My Mother, After

When my mother’s hair came back slightly thicker, she decided she wanted to dye it bright blue. My dad put on the colour as she sat with a towel wrapped around her shoulders in front of the bathroom mirror. I remember that when she turned to look at me: the frantic smudges around her hair line looked the colour of woad, Boudica’s battle paint.

Before chemotherapy, her hair had been dark red, shoulder length and curly: it was a huge part of her hippy identity, the way she styled herself in 70s prairie dresses and pink cowboy boots. Before, she’d sometimes fret about her fringe being in the right place to cover the parts of her forehead she didn’t like, sitting in front of her mirror with straighteners as we discussed what she planned to wear to work. Last December, after her first chemo session, she chose to cut off her hair before it fell out. It was “a way to gain control”, she told me, a chance to “turn it into something powerful”. As part of the process, she filmed it and posted the video on Facebook. I still feel now the surprise of the notification, stuck in Oxford while all my family was back home in Stoke. It was strange watching her at the other end of the country, sitting with scissors at the kitchen table while my little brother nervously laughed behind the camera. As she cuts the curls, she speaks: “You are not your hair, you are not your boobs, you are not your eyebrows – you are the people that love you, and you are what you do in the world.”

In little ways, as well as in big ways, cancer has changed my mum. Who people are after cancer is a scary thing we don’t often think about. When we are around people we love who are dangerously ill, all we want is for them to get better, for the whole world to be normal again. Normality is something we all crave, tinged as we are with nostalgia for days before a diagnosis.

Today, when headlines are flooded with this idea of ‘the new normal’ in the light of the pandemic, I can’t help but think how aptly it applies to my mum’s life after her treatment had finished. When my mum was first diagnosed with breast cancer, this was a phrase my dad would often say: “we have to get used to a new normal”. It was a ‘we’, a collective, a community of mutual familial support to help my mother as much as we could through the trials of surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy. We used it to emphasise our nature as a family unit as a way to keep us together in a world that seemed to be rapidly falling apart. It was a reminder of our ability to adapt together. When I think about the language of solidarity we took so much effort in employing, I wonder at this phrase, and how everything already difficult became a little harder. Because, of course, my mother recovered from cancer in a pandemic.

Though neither her chemotherapy nor her radiotherapy was delayed or cancelled due to COVID-19, when so many others’ treatment was held back, her last chemotherapy sessions and the entirety of her radiotherapy occurred whilst we were under increasing lockdown restrictions. My mum doesn’t like to complain about this. Perhaps she was lucky to be having treatment at all, but there is no mistaking how difficult it is to go into cancer treatment entirely alone. My dad had been by her side during every chemotherapy session, but had to wait in the hospital car park as he was now unable to step into the building. My mum suffered allergic reactions to docetaxel during her last chemotherapy session without him there. She had the dotted tattoos for radiotherapy alone. She rang the bell to signify the end of treatment without any of her family around her. This moment especially should have been one of celebration, a last big battle cry to rejoice that she had reached the end; it was also something my mum had been looking towards with hope. “The bell had become this golden bell. I thought I would have my husband with me, my children, at least my son, with me”, she tells me. There’s a picture of her ringing this bell taken by one of the nurses, but my mum doesn’t like it. She says she doesn’t look well.

I didn’t get to be with my mother through her surgery, or much of her chemotherapy – we kept in contact during term through frequent messages and the odd phone call – but I did get to be there for her afterwards. So, I came to know, at least a little, what it means when a recovering cancer patient can’t start stepping back into the world again. I can understand, just a tiny bit, that it is very hard to be sent home with a warning to check for recurring lumps, to be told to think of yourself as cancer-free, with nothing to truly distract you from burns, and scars, and the fear that it’s all going to come back. Without in-person aftercare appointments, my mum’s anxieties were worse – she would worry about the scar looking abnormal or the burns being too severe. When she attempted to book a GP appointment to check these burns, the receptionist requested images. “It was so ugly, so painful I didn’t want anyone to see it,” my mum admits.

