Swiping White

by Chung Kiu Kwok | May 4, 2020

When Pittsburgh-born author Celeste Ng tweeted that she didn’t usually find Asian men attractive because “they remind me of my cousins”, she couldn’t have foreseen that she would be castigated anonymously as “another white-boy-worshipping cunt” and accused of raising the next Elliot Rodger. Ng’s comment may not have been the product of malice, but it fed into a troubling trend. She became the target of an East Asian ethno-nationalist backlash targeted against ‘race traitors’: Asian women whose supposed colonial mentality induced them to partner with white men.

Eleven percent of all interracial marriages in the US are between a white man and an Asian woman, while only four percent are between a white woman and an Asian man. The difference is even more pronounced in online dating. On platforms like Tinder and OkCupid, white men and Asian women easily receive the most matches. In 2014 OkCupid found that users of all races were significantly less likely to start conversations with black women and Asian men, showing little change from the statistics published five years prior. Controlling for other factors, a study at Columbia found that an Asian man would have to earn a staggering $247,000 more per year to become as desirable to a white woman as a man of her own race. A Cardiff University study on perceived facial attractiveness found that Asian women were rated the most attractive compared to white and black women, while Asian men placed last.

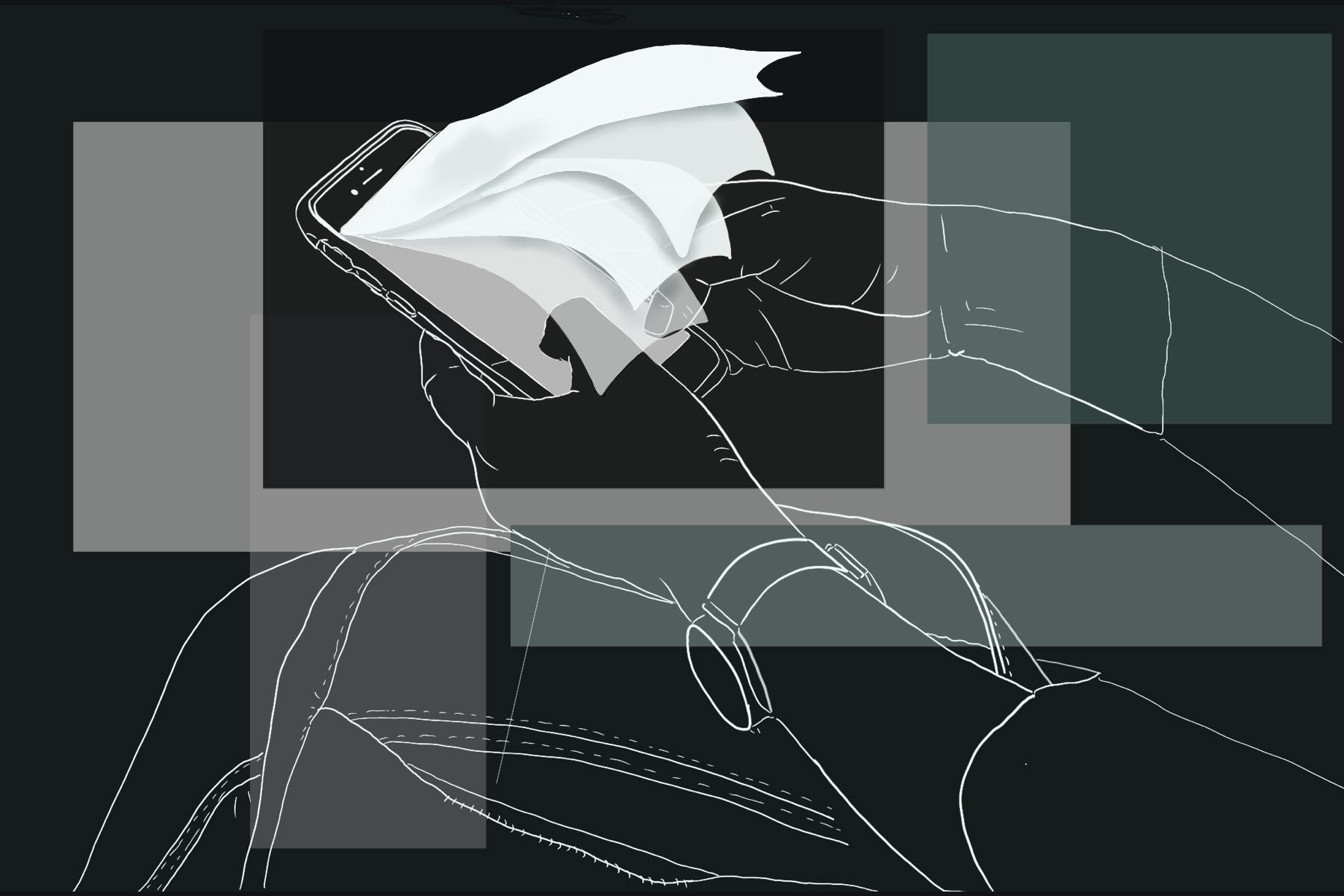

In the US, it is not uncommon for Tinder profiles of white women to include the two little words ‘no Asians’, dashing the hopes of men who otherwise check every one of their boxes. Meanwhile, Asian women are barraged with messages that often betray an uncomfortable fixation on their race.

I’m thinking of eating dinner alone in France a few years ago, and a man coming up close to shout “konichiwa” at me (I’m not Japanese), or my casual date assuming I want to take selfies with him because I’m Asian (I hate selfies). I wonder how much worse the casual reduction of my person to an implied racial trait can become when a man wants to form an emotional connection with me because he believes I am more pliable, more loyal, more mature. Maybe there’s a certain mystique around me because of what I represent: an exotic culture far from home. Maybe I’m supposed to be nerdy – the kind of girl who’s into maths and anime but not politics and therefore won’t bring up pesky opinions in conflict with his own.

Dozens of widely shared articles bemoan the problematic stereotypes behind ‘yellow fever’, a derogatory term signifying the sexual fetishisation of East Asians. In the Western world, they are always the ‘other’. Just under half of all participants in Harvard’s Implicit Association Test automatically associate European Americans with being American and Asian Americans with being foreign, indicating fertile ground for typecasting. Women share their experiences of being hypersexualised and infantilised because of their small bodies and soft voices, as well as the baggage accompanying a history of colonialism and misogyny. Enter an interpretation of ‘yellow fever’ floated by numerous think pieces: men insecure in their masculinity seek out a woman who can make them feel in control, taking the mental shortcut (consciously or not) toward Asian women.

