The Big Queer Monster

For weeks after the release of ‘Montero (Call Me By Your Name)’, Lil Nas X’s Twitter mentions were filled with homophobic slurs and Bible verses. At this point, it’s almost impossible not to have seen the music video for ‘Montero’, or at least the memes of Lil Nas X pole dancing his way down to the gates of hell and giving Satan a lap dance. The sexual content and religious imagery in the music video sparked controversy, and a flurry of articles from detractors and supporters alike have come out in the two months since its release. Yet it is in these discussions of the music video’s aesthetic choices where I think critics are missing the mark. There is a deeper meaning present here beyond mere marketing tactics to court controversy. In light of Lil Nas X’s comments on his internalised homophobia as a young teenager, one such reading emerges. The imagery of ‘Montero’ shows a reclamation of the demonic monstrosity pushed onto LGBTQ+ youth, remoulding homophobic narratives into a source of liberation and power. The conservative backlash to the music video proves one thing clearly – the image of the queer monster, when reclaimed and celebrated by LGBTQ+ artists, is as potent as it is provocative.

Queerness and monstrosity share a long history. Across centuries and cultures, monsters appear as stand-ins for marginalised groups. Those who do not conform to mainstream culture are demonised, transformed into vampires or werewolves so that we can paint them as enemies and Others. Though this ‘monsterisation’ is applied across all axes of social difference, most commonly it is ethnic, religious, sexual, and gender minorities who are made monstrous. And thus, the queer monster is born. The horror genre is notorious for this, because what better shorthand is there for demonstrating a villain’s perversity and depravity than queer-coding? Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) is not monstrous solely because he is a murderer – he also cross-dresses as his mother, adopting her persona in a grotesque misrepresentation of dissociative identity disorder. In the eyes of a straight audience, Bates’ queerness compounds his monstrosity. And while Psycho is not the only horror film to use queer-coding to intensify the fear factor of its villain, the open secret of its lead actor Anthony Perkins’ queerness makes it one of cinema’s more insidious examples.

Whilst the queer monster trope has been used to demonise LGBTQ+ people, there is the inverse tendency for queer audiences to sympathise more with the monster than the supposed protagonists. Dr. Harry M. Benshoff, a professor who writes on queer monstrosity in film, notes that “both the monster and the homosexual are permanent residents of shadowy spaces”. Benshoff speaks only of “the homosexual”, but that same theory applies to the entire LGBTQ+ community, whereby identification with the monster is the natural result of a marginalised existence. We see ourselves reflected in the monster because we recognise the pain of being ostracised for our uncontrollable differences. So, while straight writers and directors might use queerness and even queer actors solely to denote the monstrous villain (as with Anthony Perkins in Psycho), queer artists offer alternative interpretations of queer monstrosity. With this comes a growing trend of sympathy for the monster in fiction, from films like Edward Scissorhands (1990) and Shrek (2001) to TV shows like In the Flesh (2013-14) and Black Sails (2014-17). No longer typecast as the villain, the monster becomes the protagonist.

In my opinion, the appeal of the monster protagonist for LGBTQ+ audiences comes from its defiant rejection of the society that seeks to wipe it out – unapologetic and unashamed in its difference from the mainstream. Where some LGBTQ+ works like Love, Simon speak to a straight audience to the tune of ‘we’re just like you’, art with monstrous imagery like ‘Montero’ addresses queer audiences directly. Queer monster narratives tend to have more limited viewership than their more conventional counterparts, but their message is no less potent for this. Positioning the queer monster as the protagonist, in projects helmed by queer creatives, allows the marginalised individual to define themselves on their own terms. In contrast to films that rely on homophobic stereotypes to create monstrous queer-coded villains, works with queer monster protagonists offer a first-hand vision of life from the margins. The monster-as-protagonist forces us to reconsider which narrative we want to listen to – the tired stereotypes that demonise the LGBTQ+ community, or the personal testimony of queer artists themselves?

‘Montero’ inherits this trope of the queer monster protagonist and brings it into the mainstream. Lil Nas X has been open about his internalised homophobia as a teenager – his Christian upbringing made him ashamed of his sexuality, and he used to pray for his queerness to be just a phase. “I never wanted to be gay,” he said in an interview with Jamal Jordan for GQ. “I even thought, ‘If I have these feelings, it’s just a test. A temporary test. It’s going to go away. God is just tempting me’.” Lil Nas X clarified his personal links with ‘Montero’ in a letter to his fourteen-year-old self he posted on Twitter the day the video dropped, and his past self-hatred informs the powerful combination of religious imagery and demonic monstrosity in the music video’s aesthetics. In perhaps the most infamous sequence of the video, Lil Nas X ascends towards an angel ready to welcome him to heaven. But a pole suddenly appears behind him. Nas chooses to pole dance to hell, down towards the eternal damnation that young queer individuals are threatened with. We witness Nas reclaiming the narrative of his own sexuality, deciding for himself what his queerness represents. He chooses liberation from judgement – Nas goes to hell on his own terms, rather than because others have condemned him to it. With that liberation comes the freedom to be exactly who he wants. After seducing Satan with a lap dance, Nas snaps Satan’s neck and removes his horns, placing them on his own head. Eyes glowing bright and wings flared out behind him, the music video ends on this powerful image of Lil Nas X, transformed and triumphant.