There are other little things which hurt too – events that should have been joyous but were tinged with loss. After her treatment finished, we dressed up and ate cake outside in the sun. Over prosecco my dad made a toast, a celebration of the beginning of something new and apart from cancer. It was just us four. My grandparents should have been there, so should my aunt and uncle and cousin, but they simply couldn’t because of the lockdown. My mum had so many plans to celebrate being alive. She was going to go on holiday to Whitby, her favourite place in the UK: when that got cancelled, she told me how the last time she was there she’d had a strange feeling she’d never see the seaside town again. Now a small and superstitious part of her was convinced she never would, and that belief fed her fears of cancer returning. There were plans to follow old pilgrimage routes across the UK with my dad, inspired by previous trips to Lindisfarne and the comfort she had found in God, but these were also cancelled. Called-off holidays are minor inconveniences; she tells me repeatedly she does not want to seem like she is whining. But that long golden summer after treatment– the months-long stretch that was always there as a promise or a goal, a sign to show that she still had the whole world to look forward to – had been taken away. Today, “where the cancer treatment ended, and the pandemic began, has blurred indefinitely.”

Talking to others helped. The local Staffordshire breast cancer support group Pink Sisters (And Misters) has been invaluable to my mum, providing a community for patients to talk about cancer without any pressure to seem like things were ‘back to before.’ My mum met Jackie Mackenzie, who began the Pink Sisters five years ago after recovering from breast cancer, at a social distance when lockdown restrictions eased. They spoke about her worries for hours, as Jackie offered her own experiences with cancer in a way that helped to assuage nagging concerns and reassure my mum of her strength. The power of a chat is something that cannot be underestimated. My mum often comes back from group meetings feeling grounded, having spoken to people who are living, who are positive and powerful individuals. It helps her feel like a warrior, knowing she always has a community of people who can truly understand; talking to people who are five, ten, or fifteen years out of treatment often helps her to cope with the anxieties surrounding a disease that doesn’t truly go away, that looms over you like a threat. “People need to recognise that just because someone’s stopped treatment, it’s not back to normal, it’s a new normal,” Jackie explains, using that phrase once more.

It was October when my mum told me about her diagnosis. She sat me across the kitchen table a few weeks before I left for University and admitted it: they’d kept it quiet for a week or so, to try to figure out what to do, but I’d sort of known already. My dad had started making declarations, long term promises of a greenhouse moved up to now. He’d held her hand just slightly more. And my mum, a few days before she’d told me, had walked me and my little brother down the field to release a frog my granddad had found stranded. As it crawled away into the grass, she turned to us. “We’re so lucky. It’s like heaven down here,” she said, a little as if she might lose it.

I think quite often about the fragility of before, that handful of days when I didn’t dare ask. I think about how I put my head down and cried on that kitchen table, how I felt so entirely useless, so impossibly unhelpful. The fragility of afterwards is different. It has a lot more grit. Over lockdown sometimes I would catch my mother planting tomatoes, or drawing her eyebrows on in the mirror, and learn every time something new about strength.

“It would have been nice to be in a normal world.” My mother laughs at little. “But I am really happy to be breathing. Although it’s not the normal I was expecting or aiming for, I’ll take it because I’m alive.”

We talk about hair in terms of future plans now, the colours to dye it next. The growing fuzz when chemo ended was “like seeing a snowdrop at the end of a garden in crappy, cold weather” but my mother also knew she didn’t want her long curls again; “I didn’t want to go crawling back to an identity that had changed, as though it was all about loss,” she says of her short blue buzz cut. It is ironic, she notes, that the summer before her diagnosis she had been tempted to have all her hair cut off but decided against it– she’d thought her hairline was too high. Without the cancer she would never have been proven wrong: “People say I like your hair and I can go Oh do you? and I can say I love it too. And when it gets long and thick, I can buzz it off again because that’s who I am and that’s who I want to be.”