One widely suggested supporting factor is media influence. Until recently, Asian women have been nearly absent from Western politics and popular culture. A recent USC study showed that Asian-Americans represent only one percent of leading roles in Hollywood, compared to six percent of the population. The few instances in which Asian women did appear reinforced the historical façade of an exotic porcelain doll who offers an experience unattainable with the women back home. Madame Butterfly, one of the first famous Western portrayals of an Asian woman, is a fifteen-year-old geisha who waits for her American lover for years after he’s moved on with a wife from home. She eventually attempts (as in the short story) or commits (as in the opera adaptation) suicide when she learns of his betrayal. Nearly a century later she graces the stage in a more palatable incarnation as Vietnamese bargirl Kim from the hit musical Miss Saigon, now seventeen and still the lovelorn ingénue. Actual women of colour were often pushed out of their own stories. Until 1956, the Hays Code governing major studio films in America banned depictions of interracial romance. Anna May Wong, the first Chinese American Hollywood star, was passed over for the female lead of The Good Earth in favour of a white actress.

It’s hardly a surprise, then, that we focus on alt-right and incel men who are unable to attract the attention of ‘emancipated’ women. Prominent Neo-Nazi Andrew Anglin once posted a video featuring his Filipino ‘jailbait girlfriend’, an Internet term referring to a woman who looks young enough that pursuing her would be considered a crime. Despite embracing white supremacy, these men see Asians as a ‘model minority’ – honorary whites worthy of their affections. At the same time, they buy into the submissive yet hypersexual stereotypes dissected above. A number of men undoubtedly fall into this camp, but it does not tell the whole story. Most white men who have a thing for Asian women are not misogynists, fascists, or racists. Most of them may not even crave a power imbalance.

‘Yellow fever’ cannot be examined as a one-sided affair. Critics of the media-based analysis point out that the women who reciprocate problematic advances themselves bear responsibility for their ‘white fever’. In Japan, the term ‘gaijin hunter’ ridicules a woman who intentionally seeks out white men as companions, often with the implication that she is a gold digger pursuing a romantic relationship. Some white men who exclusively date Asian women acknowledge that they do so because Asian women have lower standards for them.

