A Brief Cultural History of the Cane Toad

Yesterday, I took out the kitchen compost. As I flung it into the bin, there, sitting on the rubbish, was a big fat cane toad. Revulsion flowed through me — and then, just as quickly, nostalgia. Is there a more Australian sight? Shocked, I reeled back: when did my mind transmute Australia’s most hated critter into a symbol of home?

The cane toad is famed for warty skin, poison-secreting glands, a bony ridged brow—and for being

detested by Australians. I cannot remember when I became aware of the existence of cane toads.

Growing up in Queensland, it was something you took for granted: summers were too hot, we were

always in drought, and cane toads were to be loathed and destroyed. National Geographic describes

them as ‘much maligned’; the World Wildlife Fund puts it diplomatically, stating that the toad has

‘developed a bad reputation’; while the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 lists the growing cane toad population as a ‘“key threatening process’”. And yet, in this righteous hatred, is there a little wart-shaped nugget of affection for the critter? For those unfamiliar with the story, the cane toad (rhinella marina) is the most famous and ecologically disastrous case-study of an “introduced species”. In 1935, the Australian Bureau of Sugar Experimental Stations brought 102 cane toads from Hawaii to Meringa Station near Cairns, Queensland. They bred around 24,000 toads and released them into north Queensland’s sugarcane fields to help control cane beetle infestations which were damaging crops. It was an

abysmal failure. The cane toads were unable to jump high enough to reach the adult beetles (which lived on the upper stalks of the plant).

Despite this failure, cane toads thrived, adapting to the Australian environment— and spreading at

an astounding rate. As of 2019, the WWF estimates that there are over 200 million cane toads in

Australia, spreading across the country and damaging the environment. Following the arrival of cane

toads in a region, local wildlife populations decline: snakes, goannas, quolls, and many other native

species are either pushed out of their territory (unable to compete for food and shelter with

the rampant toad) or else they eat the toad and are subsequently poisoned by its

milky-white bufotoxin.*

“Introduced species” have a long and troubled history in Australia. Cats, camels, deer, boar,

and rabbits—in fact, most domestic species brought by white settlers—are considered pests due to the way

they damage Australia’s native ecosystems. Under most rubrics, the settlers themselves

would be considered introduced species—but, unsurprisingly, the makers of the taxonomy

didn’t think to include themselves. In many ways, the cane toad problem

epitomises the hubris and senselessness of seeking to solve problems by transporting living

creatures to foreign places. The Queensland Museum concludes its cane toad database entry with

elegiac incomprehension: ‘”The full impact of Cane Toads on our wildlife may never be fully

appreciated.’”

Despite the widespread despair at ever being able to manage the toad spread, there are

many energetic local organisations that aim to protect vulnerable ecosystems. The Kimberley Toad

Busters of Western Australia proudly proclaim on their logo, ‘”If everyone was a toadbuster, the

toads would be busted’”. These groups are the definition of grassroot community action: many

of the toadbuster groups revolve around planning ToadMusters in their local parks. The

Northern Territory based ToadWatch elucidates: “‘ToadMusters are when people go out and collect

toads at night. You can do this in your backyard or the local wetlands.’” Advice includes bringing high-

powered spotlights to the muster and maybe using a small net, ‘”but we just use our hands, gloves

optional.”’

