The Politics of Space in Oxford

by Jade Spencer | September 27, 2019

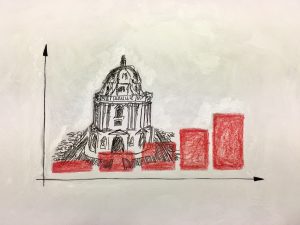

It is perhaps not a surprising statistic – Oxford is the UK’s most expensive city to live in, with an acute lack of affordable and social housing. Over thirty people have died sleeping rough on its streets over the past five years. And the social and economic inequalities in the city are more than uncomfortable: a man from the Northfield Brook area dies, on average, fifteen years before his wealthier counterpart in middle-class Summertown. This gulf in quality of life begins at a young age, with one in four children in Oxford growing up in poverty. Yet the most shocking contrast to all this poverty is rarely commented upon: this is a city where a single institution, the University, has a combined wealth of £9 billion.

Symbols of this disparity are everywhere. As one local activist, Lucy Warin, puts it “there are not many other places where you’ve got one very wealthy entity dominating the centre of a town in such a way”. Walk past St. Giles’ Church hall on a Sunday, and you’ll see that every afternoon it is used as a centre for the city’s homeless and vulnerably housed. In the evenings, the same space is then cleared out for Port and Policy – where future Tory politicians don their black tie to drink and debate. Locals argue over rumours concerning the University’s riches: is it Cambridge, Southampton, or even Lands End, that you can reach while walking only on land owned by an Oxford College? Regardless of the truth, to anyone that has lived, worked, or grown up in Oxford, it is clear that the economic relationship between Town and Gown is not as easy as the University would like outsiders to believe. There is clearly a resentment towards the “complete chokehold” (as Warin describes it) held by the University over the city, in terms of land and property ownership.

In fact, just this week it was revealed that a company wholly owned by St. John’s College have manipulated a loophole in national planning regulations, allowing them to build half the number of affordable homes than is legal on land in north Oxford. As Unviable notes, several developers in Oxford have used this escape clause in recent years to argue that they cannot build the mandatory level of 50% affordable housing, and it can be easily used by colleges like John’s to renege on their responsibility to respond to the housing crisis. Whilst local families on the council’s housing waiting list are placed as far away as Birmingham, the University’s richest college has chosen to inflate its £500 million endowment, instead of providing them with a home.

In its ‘Strategic Plan’ for 2018-2023, the University makes the case that its existence is only an asset to Oxford residents, providing them with world-class hospitals and museums, and outreach programs for local schools. Like many locals, I remain surprised that the institution appears so self-satisfied for essentially fulfilling its basic role as a place of higher education. When I contacted the Oxford University Local Government and Community Relations officer, he told me that the University is “willing to play its role in solving the problems in the city” as an “proactive and valued member of the community.” He was keen to dispel myths of the University as being seen as separate from the City, and cited students’ engagement with the homelessness crisis through voluntary projects as part of this. After five homeless people died on the streets this winter, the Universities’ Director of Public Affairs will now sit on the Oxford Homeless Movement’s steering group. But whilst the University appears keen to advocate for its role as an asset to the local community, this commitment does not go so far as examining its relationship with larger structures that perpetuate city-wide inequality.

Who owns the space?

This inequality manifests itself most clearly through the politics of space: who owns and controls the limited space available in the city, and why? Who has access to these spaces? These questions seemed to be, in part, behind the opening of Oxford Open House last year. Run by Lucy Warin, it provides a free, comfortable, public space for anyone, for as long as they want. Open House has become a hub in the city for discussions and debate around housing, and a vital resource for homeless and vulnerably housed people. When we meet, Warin tells me about a group of women who have experienced homelessness; they use Open House to meet with each other every month, and their experiences and suggestions are fed back to the local council. She tells me “anyone that owns or rents in Oxford is part of the same system which is making people sleep rough”, and therefore a space to talk about this ‘system’ is a vital tool in raising local people’s consciousness on this issue.

