A Place of Sunshine and Death

I ran to her, for she was ██████████████ life as it had been. We had ██████████████████ ████████████████ the same river. As I ran, I thought, I will live with T. and I will be █████ her. Not ██ leave ███████. Not ████ Not ███████████the jagged ██████in her hand but ██████████████████ I did not feel███████only something wet, █████████ down my face ███████████████her face crumple up█████████████ We stared at each other, blood █████████████████It was as if I saw ██self. Like in a looking-glass.

Out on the terrace in my grandmother’s house in Westmoreland, the night was sweet with night-blooming jasmine and the sky was pulsing with a multitude of stars you couldn’t see in Toronto.¹ The clothesline creaked slowly in the breeze. A row of blue rain barrels against the wall, filled to the brim with rainwater, reflected the flickering of moonlight. This place could claim me now and I wouldn’t mind, I thought. I wouldn’t mind at all. In that moment, I wanted nothing more than to return to this land where my family was from, to be anchored to it, to not have to think about belonging to more than one place anymore.

Down below, a single lightbulb flickered on in the garage.² My cousin T. emerged from the darkness, stepping into the warm pool of light, a basket wedged under her arm. She moved slowly and aggressively, almost too sensual for a girl of fifteen. She stood in front of the rain barrel, her blade body between the car and the wall, washing her clothes with runoff water.

This was something I would never do. To go outside after dark to do, of all things, chores. In my mother’s house in the suburbs of Toronto, my friends and I applied pink lip gloss and swapped lacy tank tops, a CD by Usher playing from my expensive speaker system, before a car filled with boys drove us to a house party. My favourite drink was fireball whisky, the one that tasted like melted cinnamon hearts. My second favourite was a vodka spritzer called Growers. Recently, I had sex with a boy in exchange for a pack of cigarettes.³

I didn’t know much about T. aside from what Grandma told me. I had been to Jamaica a dozen times, but this was the first time I’d seen her.

She tief, Grandma had told me that morning. Ma and Grandma had sat at the kitchen table in their black dresses, panty hose, and high heels, eating their ackee and breadfruit without appetite. I had asked why T. wasn’t invited for breakfast on the day of her father’s wake. She take money from me handbag, Grandma had replied. T. not welcome here.

That’s why T. was staying downstairs, in the apartment that belonged to her father and his wife – the woman who was not T.’s mother.

In a way, I envied T. She could go and come through the front gates of the house as she pleased, while I was not allowed to leave Grandma’s property unless I was in a car. The windows and doors of Grandma’s big white house were covered in steel security bars, which made me feel like a prisoner.

⬥

I knew A. was watching me from the terrace. Let her watch, she with her pretty things. Just she wait. One day, I will have pretty things too.

Grandma asked me to take the money to the post office. The bill got paid, didn’t it? Grandma forgets why she give me money; she is at that age.

Grandma always say I am not part of her family. One time, I ask why. Because my mother was her son’s girlfriend, not his wife? Because I am dark? If I had been the only outside child, maybe the situation would have been different. But Daddy had six pickney like me.

In Kingston, they call me Chiney girl everywhere I go. Ironic, isn’t it? One man who run a beauty pageant even say I should sign up. Him say Chiney girl do well in Jamaican pageant.⁴ To Grandma, I am not Chinese enough. To everyone else, it’s all they see.

When people see Chiney, them see money. To the people I know, money is the most beautiful thing in the world.

⬥

Under the raw lightbulb, I watched T. rinse away the salt and grime from her dress. Suddenly I was in a white-walled room in a hospital ward in Toronto. On the bed was my father. For months, he had been hooked up to wires that made his eyelids peel back in hallucinations. On that morning when the illness finally claimed him, there were no more wires on the bed. There was a window at the far end: autumn leaves of crimson and gold illuminated by a stark morning sun. I was the only one who touched him. Sat in a chair beside him, I stroked his cooling hand and leant my head against his chest, staining the thin robe with tears. Ma and Grandma stood several feet away, not wanting to go near death.

Grandma pulled on my arm. Time to go, she said.

I dutifully followed.

Grandma paused at the threshold. Wash your hands first, she said, giving me a push towards the sink.

Without thinking, I washed my hands, turning on the tap and pumping the soap dispenser. As the cool water rushed through my fingers, I realised with horror what I’d done: I washed away the last traces of my father right in front of him. I had never felt more cruel. I never forgave Grandma for making me do it.