The responses have been varied, to say the least. As the negative backlash has been detailed elsewhere, my focus here is the response from LGBTQ+ audiences. For both long-term fans and newer queer listeners, the significance of ‘Montero’ is hard to overstate. Religious homophobia is sadly still common, and the music video not only reflects the trauma that comes with this type of upbringing, but also provides a comforting counterpoint in its embrace of queer monstrosity. Benshoff’s aforementioned argument that monsters and marginalised queer people dwell together in “shadowy spaces” seems to ring true in Lil Nas X’s creation. ‘Montero’ takes this idea and runs with it, showing the power and potential that come through celebrating the ties between queerness and monstrosity – even hell itself can be transformed when it is re-framed through the lens of queer monstrosity. With the 30 second clip of Lil Nas X pole dancing his way down to hell, the bite is taken out of the barb that ‘all queer people go to hell’. Religious homophobia is defanged, made impotent, and for Nas’ older and younger fans alike, this could be lifesaving.

The demonic transformation of Nas at the end of ‘Montero’ suggests that the best way to shake off the shame caused by internalised homophobia is to embrace queer monstrosity. In the week immediately following the video’s release, Nas’ Twitter mentions were flooded with people saying they’d never seen anything like ‘Montero’ before, “thank you” appearing over and over again. Evidently the video’s message hit its mark. One tweet, thanking Lil Nas X for his representation of “alternative Black queerness in mainstream” music, raises another point about ‘Montero’: the video constitutes a major step forward for the self-representation of Black queer artists. As Jamal Jordan writes in Lil Nas X’s GQ interview: “Here’s a young gay Black man, doing whatever the fuck he wants, and losing absolutely nothing for it. It was something I, like so many other LGBT Black people, have always wanted to see.” The intersections of Nas’ identity make his portrayal of queer monstrosity even more meaningful. The impact of this representation for Black LGBTQ+ audiences is compounded when you consider the reach of Lil Nas X’s work. The viewership of ‘Montero’ alone far exceeds most mainstream queer music. As of writing this, 233m people have watched Lil Nas X sing on YouTube about having sex with men, explicitly and without shame. ‘Montero’ is one of the most ground-breaking depictions of the monster in queer art in years, and this is due as much to the sheer immensity of the video’s reach as it is to the work’s central message of radical self-acceptance.

This music video showed far more clearly what my dissertation, submitted the same day ‘Montero’ came out, spent 15,000 words trying to argue: we are worth more than what is said about us by homophobic, transphobic bigots – and even if we are monsters to them, so what? There’s freedom in embracing monstrosity, in reclaiming the narrative to define ourselves in our own terms. Where in the past, queer artists and actors had to work within hateful stereotypes, there is now space for different approaches to queer monstrosity: art by queer people, for queer people. Artists like Lil Nas X transform the “shadowy spaces” where we dwell with monsters into places of joy and liberation. The aesthetics of ‘Montero’, written off by some critics as a savvy marketing tactic, become more poignant in light of this history of queer monstrosity reclaimed and celebrated by LGBTQ+ audiences.

Lil Nas X is more than self-aware of the significance of ‘Montero’ on this point. In the letter to his fourteen-year-old self, he writes: “I know we promised to die with the secret, but this will open doors for many other queer people to simply exist. You see, this is very scary for me, people will be angry, they will say I am pushing an agenda. But the truth is, I am. The agenda to make people stay the fuck out of other people’s lives and stop dictating who they should be.” The demonic monster we see at the end of ‘Montero’, triumphant in his hellish transformation, offers us a new form of queerness that revels in uncompromising difference from the straight mainstream: a queer sexuality that can’t, and won’t, be repressed any longer.■

Harry M. Benshoff, Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film (1997).

James Somerton, Monsters in the Closet – A History of LGBT Representation in Horror Cinema (2018). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4zPCM14-SCQ

Michael Elias, “Queer Monsters: The Importance of Monstrosity in Queer Storytelling” (2020). https://thewrangler.org/2020/06/18/queer-monsters/

Jamal Jordan, “Lil Nas X: ‘At first I felt a sense of responsibility. But now I just don’t care’” (2021). https://www.gq-magazine.co.uk/culture/article/lil-nas-x-interview-2021

Ira Madison III, “Lil Nas X is here to prove you wrong” (2021). https://ew.com/music/lil-nas-x-montero-pride-cover-story/

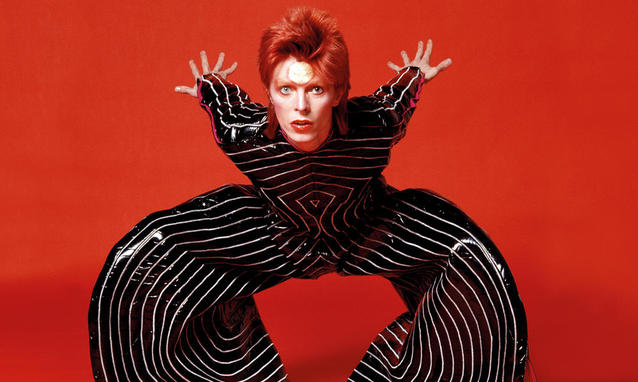

Words by Kiera Johnson. Artwork by Natalie Hytiroglou