The literature on white-preferring racism in East Asian countries is nowhere near as extensive as that concerning the US or UK. It is so entrenched in society as to go unquestioned; too much a fact of life to merit academic study. Take the case of Sarah Moran, a writer hired as an English teacher in Hong Kong without experience on the condition that she never reveal her mixed heritage. A year later, it comes out that Moran is half Filipina. One of her students pulls out. Wander through shopping malls from Delhi to Tokyo and you will find that the vast majority of ads depict models who are white or conform to white beauty standards: tall, light skin, large round eyes with double eyelids. In former British colonies, where English is the language of elites, Received Pronunciation is a status symbol. Any untrained listener can hear the difference between the speaker who learned their English at boarding school and the one who picked up their fresh-off-the-boat accent from local tutoring centres and YouTube. The ultimate badge of respectability is a degree from the West, ideally Oxbridge or Ivy League. All too often, whiteness confers prestige, and prestige confers desirability.

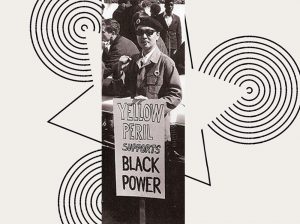

Although dating is treated as a wholly private choice, it does no good to remain blind to the structural forces at work behind who we find attractive. The naked declaration ‘no Asians’ bears a disquieting resemblance to the ‘WHITES ONLY’ signs ubiquitous on Jim Crow storefronts. Even now, some of libertarian, right-wing, or merely racist persuasions argue that private businesses should be allowed to limit service to whomever they please, ignoring that such permissiveness primarily enables systemic prejudice. A restaurant refusing to serve black people reinforces a structural injustice that permeates every area of life; a white woman (or worse yet, an Asian woman) refusing to date Asian men surely does the same. Doesn’t it?

‘It’s okay to have a type’: a refrain commonly heard in our sex-positive feminist community. But if attraction is a kind of magic, it’s a potion whose main ingredients include subconscious value judgments we are fed from childhood. Recognising this is crucial to confronting the very real legacy of racism that underpins seemingly innocuous dating trends.

Will Tinder one day be urged to implement affirmative action into its rating system? I doubt that such a proposal will ever be taken seriously. We remain fiercely protective of our sexual and romantic choices, which are viewed as amongst the most sacrosanct of the private sphere. Dating preferences don’t change at will and taking responsibility for the ways in which mainstream perceptions fail both Asian men and women, as well as men and women of other minorities, is far from a straightforward task. Not every relationship between an East Asian woman and a white man is toxic. In fact, some studies have found them to be amongst the marriages with the lowest divorce rates and highest educational attainments. Of course, this raises the possibility that the trope of the white guy in tech with an Asian girlfriend is not a point of shame, and that what needs to change is the inferior position which Asian men face in the perceptions of peers of all races.

Asian American writers, activists, and public figures have begun pushing back against damaging notions of Asian attractiveness with a frank and often uncomfortable dialogue that acknowledges troubling biases without succumbing to vitriol. They debate the deleterious effects of applying Western standards of masculinity to Asian men, conventionally fictionalised as effeminate or nerdy in ways incompatible with the character of the romantic hero. They praise Crazy Rich Asians, the first major Hollywood studio film to feature a majority cast of Asian descent in 25 years, for representing a desirable Asian hero while calling out producers for casting a biracial actor to do so. Dialogue alone won’t balance swiping statistics, but it is a step towards reclaiming an identity that has been tainted as much as that of the Asian woman.

Nevertheless, the entrenched prestige of whiteness manifests itself much more explicitly in Asian societies than it does in progressive Western ones, and faces higher barriers in communities less used to confronting social injustice. There are no simple solutions. How do you convince a young mother who’s just trying to get the best education for her daughter that the Chinese-looking Londoner will teach English as well as a white-passing peer? Through this lens, the biggest issue with ‘yellow fever’ may not be incels or neo-Nazis, but the ingrained attitudes of societies which need to find a way to pursue what’s admirable about the West without elevating whiteness itself.∎

Words by Chung Kiu Kwok. Art by Sasha LaCômbe.

![[Not-So] Subtle Asian Traits art](https://isismagazine.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/art-300x200.jpg)