless, there was always an intoxicating mix of fascination and pride I experienced whenever I would perform a song in front of my teacher, sitting cross-legged on the floor with the strains of an electronic tanpura in the background. Today, working on college assignments late into the night, Tagore’s music is my constant companion. There exists a Rabindra Sangeet for every mood, whether romantic or patriotic. Many of Tagore’s celebrated melodies in fact tread a fine line between dedication to a lover and devotion to the almighty (Amar hiyar majhe lukiye chhile/Dekhte ami paai ni – You lay hidden in my heart/And I could not see you); indeed in its most intense and passionate form, love for the almighty and a fellow mortal often merge into one.

* * *

With age, I have come to appreciate Tagore’s contributions as a writer, political philosopher and social reformer as well. Various volumes of his short stories and essays occupy my bookshelf – alas their English translations, as given the speed at which I read Bengali even an entire lifetime would not suffice. It was Tagore who pioneered the introduction of the short story in Indian literature. One of his most memorable stories is The Postmaster (1891), among his early attempts at portraying the voiceless women of rural Bengal. It follows a young, unlettered girl who grows attached to the new self-absorbed village postmaster, ultimately conveying that simply being empathetic to a fellow human requires neither age nor formal schooling. Many years later in 1917, describing his perceived failure of formal education, Tagore wrote “The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.” It was this ideal that Tagore sought to achieve with the foundation of the Visva-Bharati University at Shantiniketan in 1921. The independent curriculum was one that cultivated among students an understanding of the political, social, and environmental aspects of not just India but the world as a whole. This school, which introduced a number of teaching innovations including open-air classrooms, was one of the first co-educational institutions in India – and the modern education system arguably attempts to reflect many of the ideals Tagore first established at Shantiniketan (literally ‘abode of peace’).

As a politics student in this modern education system, Tagore’s writings on nationalism are particularly fascinating; he rejects the idea of artificially created nationhood in favour of naturally created human society, presciently noting that “nationalism is a cruel epidemic of evil that is sweeping over human world of the present age, eating into its moral vitality”. Similarly, Tagore’s conception of swaraj as encompassing not just political but also wider human freedom was subsequently reflected in Amartya Sen’s seminal capability approach to economic development, which views development as the expansion of human freedoms – social, economic, and political. Reflecting his humanist ideal, Tagore wrote of his ambition for “worldwide commerce of heart and mind”, beyond politicians who “wrangle about establishing trade relationships”. And in the aftermath of the 1905 Partition of Bengal on religious lines, Tagore’s reconceptualization of the traditional Hindu Raksha Bandhan festival honouring the relationship between brother and sister as a celebration of Hindu-Muslim fraternity – combined with his plays and novels against casteism and religious orthodoxy – remain especially relevant in today’s sectarian, polarised times. For Tagore, the true idea of nationalism was one that advocates unity and companionship between different faiths and communities, not one that sews divisions.

Tagore’s progressive politics in fact often took the form of poetic output. Songs he composed following the 1905 Partition, including ‘Amar Shonar Bangla’ (My Golden Bengal) gained immense popularity among the masses, serving as a rallying point for the Swadeshi movement which eventually forced the British to retract their decision to divide Bengal. Another song of resistance against the British divide-and-rule policy, ‘Bidhir Badhon Katbe Tumi’ (Are you strong enough to revert the course of destiny?) was composed to a rather joyful, seemingly incongruous tune. This façade was Tagore’s way of evading the eye of the police present at all public meetings attempting to gauge the general mood of the gathering; the British officers did not understand Bengali. Perhaps the most profound lines read “Shaasone jotoy ghero, achhe bal durbalero/Howona jotoy boro aachhen bhagoban (You may rule hard, but the oppressed resist harder/As great as you may become, the greatest is the almighty).

His position as both a literary as well as sociocultural icon mean that it would not be an exaggeration to call Tagore an architect of modern India. The country’s inaugural Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wrote in his famed ‘The Discovery of India’, “Tagore and Gandhi have undoubtedly been the two outstanding and dominating figures in the first half of the twentieth century…Not Bengali only, the language in which he himself wrote, but all the modern languages of India have been moulded partly by his writings”. Nehru went on to assert that “More than any other Indian, he [Tagore} has helped to bring into harmony the ideals of the East and the West, and broadened the bases of Indian nationalism.”. In Tagore’s vision for the future of his country and the world which Nehru alludes to, the celebration of reason and freedom are the two most prominent, recurring themes. This vision was expressed best by Tagore himself in a stirring poem, published in English as “Let My Country Awake”:

“Chitto jetha bhoy sunno, uccho jetha shir

Gyan jetha mukto, jetha griher prachir

Apon prangan tole dibashshorbori, bosudhare rakhe nai khondo khudra kori

…

Nijjo hoste nirdoye aaghaat kori, pita,

Bharoter shei shorge koro jagorito.

Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high

Where knowledge is free

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls

…

Into that heaven of freedom, my father,

Let my country awake”

The sheer volume of quality work that Tagore left behind is arguably unmatched in the literary world. Pandit Ravi Shankar, the distinguished musician, in fact remarked that had Tagore “been born in the West he would now be (as) revered as Shakespeare and Goethe”. Yet in my eyes, Tagore will above all remain a poet. It was his English translation of Gitanjali (Song Offerings), a collection of over 100 poems, that won him the 1913 Nobel Prize in Literature; he was the first non-European to be bestowed this honour. This was despite the fact that Tagore’s work can be incredibly difficult to translate, its nuances, intricacies and lyricism usually lost in between languages. Tagore’s essays and short stories I admire from afar, the head can appreciate his great intellectual and philosophical aptitude. But it is his poems, especially the lyrics of his songs, that have etched themselves onto the heart, that have added meaning to my life.

* * *

In 2011, on our first visit to Kolkata after moving to India, Ma and Baba decided to take my brother and I on a tour of the city. Visiting the Tagore family home and standing in the room where Tagore did most of his writing – at once both grandiose and quaint – I felt a strange but comforting sense of calm in my chest, as if I were temporarily at peace with myself and the world around me. In the years that have passed since that visit, the strange sense of privilege I felt to be standing on the ground on which Tagore once walked has gradually revealed itself to be entirely befitting; I have joined so many other Bengalis in venerating his creative genius and intellectual depth as something beyond us mere mortals.

As I write this in the wee hours of a typically cold, dreary London morning, my mind goes back to one of Tagore’s paintings that hangs in the guest room at home. Depicting a woman dressed in flowing robes, head covered and holding a large bowl, the caption reads “She is the woman ever so strange to me and yet I seem to know her”. Just like his bideshini – the eternal stranger from afar – Tagore is someone I have never met or personally known, and yet there is a distinctive, enigmatic connection to him I know I will always feel. ∎

Words by Tridib Bhattacharya. Artwork by Natalie Hytiroglou.