Tomorrow would be the funeral of T.’s father, a man I only knew through stories of family shame: the blacklisted prize-winning racehorse trainer, the cockfight organiser, unable to emigrate to Canada because of his criminal record, his illegitimate children scattered across the island, kept secret from Grandma and his wife until he couldn’t support them on his own.

At his wake, the six children stood in their suits and dresses with tears streaming down their faces. Daddy was a good man, they all said.

It was then I realised that the only stories I heard about my family in Jamaica were from Grandma.

⬥

I dunked my dress in the rain barrel, squeezed the water out with my hands, then placed it on the edge of the barrel. It was the one nice dress I owned; I had worn it at the wake and would wear it again at the funeral. In between, I must wash it.

I looked up and saw A. coming toward me, through the garden.⁵ She stopped opposite the barrel but didn’t say a word.

You’re in all the photos on grandma’s wall, I said. A. had a light complexion from her Daddy.⁶ But she had the same eyes, broad cheekbones and bow lips just like mine––unmistakeably Chinese.

It’s because I don’t live here, A. replied, embarrassed.

Does A. know that even though Grandma say I am not part of her family, and she call me tief, every summer she send her driver to Kingston to collect me? That I live with her every summer? I am the secret child, the one they don’t speak about or have picture of, but I am loved too. That’s what she don’t know.

I’m going to leave here one day too, I say. A. nods as though she so sure it will happen for me. Like if I want to go, all I must do is say so.

⬥

Standing over the rain barrel with the raw lightbulb above, I noticed our faces in the water, like a looking-glass.⁷

⬥

When I returned to the suburbs of Toronto, I resumed drinking and smoking until I was numb to the world again.⁸ I talked to T. once: I wished her Merry Christmas on WhatsApp and T. responded with the same words and a Santa emoji.

The next time I saw T. was four years later, at Grandma’s funeral in Westmoreland. I was reading English at Oxford then.⁹ It was between terms, so I was able to attend the funeral despite my towering pile of schoolwork. I wore flats to walk from Grandma’s house to the church and then forgot to change into my heels for the ceremony and pictures. T. wore a black dress with a plunging neckline that showed the stretchmarks on her breasts, her hair dyed bright red. When I first saw her, T. and I hugged, just once.¹⁰

The reception was on the terrace at Grandma’s house. T. showed me a photo of her baby son on her phone.

⬥

I slept in the chair beside Grandma’s bed until she pass. She would have nightmares sometimes. I didn’t want to leave her. I sat beside her and stroked her hand until she fall asleep again, night after night. Just the two of us.

A. is the one who give speech at the funeral. A. is the one who write the story, alone, in England.

But I’m the one who was with Grandma, who she truly love, and truly love her.

⬥

I remembered the last time I’d been here, when I believed I wanted to live in Westmoreland, to spend the rest of my days eating mangoes from the tree, juice dripping down my chin, dancing in dark clubs that clung to the sides of mountains as though they were about to tumble to oblivion.

Grandma’s house was empty now. I could return anytime I liked, could even claim it as my own. I could have one home instead of several pulling me in different directions.¹¹

I could almost see the tendrils crawling up T.’s legs, rooting her to the land.

A few days later, after I dragged my suitcase heavy with books to the airport, I watched the island disappear from my airplane window.¹²

¹Rhys, Jean. Wide Sargasso Sea ██████& Company█████

Our garden was ██████ beautiful as that garden ███████ –██████ of life ███████████████████████

█████████ overgrown ████████dead flowers mixed with █████████ living █████, 19.

² Blot out███████ pull █████████ love in ███████████ for the dark ██ soon, ██ soon, 139.

³ I let the dress fall █████████looked █████████to the dress ████ from ███████ the fire, 186

⁴ Pretty ████████████ colour –– ███ yellow ████ me, 126.

⁵ █████████████████████████████████the end of the garden. ████████████ green ███████ as velvet ████████████████ 25.

⁶ ██████ yellow ███ like me ██?, 125.

⁷ ██████ then ████ I saw █████ the ghost. ███ woman ████████████████ surrounded by a ████ frame ███ I knew her, 188.

⁸ I was always ███████████████████████████████ █████████████ after sunset, █████████████████ haunted, some █████ are, 132.

⁹ ████████████████████ their world. It is, as I always knew, made of cardboard███████████████████████████████ █████We lost our way to England .█████████████████ ██████████████ 181.

¹⁰ ██████pretend ███████████ one day it falls away and ███████████We are alone in the most beautiful ███████ world.