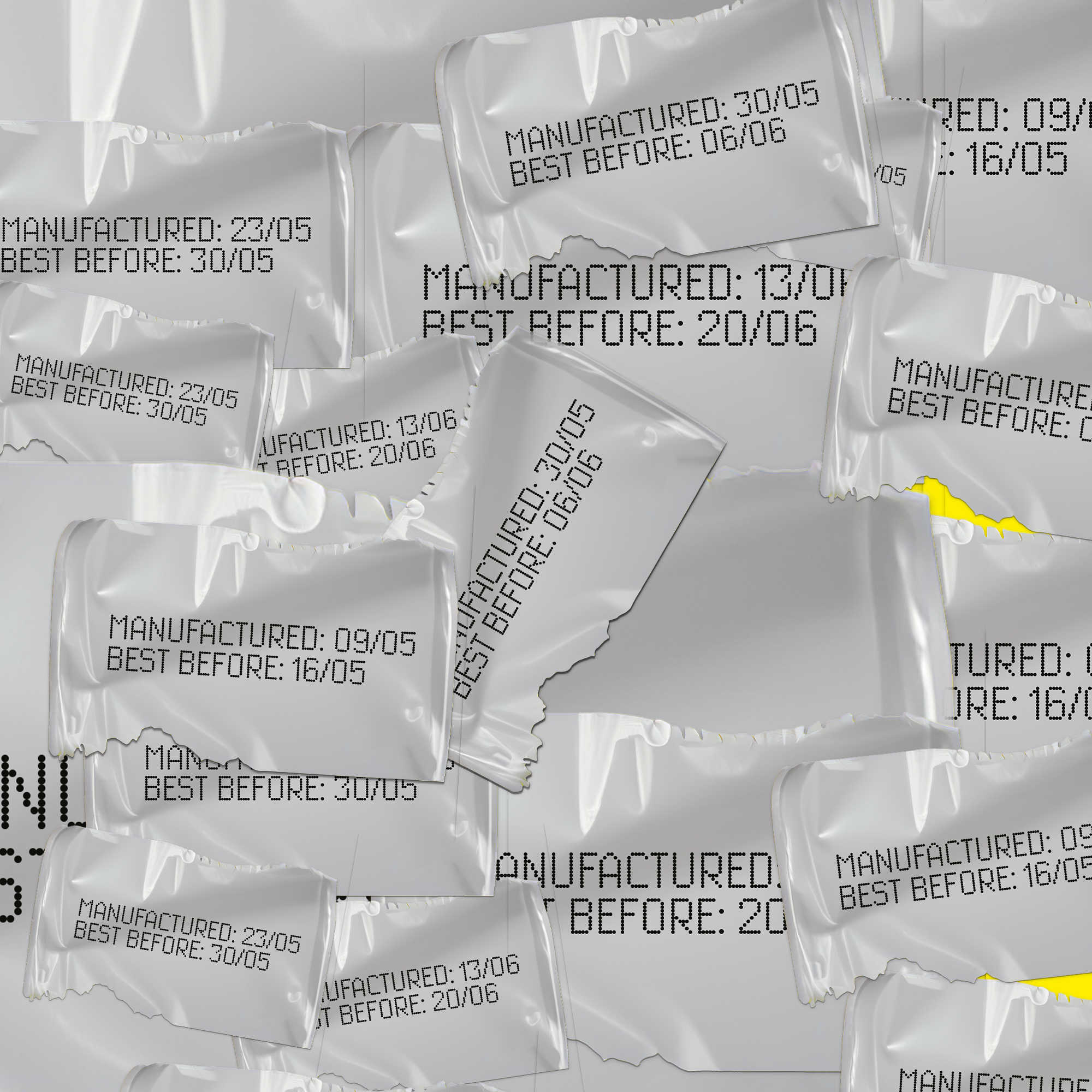

The accepted method for eradicating cane toads is to put them in a plastic bag in your freezer (this is

recognised by experts as the most humane way to kill them). We all grew up wary of small freezer

bags—in case they held a long-forgotten, cryo-euthanised cane toad. To this day, if my little cousins

are feeling particularly virtuous (or adventurous), we end up with mysterious plastic-wrapped lumps

in the freezer.

To this end, cane toad catching has become something of an Aussie sport. Aimed at controlling the

pest, Townsville’s annual “Toad Day Out” is a toad-catching extravaganza, with prizes for largest toad

caught as well as highest number of toads caught. In 2015, participants of the event caught

a collective 143.6kg (317lb) of toads. Townsville also encouraged “ cane toad golf ” in a tourism

campaign, and was promptly reprimanded by the RSPCA for encouraging animal cruelty. To find

a use for all the culled cane toads from toad-busting exercises, entrepreneurs have turned

the notorious amphibian into leather to make novelty purses. We see in gimmicks such as

these the cultural undercurrent of joking around with cane toads. I remember a souvenir shop

in Brisbane selling cane toad plush toys dressed in kilts, and there is an establishment in Port

Douglas called The Iron Bar which is famous for hosting cane toad races at 5.45pm nearly every

day (‘No jockeys, no whips, no steroids, no Dettol, no golf clubs, no bribery’—proclaims the pub’s

website).