The problems faced in Oxford, of course, are not unique: the same story plays across the country. It is the inevitable result of the fatal combination of decades of privatisation, deregulation and austerity. The national housing crisis – an acute shortage of affordable homes and social housing – had its roots in Thatcher’s Right To Buy policy of 1979. As John Boughton writes in his Book ‘Municipal Dreams’, the Grenfell Tower Fire in 2017 exposed the harsh reality of neoliberal policies: “deregulation, public services decimated, their underlying ethos battered, public investment slashed and scorned, ruthless economising that saves pennies and not lives.” Tragedies like Grenfell, and the daily miseries of those who are homeless or inadequately housed, reveal the extent to which the right to safe and adequate housing has been marginalised.

The situation in Oxford is representative of these wider currents at play in the country, but the severity of the housing crisis and social inequality is unique to such a small city. When I chat with Craig Simmons and Dick Wolff, Oxford’s only two Green Councillors, they are both clearly concerned by what Wolff terms the “remorseless tide of growth”, encouraged by Oxford council. It is this remorselness which encourages expansion of the University, and the building of commercial premises like the recently-built Westgate Centre, without any view to their sustainability. Nor does this tide consider whether adequate housing will also be provided to keep up with the growth. As Simmons (now Mayor of Oxford) emphasises, this growth is often developer-led, and Wolff summarises this attitude as: ‘You either grow or you die!”. There is clearly a difficult relationship between local residents who do appreciate the jobs and investment the University brings to the city: “a lot of people, of course, appreciate it; but actually resent the way it [the University] throws its weight around” because of this monopoly”.

New horizons for gentrification

Danny Dorling is the Harold Mackinder Professor of Human Geography at the University, and has devoted his academic career to studying social divisions and rising inequality. Dorling grew up in Oxford, going to a local comprehensive before leaving in the eighties to go to University. He was shocked by the levels of inequality in the Oxford he returned to, and has vocally criticised the lack of responsibility taken by the University for the housing crisis, when it is “more culpable than any other actor for the city’s notoriously high property prices.” We go for a drive; in Blackbird Leys, an estate in south Oxford, he shows me back-gardens where the owners have built large sheds to be rented, illegally, at prices which people on low incomes can just about afford. The Council have started flying drones over the area to police the construction of these sub-lets. Dorling explains how even this area, once known for high levels of crime and poverty, has now become so heavily gentrified that associate professors coming to the city would struggle to live here. In Marston, he shows me a large caravan park, housing people looking for an alternative to the expensive rental market. On the same trip we pass the gated mansions of Haberton Mead, where a five-bedroom home will set you back more than £2 million; this kind of expenditure exists while on the other side of the city, in Rose Hill, almost half of children grow up beneath the poverty line. As Warin points out to me in a later conversation, gentrification in Oxford has gone beyond the level of people being ‘pushed out’ to the borders as is the case in larger cities; the status quo in 2019 keeps the poor out of Oxford completely.

Of course, not all can be blamed on the University. Decades of austerity have also played their role. To take one recent example: the implementation of Universal Credit (the brainchild of Ian Duncan-Smith under Cameron’s government). Since being rolled out in Oxford in 2016, the local branch of the charity Citizens’ Advice (CA) has seen the number of cases they deal with increase significantly. Its Director, Al Bell, tells me how the new system, by making payments to households instead of individuals, penalises victims of domestic violence or financial abuse. The government has often made delays in payments to claimants – one resident who sought help from Oxford CA had not been able to pay their rent for nine months. This is something Caroline Crawford, who works in Oxford for the housing charity Shelter, also picks up on: Universal credit disproportionately affects Oxford residents, where a larger number of people rely on the private rented sector for housing due to astronomical house prices, but are sometimes forced to wait months for payments to help them with their rent.

What can be done?