¹¹ ███████████████████ who I am ███ where is my country ███████ do I belong ███ why ██████████at all.

¹² █████no looking-glass ████ █████████████████ █ ██████████████████████████████ I tried to ██████ ███████████████ between us – hard, cold███████████ ████ my breath. ███ they have taken ███████ away. What ██ I ███████████████am ██ 180.

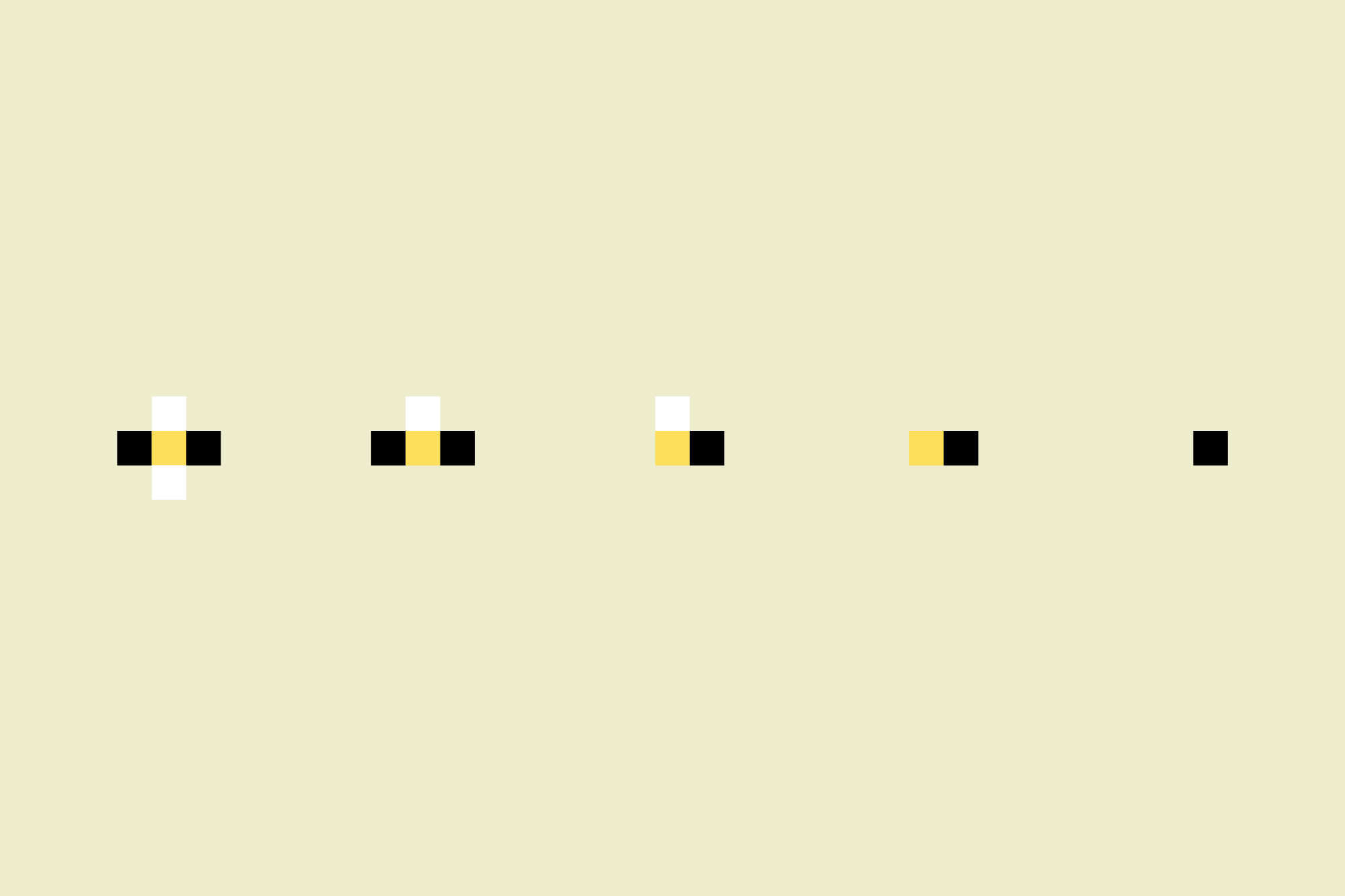

Words by Joanne Szilagyi. Artwork by Millie Dean-Lewis