Clearly, there is something cheeky and mischievous about how cane toads are represented culturally. A striking example is The Cane Toad Times, an anti-authoritarian satire and humour magazine established in Brisbane in the late 1970s, and revived from 1983-1990. The introduction to the first edition ironically describes ‘”the much maligned, but fascinating amphibian’” as having a ‘”myriad of uses […] from organic cricket to live-action barbecues.’” This edition also includes a satirical section on Elizabeth’s silver jubilee, which aims to revive ‘”all those flagging anti-monarchy sentiments with five pages of unadulterated royalty-roasting’”. In case the flavour of The Cane Toad Times wasn’t clear, we can see from the advertisements that accompany the poems and political cartoons, as well as the ‘What’s On in Brisbane’ section, that the magazine oriented its social critiques around backyard banter and an emphasis on the local. There are advertisements for record shops, independent booksellers, pregnancy testing centres, and local radio stations. The cane toad mutates into an endearingly repulsive rallying symbol for some of our ‘“Aussie battler’”, underdog spirit: anti-monarchy, pro-birth control, supporting home grown culture, and celebrating the peculiarity of Queensland.

Phenomena such as The Cane Toad Times iterate that the toad has come to have a sort of

counter-culture, punk-adjacent roughness to it. Not confined to country narratives of small

towns with ToadMusters, or as an ecological case study in universities—the cane toad’s

spread as iconography has been almost as ubiquitous and unruly as the spread of the species

itself. One of Australia’s highest-grossing) documentaries is Cane Toads: An

Unnatural History (1988), a cult classic often used in school biology classes to tell the disastrous

story of the toad spread. The film was nominated for a Best Short Film BAFTA, showing

the grip that cane toad spoofery has on the Aussie psyche.

Now, it was not the cultural phenomenon of An Unnatural History, but my sister and our neighbour

made a home video about the Cane Toad Problem for a school project. They used a toad-

shaped ceramic garden ornament as a proxy toad, zooming in for close ups with our family’s

chunky 2000s digital camera. My sister and our neighbour put on school lab coats and acted as

scientists trying to stop the toad spread—the film ended with the scientists being hopelessly

outsmarted by the toad-statue (voice-acted by my mum, complete with movie-villain

malevolent laugh). An Unnatural History (and my sister’s project) depict cane toads as the

camp and compelling villain that you know should lose, but secretly root for anyway. Almost like Scar

or Ursula, cane toads become the crowd favourite.

*

For my generation, the most famous cane toad was probably Limpy, the protagonist of a series of children’s books by Morris Gleitzman. Limpy and his friends go on a series of hilarious and yucky adventures to try and reconcile cane toads and humans. Toad Rage (2000), Toad Heaven (2001), Toad Away (2003), and Toad Surprise (2008) were stalwart ‘“books for boys’” because of their gross humour, wild adventures, and likeable toads. I remember seeing Gleitzman at the Brisbane Writers’ Festival when I was a kid. He spoke with boundless energy, like we were all in on the same silly joke. He read out revolting excerpts from his books with glee. In the car afterwards, I remember mum saying disapprovingly: “‘cane toads are a serious problem, he shouldn’t be writing books about them as heroes!”’. But it has never been that simple. As Gleitzman says on his website: “‘I love the fact

that the rangers in Kakadu once printed a picture of Limpy on their stubby [beer] holders even as they did battle with the same warty, ecologically-disastrous visitors to the park who can cause the death of a magnificent five metre crocodile just by being swallowed.”’

That cane toads are beloved characters in a children’s series, the subject of a cult documentary, the

punchline of quintessentially Australian joke events, like toad racing and toad golf as well as

an incredibly serious ecological threat, points to the complexity that the warty creatures hold

in our cultural psyche. But Australians have a long tradition of reclaiming the reviled and turning

them into anti-heroes—just look at Ned Kelly’s quasi-mythic reputation. The anti-

authoritarian, violent bushranger has long been held as an embodiment of Australia’s cultural

mythos. Maybe it comes from a cultural obsession with underdog narratives, tall poppy syndrome,

and unlikely heroes, but the cane toad has arisen as a complicated symbol, particularly in

Queensland. Rebounding between an in-joke and an icon, it is hard sometimes to tell whether the

cane toad is reviled or revered.

Words by Charles Pidgeon. Art by Tabitha Underhill