A few days ago, she sent me a photo of her buzz cut dyed pink.∎

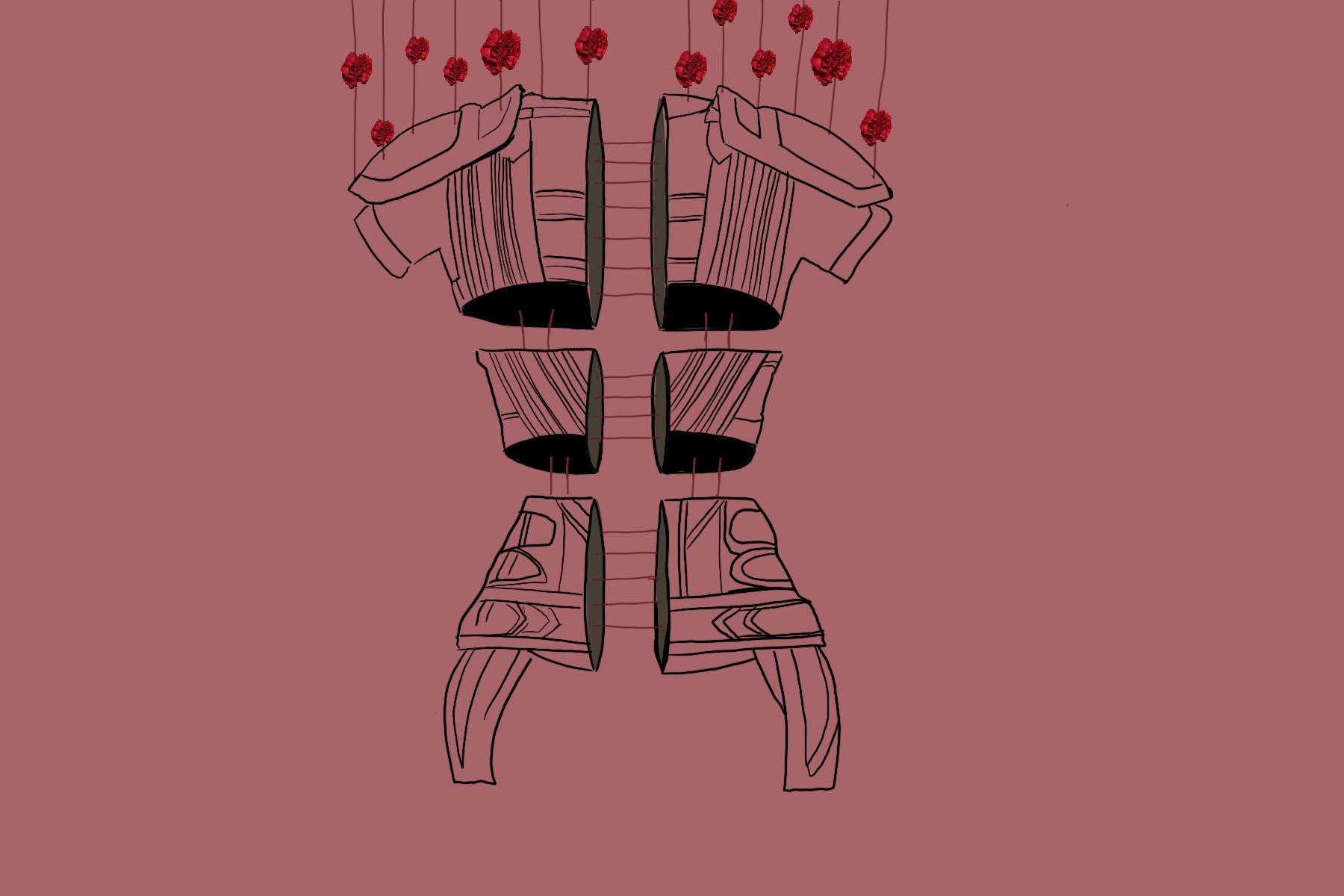

Words by Matilda Houston-Brown. Art by Sasha LaCômbe.