Yet in this current climate, the University, an immensely wealthy institution – could be doing much much more. St Johns, the college that famously cannot afford to build an adequate number of affordable homes on their land in North Oxford, owns more than £198 million worth of property across the country. It is certain that at least some of this is already in the city itself – Queen’s college, for example, owns more than 30 properties in the city alone. It’s not much of a leap to imagine how much the colleges collectively own across the country, as well as the extent to which they must dominate land and property ownership in and around Oxford. As Dorling tells me: ‘this is a stunted city’, with the Universities’ historic role in buying up land and encouraging the development of an ‘incredibly tightly-drawn’ green belt, preventing a growth in housing stock which would make Oxford a more affordable place to live. The provision of social and affordable housing needed to accommodate the low-paid and migrant workers who prop up Oxford economy is virtually non-existent. In 2016, there were 2116 households on the council housing waiting list, yet only 60 new homes were built by housing associations or the council. The University has the wealth, resources and crucially, the land, to relieve this pressure. Moreover, despite the University (as well as Brookes) agreeing to build more housing blocks for students in order to relieve the pressure on the private rented sector as both universities grow, this commitment only goes a very small way to solving Oxford’s housing woes.

All of these issues feed into the homelessness crisis: there has been a 175% increase in rough sleeping since 2012 in the city. Anyone who has lived in Oxford since before the coalition government has felt this very visible rise. As Warin tells me: “that bottom 10% of the private rented sector has disappeared – people who are evicted, leaving prisons, breaking up with partners… they are suddenly looking at a cliff edge – they shouldn’t be facing hostels and homeless shelters; they just need a fucking home.” This is a point Caroline Crawford reiterates. Shelter sees people on the streets now, who would have never slipped through the net ten years ago. Living conditions have rapidly worsened for the very poorest in society, and Crawford is sceptical about short term solutions currently offered: “If we as a society think that the most vulnerable people need help, then what are we investing in doing that? A bed for one night isn’t going to do that.” This was something that Sharron Maasz reiterated in an interview filmed before her death in January 2019. Sharron was trying to get clean, rebuild her life and in the future wanted to work with people like her who had been made homeless. She was also dictating the words for a book about her experiences. Sharron, like many people made homeless, was a struggling single parent, and had been a victim of domestic violence. She also faced addiction issues, but knew that until she had a stable place to live it would be too difficult to access the support she needed: “I can’t change anything until I get permanent accommodation.”

There are a lot of people in Oxford trying to change the situation. Charities across the city, including Aspire, The Gatehouse, The Porch and Homes4All, are crucial in helping the cities homeless and vulnerably housed (and appreciate committed student volunteers). As well as Open House, Warin is involved in the running of Makespace Oxford – a hub for local charities and social enterprises, providing affordable workspace in the city to those who need it. When I visit Makespace, I was stunned by the array of organisations calling it home: ethical hackers, a young women’s music group, artists, potters, coffee-makers and the library of things, to name a few. Makespace gives these organisations and individuals ‘the ability to fail’ – encouraging innovation and flexibility in a climate ‘strangling’ risky or interesting projects. In a strange (if unsurprising) twist of fate, Oxford Colleges own both the buildings housing Makespace and Open House; they were previously unused and awaiting development, so they are leased out for free under ‘Meanwhile use’ leases. Whilst she is thankful for the space, Warin knows that it’s still not enough to solve Oxford’s housing and homelessness crisis: “If Oxford University made a rent cap, you’ve almost solved the homeless problem in Oxford because they push rents up so much. I can’t believe people aren’t more outraged by their lack of engagement”. Structural inequality in the ownership and use of land, and property, have all played their part in the crisis the city is now in. But in the short-term, nothing can change until the city’s wealthiest institution decides to play fair.

Abridged comment from the Universities’ Local Government and Community relations officer:

The University understands the challenges of living in Oxford and this is why we are working to address the availability and affordability of staff accommodation. The Strategic Plan sets out a commitment for the University’s development to be sustainable, a key part of which will be to ensure those learning and working here are adequately housed. We are also supporting efforts to build more homes in Oxfordshire at the national level. The University is strongly behind the Oxford – Cambridge Arc initiative, which will deliver new and affordable housing and see improvements to regional transport through the East West Rail project. This will help relieve some of the pressure on the city’s property market by offering a wider range of housing opportunities… The University cannot comment on individual colleges’ property portfolios. However, we do work closely with the colleges on the development of our respective estates and they will play an important part in our collective efforts to deliver the housing programme outlined in the Strategic Plan.∎

Words by Jade Spencer. Photographs by Daisy Lynch.